It was a profoundly shocking wave of illness, striking down scores of people for no obvious reason. More than 50 years later, by chance, and genius, it would lead to the Covid vaccine.

It was Edinburgh in 1969 and 11 people would die, seven patients, two transplant surgeons and two laboratory workers in the city which had become Britain’s foremost centre for transplantation and transfusion medicine after Michael Woodruff carried out the UK’s first kidney transplant in 1960.

Yet hepatitis, inflammation of the liver, was killing indiscriminately. It took months for the cause to be established – a small leak in a pressure gauge in a dialysis machine which passed infected blood on to others.

Everything was tightened up after a series of recommendations from an inquiry. The outbreak featured in Colin Douglas’s novel A Houseman’s Tale which was made into a TV drama. And there it might have all ended.

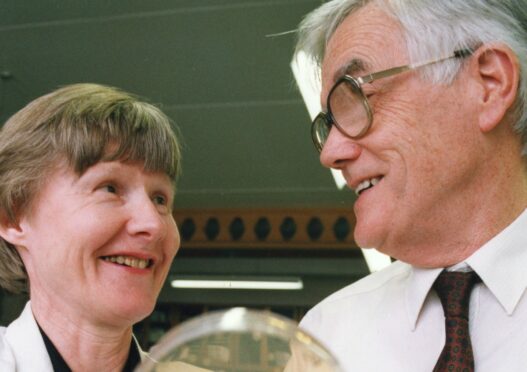

However, across the city, professor Ken Murray and his wife Noreen were starting work in the virtually unknown area of genetic engineering at Edinburgh University’s department of molecular biology.

By 1973 the Murrays had achieved their first major success in making recombinants, or new genetic material. This involved slicing chunks of DNA to put into bacterial cells capable of accepting another gene but still functioning and reproducing.

In effect, they had built and tooled up a factory ready for production. All it needed was the right product. This was the prototype of the process used by the Oxford University team to develop the first Covid-19 vaccine in record time.

Back in February 1978 eight of Europe’s leading scientists in genetic engineering, including Murray and his Swiss colleague Charles Weissman, set up a biotech company, Biogen, to consider practical applications of the technique. Cancer therapies seemed better targets than vaccines, but Murray suggested hepatitis B.

On his return from Switzerland, he approached the research and clinical unit set up after the 1969 outbreak under professor Barry Marmion who gladly provided samples of the live virus. This was essential so that its characteristics could be studied and mimicked by a man-made product.

The first experiment was carried out in June 1978. The technology was so new and frightening that the US banned work on human viruses. The British licensing group insisted that experiments be conducted in the top security conditions of the Porton Down germ welfare establishment.

Murray would work in Edinburgh, fly to Weissman’s lab in Zürich which had key expertise and antigens, then to London and more research at Porton Down. “A lot of people laughed at us and said it was all a daydream, just pie in the sky” he later recalled.

“In November 1978 we got our first results which showed we had succeeded in making hepatitis antigens in the bacterium we were using. There was a lot of rejoicing but after that there was a lot of hard slog.”

As a synthetic vaccine, it was inherently safer than others made from blood products and much cheaper to manufacture.

Drug companies developed the discovery, paying royalties to Biogen on the vaccine and diagnostic kits resulting from the Edinburgh work. These went on to save millions of lives and British innovation was being rewarded.

Royalties started to trickle in – less than $500 in 1984. Within five years this had turned into a flood. It became the million-dollar microbe and ultimately generated more than $100 million before the patents expired.

Murray could have joined the super-rich club. Instead, in 1983 he set up The Darwin Trust which received two thirds of the money, the remainder going to Edinburgh University.

The son of a miner in Wakefield, he didn’t get many early breaks. His dad was injured in a pit accident and became a school janitor in Nottingham – appropriately enough for his son’s later role as Robin Hood.

There was no prospect of young Ken heading off to university. At 16 he joined Boots as a lab assistant. He studied part-time for his first degree, then a PhD at Birmingham University where he met and married fellow scientist Noreen.

“It has been a bit of a fairy tale,” he remarked. “I could have taken the money, but I didn’t need to. I don’t particularly want a Rolls-Royce.”

By 1983 there was a new frightening virus – HIV and the resulting illness, Aids (acquired immune deficiency syndrome). The Darwin Trust played a key role in setting up the Aids immunology unit at Edinburgh and establishing the Scottish Aids Research Appeal.

Alongside every fairy story there are nightmares. Thousands of haemophiliac and other patients were harmed or killed by the import of contaminated blood from the US. This has been described as the worst treatment disaster in the history of the NHS. Only now, after decades of delay, are its consequences coming under scrutiny by the Infected Blood Inquiry, chaired by Sir Brian Langstaff.

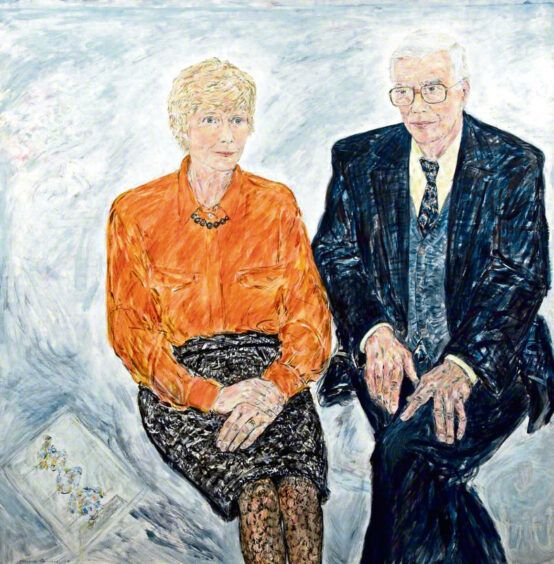

Ken, knighted in 1993, died in 2013 two years after Noreen. They were internationalists recognising that science, like disease, does not recognise national boundaries. In their careers they had worked under double Nobel laureate Fred Sanger in Cambridge and had sabbaticals in Stanford in California and Heidelberg in Germany.

Their legacy continues in the library named after them at Edinburgh University and 500 young molecular biologists from across the world supported by The Darwin Trust to pursue PhDs.

Scientific research is mainly hard graft and careful observation, often hitting disappointment and dead ends. But, as the Murrays demonstrated, long-term investment sprinkled with sparks of courage, luck, and imagination can turn dreams of breakthroughs into reality.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe