As the world’s wealthiest men join the race to space, the dream of humankind finding new homes in the stars is again inching from sci-fi fantasy to reality.

Space agency Nasa has a renewed determination to put humans on the Moon then Mars and its travel plans are founded on an engine invented by a little-known Scot more than 200 years ago.

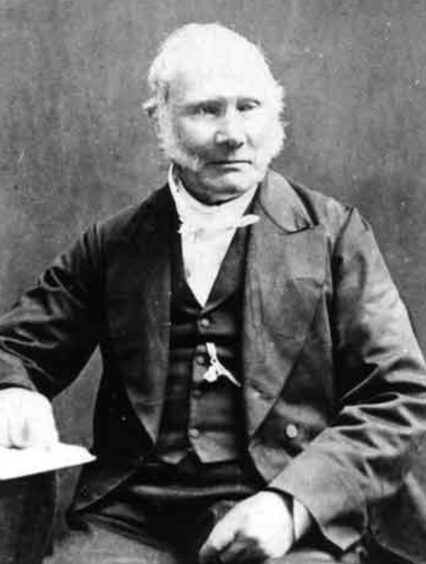

In 1816, the Reverend Robert Stirling patented a design for a revolutionary heat exchange engine and in 2018, Nasa announced they had used his technology in the successful test run of a tiny nuclear reactor that could power their drive for the stars, with profound consequences for the future of mankind.

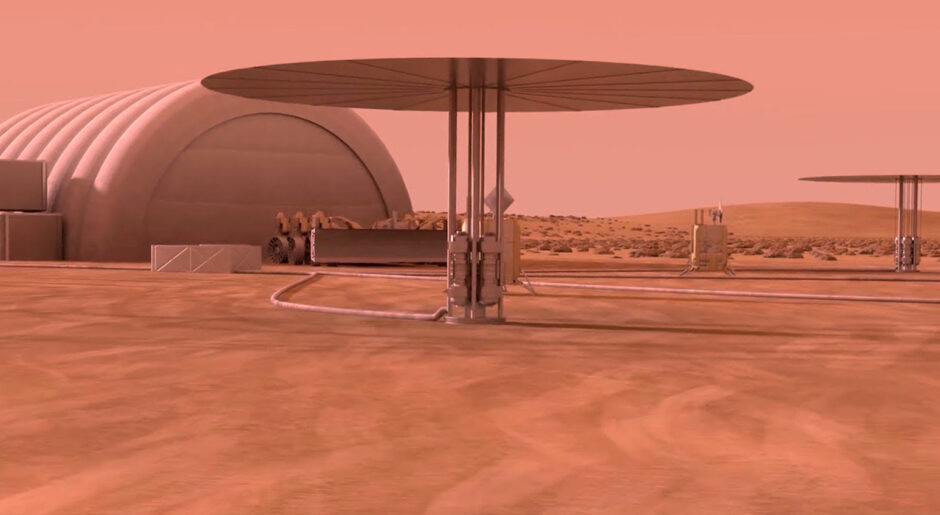

The reactor called Krusty (Kilopower Reactor Using Stirling Technology) would enable them to maintain permanent bases on the Moon, Mars and other planets, for “long-duration” stays.

Although two Stirling engines are held in Scottish museums, author Phillip Hills believes the inventor does not have the prominence he deserves.

Now Hills is putting that right in a book that tells the story behind Nasa’s reactor, beginning with Stirling’s original design.

Speaking from his home in Montrose, Hills said: “It is astonishing that an engine on which humanity’s greatest enterprise depends was invented by a Scotsman more than 200 years ago but hardly anyone knows about him.

“While the engine is well-known to enthusiasts, if you stop people on the street and ask them, you will find they know nothing about it. I have tried. The book is about that engine and about the people – many of them remarkable – who have brought it to the point at which it can be installed on a spaceship and expected to run non-stop, without repairs or maintenance of any sort for tens, perhaps hundreds of years.”

He explained that until Krusty, there were very few sources of power to drive a spaceship once off the ground. Electricity was vital to power propulsion, course changes and systems on board.

“The problem is, how do you achieve propulsion of any sort once you are floating around in space?” he said. “You can carry rockets if you can afford to lift them. There is ion propulsion, but that needs electricity and how do you get it? If you are close to the sun, you can use solar panels. But by the time you get out as far as Jupiter they won’t work because you are too far from the sun.”

Radioisotope power systems that convert heat from the natural radioactive decay of the isotope plutonium-238 into electrical power have been used to operate computers, science instruments and other hardware on board Nasa missions such as the Curiosity rover on Mars.

But Hills said: “P-238 is very nasty stuff. You can get electricity but you get very little and it cohabits with this really hellish radioactive material. So Nasa have put together a small fission reactor, about the size of a dustbin, with eight little Stirling engines. The heat from the reactor goes by means of liquid sodium heat pipes into the Stirling. If you put heat in at one end and take the heat away at the other, you can make it move. It uses a clever linear alternator devised by the late William T Beale in the mid-60s.

“Putting the two together gave the potential for a drive into planetary space but also gave potential for spaceships beyond the solar system. I called the book the Star Drive because it is the only known method of getting propulsion of any sort beyond the solar system. It is real and it is not science-fiction. It is astonishing.”

Scotland’s star man

Robert Stirling was born in 1790 at Cloag Farm, Methven, near Perth, to a middle-class family of tenant farmers and lived through the first and second industrial revolutions when ingenuity prevailed.

He was a student at both Edinburgh and Glasgow universities, reading divinity at the latter, but his studies also included the sciences of mechanics, hydro-dynamics, astronomy, optics, electricity and magnetism and, it’s thought, heat.

In 1815, he became a probationary minister, at the same time inventing the engine that converted the heat from a coal fire into motion by expanding and contracting air. A year later he moved to Laigh Kirk in Kilmarnock and was ordained on September 19. A week after his ordination, Stirling lodged the patent application for his heat exchanger and engine.

Author Phillip Hills, an 80-year-old father and grandfather, and founder of the Scotch Malt Whisky Society, said: “Dr Stirling was married and had five of a family. He moved from Kilmarnock to Galston, Ayrshire, where his parishioners loved him. But they couldn’t understand why late at night fires and strange noises would come from the workshop next to the manse. In his spare time he was a brilliant engineer.”

The National Museum of Scotland holds the earliest known example of a Stirling engine, one of only two working models in existence. It was presented to Edinburgh University by Stirling no later than 1825 with a second gifted to Glasgow University in 1827 and on display in the Hunterian.

Hills said: “Part of my intention of writing the book was to waken people to their importance.”

The Star Drive: The True Story of Genius, an Engine and our Future, by Phillip Hills is published by Birlinn

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Paul Reid

© Paul Reid