FROM their first broadcast in 1964, they were the pirates of the airwaves — and they changed the way Britain thought about music.

In those halcyon days, many a youngster felt the BBC were failing in their duty to let us listen to the new favourites, and it was hard to hear the Stones, Kinks, Animals or anyone else on mainstream radio.

So it was that Radio Caroline began her naughty transmissions from the seas — a ship off the coast of Felixstowe, to be precise — and gave us what we desired.

“Twenty-three-year-old Irishman Ronan O’Rahilly picked up on an idea, which had worked off the coasts of Holland and Scandinavia,” say the authors of a new book on the subject, Keith Skues and David Kindred.

“This was to fit a ship as a radio station that could operate outside the British territorial limit of three miles.

“In January, 1964, he met Allan Crawford, a music publisher with plans to launch Britain’s first offshore commercial radio station, Radio Atlanta.”

Ronan had other ideas, and his father owned the Port of Greenore, in Southern Ireland, an ideal spot to fit out a pirate ship of his own — Caroline.

As early as 1934, however, others had been trying this, although no pirate station had lasted long.

By Radio Caroline’s first birthday, though, it had grown so big that it even had its own Caroline Bell Awards, which were presented to some of the biggest names in music.

“Petula Clark won her award for best female recording artist for her version of Downtown,” the authors reveal.

“The Animals received theirs at London Airport, as they left for New York.

“The presentation, made by Ronan O’Rahilly, was for the best group record of the year, House of the Rising Sun. Best male vocal of the year was made to Tom Jones for It’s Not Unusual.”

Tom Jones himself would later say: “Radio Caroline made a hit out of It’s Not Unusual. They played it a long time before the BBC picked up on it. I still have the Radio Caroline award, which is a fine brass bell on a wooden trestle.

“Had Caroline and the other pirate stations not been as adventurous as they were, maybe BBC pop radio may never have seen the light of day.”

With their Dutch crew, quarters spread over three levels, decent food and plenty of records to play, it was a fascinating time for young DJs like up-and-comer Tony Blackburn and the maverick Emperor Rosko, who kept his mynah bird, Alfie, on board.

True, the Government didn’t like it and discussed it in Parliament, and the law was never far behind them in trying to run them out of business, but it did cause a pop revolution in Britain.

Competitiors came and went, of course, with Radio London one of the most notable.

They relied on the good ship Galaxy to keep their DJs one step ahead of the law.

“It was a former United States minesweeper, USS Density, that had served in the Far East in the Second World War,” say the authors.

“As well as all the latest pop tunes, Radio London broadcast news bulletins.”

More and more pirate stations, of every shape and size, popped up — even Screaming Lord Sutch got involved, as did a certain real Lord and his Lady.

Radio Sutch, started by the maverick politician and musician, did its broadcasting from Shivering Sands Army Fort, close to the Thames Estuary.

“The format we had caused eyebrows to be raised,” recalled Sutch wryly. “And because of the enormous depth of my political appeal, the authorities had to silence me!

“I was finally forced to surrender in order to avoid bloodshed. I was satisfied that I had made my point.”

In the summer of 1967, Lord and Lady Arran paid a courtesy visit to Radio London.

“They had lunch on board with disc jockeys and later were interviewed live on air,” say the authors.

“Lord Arran said after his visit: ‘My wife and I had a wonderful day. Pop radio has brought a great deal of joy to many people.’”

The pirates themselves couldn’t have put it any better!

Perhaps unsurprisingly, in the more politically-heated 1970s, pirate radio began to court some real controversy, and played a major part in events in the House of Commons — and even who ruled there.

“Stations were experiencing jamming, carried out by the Ministry of Posts and Telecommunications,” the authors explain.

“Other frequencies were tried, but on each occasion, the jamming continued.”

Despite this, when Caroline was briefly able to be heard, she played a significant role.

“In 1970, during the General Election, many people believe that the propaganda transmitted by Caroline did have an effect on the outcome of the results. These went against Harold Wilson’s Labour government, that had outlawed them in 1967.

“DJs urged listeners to vote for the party that supported commercial radio. On land, a bus with Ronan O’Rahilly and Simon Dee aboard toured key marginal seats.”

In time, the pirates would be run out of business, but they revolutionised music.

For whole generations of groups and fans, we will be forever in their debt because of that.

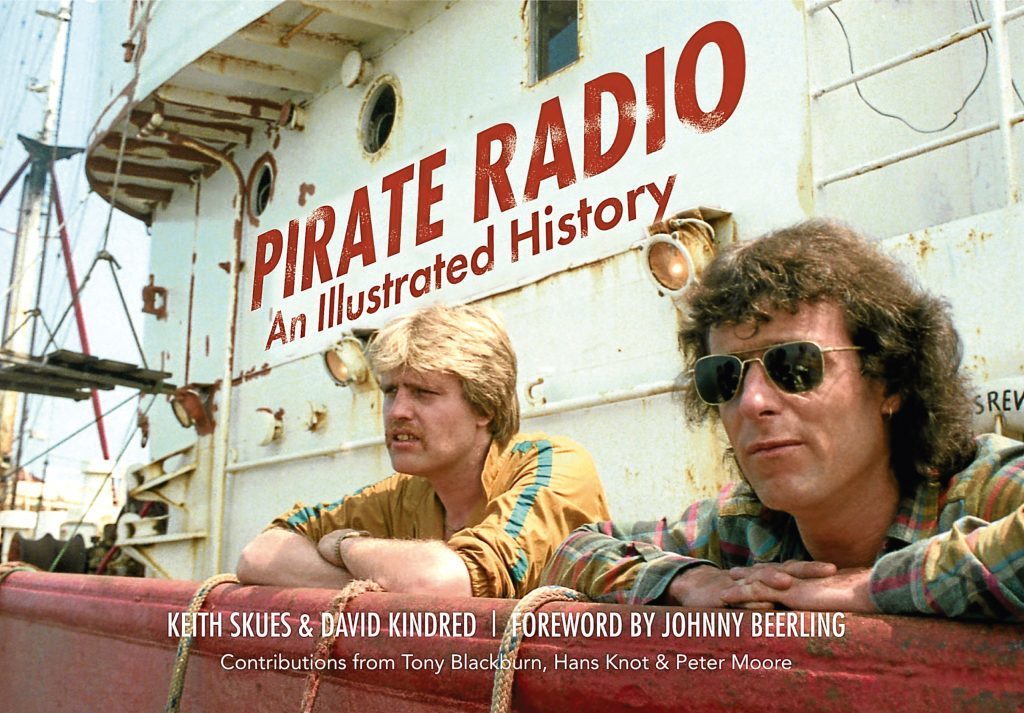

Pirate Radio: An Illustrated History is published by Amberley, ISBN No. 978-1-4456-5905-3, price £17.99.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe