For the British sports fan sitting in their living rooms devouring the beginnings of blanket television commentary in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, the names roll off the tongue.

In cricket, the undisputed king of the spoken word was John Arlott, in golf it was Peter Alliss and in tennis it had to be Dan Maskell.

Peter O’Sullevan was the silky voice of horse racing, Murray Walker was your Formula One man, Harry Carpenter was boxing’s champion and Eddie Waring’s up-and-unders helped popularise Rugby League.

And in the other oval ball code, there was only one voice of rugby.

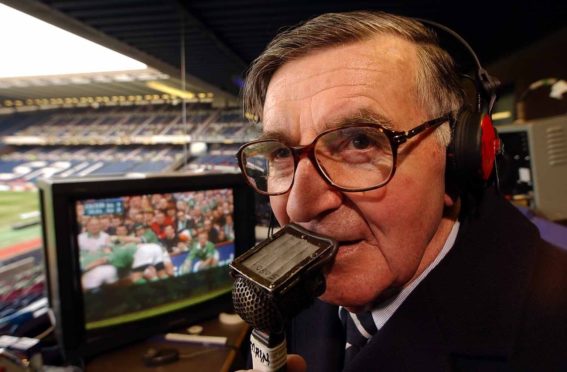

Bill McLaren may have been gently lampooned for his most famous phrase – “They’ll be dancing in the streets of (insert the name of any random town) tonight” – but the Scot from Hawick was perhaps the most widely respected commentator in any sport during almost five decades behind a BBC microphone.

His voice is still so familiar that when you watch any international match you can almost still hear his Borders tones despite the fact that Bill passed away nine years ago at the age of 86.

He was never an international rugby player but he might have been.

A talented flanker in his youth, he had been on the verge of a full Scotland cap when he contracted tuberculosis, which almost killed him.

He recalled: “I was desperately ill and fading fast when the specialist asked five of us to be guinea pigs for a new drug called streptomycin.

“Three of the others died but I made what amounted to a miracle recovery.”

McLaren’s first commentary was made while convalescing from TB, describing table tennis matches for the hospital radio.

As a child, he had copied the voices of the rugby commentators he heard on the radio, and wrote fictional accounts of matches which always saw Scotland triumph.

His career progressed rapidly and he made his national debut for BBC radio in 1953, when Scotland were beaten 12-0 by Wales, before switching to television six years later.

The depth of McLaren’s research became legendary. He would spend days watching teams train before a match, and then spend nights practising with his own special packet of cards.

His voice was instantly recognisable, and generations of rugby fans grew up listening to a man they believed to be fair, knowledgeable and a lover of the game.

Among the highlights of his career was the commentary for Scotland’s Grand Slam victory over England at Murrayfield in 1990.

His voice was almost operatic in its clarity and range as he described his son-in-law Alan Lawson scoring against England in 1976, yet still managed to convey the moment without any obvious bias.

He combined his commentating with working as a physical education teacher in his hometown of Hawick, where he had been born in 1923.

By the time he retired from teaching in 1987, he had coached several players who went on to play for Scotland, including Jim Renwick, Colin Deans and Tony Stanger.

He and his wife Bette, whom he had met on a blind date at the town’s hall in 1947, famously used to play 18 holes of golf together every day.

McLaren claimed that every day out of Hawick “was a day wasted”.

After a distinguished career, McLaren retired in 2002. His final commentary was Scotland’s match with Wales, when the crowd sang For He’s A Jolly Good Fellow in his honour.

He became the first non-international rugby player to be inducted into the International Rugby Hall Of Fame, and was made a CBE, OBE and MBE.

As well as the reams of information he imparted to viewers, McLaren had a penchant for word-play, with his metaphors and similes becoming the stuff of legend. He described Scotland scrum-half Roy Laidlaw as being like “a baggy up a Border burn” – a baggy being a small fish that McLaren had learned as a Hawick child was incredibly difficult to catch.

Doddie Weir was “the lamppost of the line-out”, Bill Beaumont was “a man who looks as if he enjoys his food,” stopping Jonah Lomu was “like trying to tackle a snooker table” and of Phil Bennett, “they say if you ever catch him you get to make a wish”.

He compared the ball on wobbly goal-kicks to moving like “three pounds of haggis”, a sidestep to a “shaft of lightning” and reckoned props were “as cunning as a bag of weasels”.

His affability was legendary, but there was also an inner steel to McLaren, developed through the battles of an incredible life story.

The tuberculosis he contracted at 24 was not his first brush with death. During the Second World War he’d survived the Battle of Monte Cassino, the largest land battle in Europe, which he described as his “vision of hell on earth”.

Back home in Hawick after the war he featured in one Scotland trial, but worries about his fitness led him being diagnosed with TB, for which there was no cure at that time.

He spent six months in hospital and then nearly two years in a sanatorium.

He was sustained by Bette – to whom he proposed while in hospital – and as he recovered he began to write for a magazine.

PE teaching was ruled out by the TB and so he took a job as a junior reporter on the Hawick Express.

His editor recommended Bill for a trial audition with the BBC, and by the end of 1952 he was commentating for the Scottish Home Service.

He had married Bette and the couple had two daughters before PE teaching came back onto the agenda in 1959.

There were few rugby players of any note to have emerged from Hawick not to have undergone some McLaren tutelage.

He commentated on the famous moment when his former pupil Stanger scored the match-sealing try against England in the 1990 Grand Slam success.

Above even his rugby, McLaren was a family man.

He always insisted that the BBC book him travel home from European destinations on the night of the game, whenever possible, to ensure he would not be parted from Bette for longer than necessary.

Six months after Bill died, his two grandsons, Rory Lawson and Jim Thompson, were selected to play for Scotland for a game against Argentina.

It would have been Bill’s dream commentary. And maybe the one that might have tested even his neutrality.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe