King of Tartan Noir Ian Rankin could have been crystal gazing when he titled his new book A Song For The Dark Times.

But he reveals his latest John Rebus thriller – out on Thursday – was conceived long before the Covid pandemic gripped the world.

For Rankin, credited with being the UK’s most widely read crime novelist, the dark times came in 2019. And they cast a shadow chillingly similar to that felt by 1930s Britain on the brink of war.

The Fife-born, Edinburgh-based writer said: “It felt to me in the middle of last year that the world was going through some pretty dark times, whether it was Brexit or Trump in the White House, Australia being on fire, or the rise of the far right in many countries.

“There was a polarisation of politics. There is no middle ground where people can talk to each other. It seemed to me the world was getting ugly and angry; and those, to me, were the dark times.”

Echoes of war and its internment camps came to mind. He explained: “It was a time early on in the Second World War. We were locking up people who were different to us; so the guy running the local ice cream parlour with an Italian name would be locked up or the person with the German name who ran the local grocer’s. It was a kind of knee-jerk reaction.

“Although some were eventually released, I felt there was a possibility we were heading towards that kind of mindset again, where we don’t trust our neighbours or the people we meet in day-to-day life.”

In A Song For The Dark Times, he creates a fictional internment camp on the north coast of Scotland that is the focus of local historians and part of the new mystery Rebus is trying to solve. He explained: “It means I can discuss parallels between the way the world was in the late-1930s/early-40s and where we might be heading.

“One of the things about Brexit is it is appealing to that Little Englander notion that we don’t have much in common with other countries; that we are exceptional in a way and that can feed very quickly into xenophobia. I would hate that to happen.”

Lockdown was also a surreal experience for the writer and his family – wife of 34 years Miranda, and sons Jack, 28, and Kit, 26. He said: “To see Princes Street with nobody on it, no buses, no traffic – it was extraordinary. The thing I noticed most was birdsong.”

His greatest challenge was not being able to hug son Kit, who has the rare genetic condition Angelman syndrome, and who lives in a supported community for people with disabilities.

The writer said: “We can see Kit but only over a wall or through a gate because his community has been in solid lockdown from early March. If the weather is bad, we can’t see him. The staff have been amazing but it is really hard on the family. You just have to grit your teeth and get on with it.

“We both went through birthdays in lockdown. We handed the cake and gifts over the wall and the staff took them inside. We didn’t see him open his presents, although the staff did send lots of photos and video.”

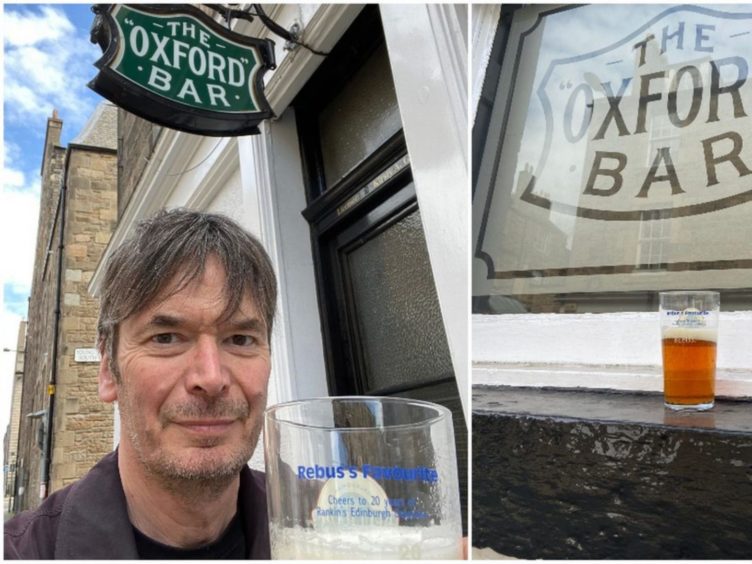

His own celebrations were also curtailed. “Most of my favourite pubs in Edinburgh are small, old-fashioned bars where it is impossible to have social distancing, so they are still under lock and key,” he said.

“My exercise on the day of my birthday was to walk to The Oxford Bar with a glass and a can of beer in my pocket, stand outside, pour a beer, toast myself, drink it and then walk back home again. I did it on my own. I was socially distancing at all times.

“Then my wife made us fish and chips for tea. That was my 60th; that was my big birthday. I haven’t even managed to pick up my bus pass.”

Despite being part of living history, he reveals he is not tempted to document it: “During lockdown a lot of crime writers were thinking, ‘can I write about this?’ As I was strolling through deserted Edinburgh it struck me that anything could be happening behind these locked doors; these deserted jewellers shops, restaurants and five-star hotels; all boarded up, all empty apart from a nightwatchman.

“There is plenty material there but I have become resistant to writing about it because possibly there will be too many Covid novels coming along soon – and who wants to be reminded of it? Readers are going to want an escape from what has happened.”

He set the new Rebus – the 23rd in the series – in the summer of 2019. Had he not, he says he would have been rewriting now instead of looking forward to a launch that will be different to his others. He cannot take it on a physical tour and its promotion will be online.

In it, we find an ageing hero with a chronic lung condition who is out of his comfort zone, physically and emotionally. He is downsizing and trying to reconnect with his estranged daughter, whose husband is missing from their Sutherland home near Tongue.

Rankin revealed: “Since 1987, when I started the series, Rebus has lived up two flights of a tenement. He can’t handle the stairs any more, so the first thing that happens in the new book is he moves to a ground-floor flat and he is not happy about it. Rebus’s flat is real, based on a real tenement in a real street. Then a few weeks ago, someone put online that it was up for sale. It was bizarre.”

Taking Rebus out of Edinburgh was also a stroke of genius. He said: “I thought I’d find a plot that allows me to take him up north, because once he is outside Edinburgh he doesn’t have any colleagues he can call on. He is pretty much on his own trying to solve this mystery. But is he investigating as a detective or as a father who wants to protect his daughter?”

Rankin, too, is out of his comfort zone. “I moved house last year,” he said. “So quite a lot of what Rebus is going through – getting rid of furniture that doesn’t fit the new flat, having to rearrange his records and books – were things that were all personal to me. I have been through that painful process.

“When I wrote the first Rebus novel, I wasn’t married and I didn’t have any kids. He was already divorced with a daughter.

“Getting inside his head was harder for me then than it is now. Now I have a better idea of what he is going through. We all have questions about what kind of world are we leaving behind for the generation coming after us.”

It is time for change, not just for Rebus but also his creator. Rankin revealed: “I don’t have a contract for another book. It is deliberate. I wanted to hit the pause button and think about what I have not done and would want to do.”

When Covid-19 allows, travel is on the cards. He said: “My wife and I wanted to go travelling. She is much more adventurous than me. We did a six-month road trip around America in 1992 with our three-month-old son Jack, and we would love to do a bit of that again. We like long train journeys, too; somewhere I could just sit and read a lot of books and let someone else do the rest.”

A Song For The Dark Times, by Ian Rankin, is published by Orion

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Northcliffe Collection/ANL/Shutterstock

© Northcliffe Collection/ANL/Shutterstock © Ian Rankin / Twitter

© Ian Rankin / Twitter