Lockdown has given fresh impetus to calls for the return of treasures pillaged from countries by colonialists, according to author Dan Hicks.

The professor of archaeology and author of The Brutish Museums argues for the restitution of African artefacts from collections in America and Europe, including Scotland. “In the UK, you’re never much more than 150 miles away from a looted African object, and I think that is the way we can turn this into a truly national dialogue,” said Hicks.

“Until now it has largely been a private conversation in the heritage and museums world, but it’s important it evolves into a public conversation. The world has changed around us over the past five years.”

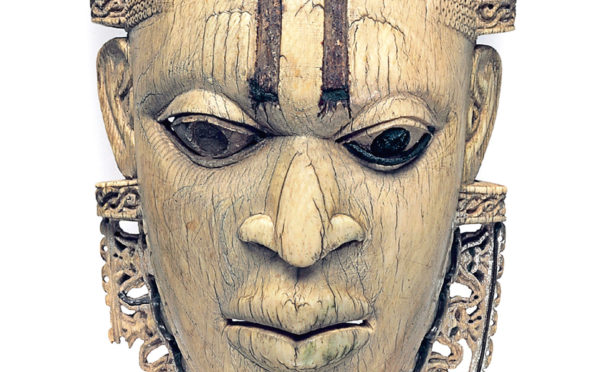

His book concentrates on the Benin Bronzes, a collection of thousands of brass plaques and carved ivory tusks looted from the Nigerian city in 1897 during a British naval attack and then distributed to museums and private collections. Hicks lists 45 museums around the UK thought to have Benin Bronzes in their possession, including the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh and museums in Glasgow but he believes the total is even higher.

“Lockdown has seen a really interesting shift of frame. When we shut the doors, it made us think not just about what’s on display but what is in the stores, because the whole museum becomes a store when the doors are shut.

“Less than 1% of African objects taken under the Empire in the UK are on display, and of the other 99% a lot isn’t on the database. How can we justify holding on to them when we don’t even know what we have?

“This old idea of restitution work being an attack on museums, of emptying the galleries, is absolutely wrong. I’m a curator and I love my museum, and I see this in the same terms we already have for the Holocaust and for human remains, where there are long-established restitution plans. There is no logical reason why the same processes can’t happen for African cultural heritage.”

Hicks is a professor at Oxford University and curator at the institution’s Pitt Rivers Museum. He said his own turning point was the decolonisation campaign by some of the university’s students in 2016.

“I saw a tweet saying the museum was one of the most violent spaces in Oxford,” he said. “Thinking about that, talking to the people who were protesting, what I learned was that, for some of our visitors, walking into the museum and seeing the items on display, even with the story of the attack told ‘well’, they felt it was a violent, traumatic thing to see.”

He added: “If we address the issue we can make our museums fit for the 21st Century. I want to imagine a museum where nothing is stolen and, when people ask for something back, we take it seriously and go through a process that is open to making those returns happen. The museums model is evolving into something more community-led.

“That’s really exciting for museums and is a chance to do what they do best, which is to care for people more than objects, to care for the human stories.

“The idea of simply holding on to objects and hiding them away in a store seems absolutely outdated.”

National Museums Scotland said: “We are committed to revealing and sharing the full range of stories about imperial and colonial activities associated with our collections. In our galleries, we are making changes to displays and labels to address historical bias.

“We are researching collections to ensure our interpretation of these histories and their legacies is based in rigorous and up-to-date knowledge. We are consulting and collaborating with those communities for whom our objects have special relevance. Our policy is to review any request to return items on a case-by-case basis. However, currently we have no outstanding requests.”

The Brutish Museums is out now from Pluto Press

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe