It rules our everyday lives, and yet we barely notice it. Without alphabetical order, many routine tasks we undertake would be chaos.

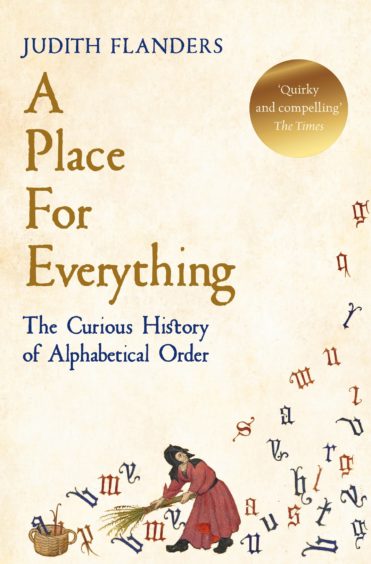

But how did it come to be? Author Judith Flanders tells Sally McDonald the Honest Truth about the curious history of alphabetical order.

Why did you write this book?

It began with a review I read of a book on Wikipedia and online reference works, and it mentioned in passing that encyclopaedias didn’t have to be in alphabetical order any more. It made me wonder about alphabetical order, and I tried to find something to read on the subject, only to discover there was almost nothing. So, I decided it would be a fun project.

How long did it take?

A couple of years. At first I was surprised by how little attention had been paid to the subject. It was as if it was so huge, no one could see it.

What was the earliest use of alphabetical order, and how did it come about?

Until the Middle Ages no one was much interested. We know from a handful of scattered uses that alphabetical order was known, but other sorting methods – chronological, or geographical, or hierarchical (where the most important person comes first, as with the Domesday Book, for example) were much more common.

It’s only in the 13th Century alphabetical order came into regular use, when the development of universities meant there was more importance put on citing your sources. But even after that, it took a long time for alphabetical order to become standard.

So when did we really start thinking alphabetically?

It was the encyclopaedia writers of the 18th Century – Ephraim Chambers’ Cyclopaedia in England, Archibald Constable and Colin Macfarquhar in Edinburgh, with their three-volume Encyclopaedia Britannica, and Diderot and d’Alembert’ Encyclopédie in Paris – who set the fashion.

What was your most surprising research discovery?

In the Middle Ages, lots of things were organised in three, or sevens, to symbolise the Trinity or creation of the world. What blew me away was finding a scientific paper that pointed out that most drugs today are still prescribed for three or seven days, even though there’s plenty of clinical evidence saying that two days, or five or 10, work just as well.

More generally, it was finding out about the dozens of ways people have been organising things. One mediaeval organising system for medical textbooks was “head to heels”, beginning with diseases of the head and working down the body until finally you get to the feet.

What was the most memorable find?

I loved one story about how history was changed by bad organising. In the 1290s Edward I of England tried to claim the overlordship of Scotland. The Scots were not keen, and Edward had to order a search of all the chronicles and registers in monasteries, as well as the Chancery rolls, for historical mentions that would bolster his claim.

These searches failed to turn up anything, and so, apart from the political implications, that failure led to royal archives being reordered – by subject, by category, by use – to ensure it wouldn’t happen again.

Will there ever be a day when we don’t rely, given the rise of computer algorithms and smart phones, on alphabetical order?

As a historian, it’s not my job to speculate about the future. But if we look at Wikipedia today, we see it still uses alphabetical order. When Wikipedia began, it paid a private homage to its predecessors by naming their computer servers after various categories and types of classifier, among them the encyclopaedists of the Middle Ages.

I found it so touching they wanted to honour that millennium-old connection.

A Place For Everything: A Curious History Of Alphabetical Order by Judith Flanders is published by Picador

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Clive Barda

© Clive Barda