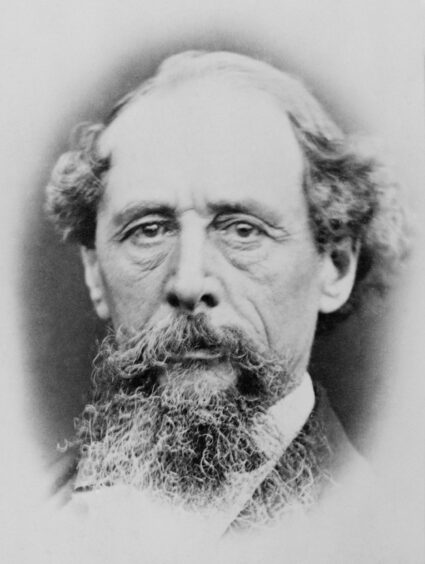

His classic novels may feature some of the most sinister characters in literature but it was travelling through one of Scotland’s most beautiful and desolate glens that gave Charles Dickens the heebie-jeebies.

The acclaimed author was best known for chronicling London life in enduring classics like A Tale Of Two Cities and Oliver Twist but after becoming a best-seller he travelled to visit the marvels of the world, ancient and modern.

His touring often brought him north but, in Glencoe, he stumbled upon a place he would not rush to revisit and a new book, collecting his travel writing, reveals how he was gripped by both eeriness and awe.

He wrote: “The pass is an awful place. It is shut in on each side by enormous rocks from which great torrents come rushing down in all directions. In amongst these rocks on one side of the pass (the left as we came) there are scores of glens, high up, which form such haunts as you might imagine yourself wandering in, in the very height and madness of a fever.

“They will live in my dreams for years – I was going to say as long as I live, and I seriously think so. The very recollection of them makes me shudder.”

Born into a working-class family and struggling alone on the streets of London in his early life, Dickens could only aspire to the travels wealthy young men in that era undertook as a rite of passage known as the Grand Tour.

When he found himself making money from his writing, however, he decided to take himself and his family on their own mini versions, penning his thoughts on destinations from Scotland to Rome, Paris and New York.

Author Lucinda Hawksley was perfectly placed to compile the collection of his work, having been a travel writer herself and a direct descendant – she is Dickens’ great-great-great-granddaughter.

“It has been amazing to discover not only how much Dickens was inspired by the world but how much the world has remained inspired by him,” she said. “Everyone thinks of him as a London author and he had such a love/hate relationship with the place but he wasn’t born there, nor did he die there.

“He’s so firmly associated with it, which is really intriguing because most of his novels centre around London but in his personal life he was often writing from other places across the world.

“Seeing the world was one of his ambitions. He’d never been able to do a Grand Tour because he was working-class, so he decided he was going to travel as much as he could.”

A chapter of the book focuses on Dickens’ visits to Scotland. His wife, Catherine Hogarth, was the daughter of Sir Walter Scott’s legal adviser and spent most of her childhood north of the border.

Dickens, who referred to his children as half-Scottish, first travelled to Edinburgh in 1834 as a journalist for The Morning Chronicle and his experience of the city inspired an episode in The Pickwick Papers – the melodramatic ghost tale, The Story Of The Bagman’s Uncle. The poverty on the streets he saw also inspired parts of A Christmas Carol.

He would return to his wife’s birthplace in 1841 but this time as a well-known writer who was being awarded the Freedom of the City.

“Catherine was in her teens when they left so she wanted to go back,” said Hawksley. “She also loved the food of Scotland and their kitchen was full of Scottish cuisine.

“Travelling up to Edinburgh in 1841 was a dream and they went on a fantastic trip around Scotland with their friend Angus Fletcher, an interesting chap who was a sculptor from the Highlands.

“When they visited the Adelphi Theatre, the band struck up the song Charlie Is My Darling. People were really welcoming to them.”

Glencoe was also among the destinations on the trip. Hawksley herself visited before reading her ancestor’s letters back south to friend and eventual biographer John Forster about what he called a “perfectly terrible…awful place”.

She said: “I was really struck by just how much atmosphere there is there and how frightening it is. And that’s really what Dickens is getting across. He did exactly the same with the Colosseum in Rome. He was really affected by atmosphere and the idea of the supernatural. He hated the Colosseum and yet was drawn to it every day he walked past it when he was in Rome. It’s a similar feeling he had about Glencoe, that there’s been so much death there and you can almost feel the cries of agony.

“Obviously, he would have known about the history of Glencoe but it struck him in a very visceral way.”

There is also a tale of Dickens’ carriage getting caught in a flood near Dalmally. They escaped, but the driver and horses were in jeopardy until the arrival of a “wild Highlander in a great plaid”.

“It was the landlord of their inn,” said Hawksley. “He just went in and helped them get the carriage out of the flood. Dickens was really impressed by the bravery and the stoicism behind Highlanders – though he wasn’t impressed with their sanitary habits. Most people knew about the Highlands of Walter Scott. Hearing about the day-to-day living and how they travelled around, it was such a different way of life compared to those in the south.”

Hawksley’s research into her ancestor has helped her gain a greater sense of the man he was, and elements of his character she had previously been unaware of. This includes his great bravery, from having to become street smart in a dangerous London to the precarious encounters on his travels.

As a child, when his parents were in debtors’ prison, he was living by himself, skirting the most dangerous slums in what was the biggest city in the world. “The reports of violence are shocking,” Hawksley said. “People used to wear spiked collars under their cravat because people would try to strangle you on your way home. London was a very dangerous city when the 12-year-old Dickens was living there on his own.”

She also found letters from his trip to Italy, where he described the areas he and French guide Louis Roche were travelling through as bandit country.

“He writes at one point how he wished he had a pair of pistols because it’s so dangerous, and a constant fear of being robbed when they’re travelling around,” she said.

“The first trip on a steamship, too, sounds absolutely terrifying. Dickens writes home and says that never again would he trust himself and his wife to a steamship, because it’s so frightening.

“It’s either far too heavily laden with coal at the beginning, or frighteningly unladen at the end. He also talks about the fact the chimneys belching out fire are so unstable that if you got caught in a storm, and they were knocked over, the whole ship would go up in flames.

“All these Victorian travellers were so brave. Today, no matter how much we think we’re intrepid, it’s nothing compared to putting yourself in these terrifying vessels and heading out to places unknown.”

Hawksley also found Dickens had a deep admiration for migrants who had packed up their lives in order to find a new start. “He looks at the ships coming in and the people, usually the poorest of the poor, from Britain and Ireland after the famine,” she said.

“He writes about couples who have put their trust in each other and used every bit of money they have to go to somewhere like America, Australia or Canada with no idea what they’re going to find when they get there.”

Scotching the myth behind Edinburgh’s link to Scrooge

As well as detailing Dickens’ work while on his travels, the book debunks a common myth around the origins of A Christmas Carol’s Ebenezer Scrooge.

It has been claimed the author wrote in his diaries that he found the grave of an Ebenezer Lennox Scroggie on an evening walk around Canongate churchyard in Edinburgh.

But, Hawksley found, Dickens destroyed each year’s diary when he was finished with it and the 1841 edition did not survive.

There are no records for Canongate prior to the visit, so Scroggie’s burial cannot be verified.

Claims the gravestone was destroyed by work in the 1930s also cannot be proven as there is no record of it taking place in extensive council minutes.

“When I went to the archives, they said they’re always asked about this and, no, there isn’t any foundation for it,” said Hawksley. “I actually had somebody a few weeks ago at the Dickens Museum come and ask about it. He said he’d seen the gravestone, but it doesn’t exist – unless somebody put up a fake one!”

From Paris to Pompeii: How Dickens and his family viewed the world on their own Grand Tour

Many of the travels Dickens undertook can be viewed in the light of a Grand Tour: the journey wealthy young men of the 18th and 19th Centuries took to round off their education.

This was something the Dickens family could never have afforded but to which the author had long aspired. When he became financially secure through writing, Dickens took himself and his family on his own version and wrote about what he saw.

On Wall Street, New York

Many a rapid fortune has been made in this street, and many a no less rapid ruin. Some of these very merchants whom you see hanging about here now, have locked up money in their strong-boxes, like the man in the Arabian Nights, and opening them again, have found but withered leaves.

On Niagara Falls

We went up to the rapids above the Horse-shoe – say two miles from it – and through the great cloud of spray. Everything in the magnificent valley – buildings, forest, high banks, air, water, everything – was made of rainbow. Turner’s most imaginative drawing in his finest day has nothing in it so ethereal, so gorgeous in fancy, so celestial. We said to one another (Dolby and I), “Let it for evermore remain so,” and shut our eyes and came away.

On Pompeii

Stand at the bottom of the great market-place of Pompeii, and look up the silent streets, through the ruined temples of Jupiter and Isis, over the broken houses with their inmost sanctuaries open to the day, away to Mount Vesuvius, bright and snowy in the peaceful distance; and lose all count of time, and heed of other things, in the strange and melancholy sensation of seeing the Destroyed and the Destroyer making this quiet picture in the sun.

On Lausanne, Switzerland

There are all manner of walks, vineyards, green lanes, cornfields and pastures full of hay. The general neatness is as remarkable as in England. There are no priests or monks in the streets, and the people appear to be industrious and thriving. French (and very intelligible and pleasant French) seems to be the universal language. I never saw so many booksellers’ shops crammed within the same space, as in the steep up-and-down streets of Lausanne.

On Paris

I cannot tell you what an immense impression Paris made upon me. It is the most extraordinary place in the world. I was not prepared for, and really could not have believed in, its perfectly distinct and separate character. My eyes ached and my head grew giddy, as novelty, novelty, novelty; nothing but strange and striking things; came swarming before me. I cannot conceive any place so perfectly and wonderfully expressive of its own character; its secret character no less than that which is on its surface; as Paris is.

On the Colosseum, Rome

It is the most impressive, the most stately, the most solemn, grand, majestic, mournful sight, conceivable. Never, in its bloodiest prime, can the sight of the gigantic Coliseum, full and running over with the lustiest life, have moved one’s heart, as it must move all who look upon it now, a ruin. GOD be thanked: a ruin!

Dickens & Travel: The Start Of Modern Travel Writing by Lucinda Hawksley is published by Pen and Sword and is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe