I have been to the mountaintop. I have seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you -– Martin Luther King Jr in Memphis on APRIL 3, 1968, the day before he was shot dead

It is a tale of one city, two deaths, countless hit records and 12 incendiary months.

In fact, a trilogy of books by Stuart Cosgrove will become a vast tale of three cities – Detroit, Memphis and New York – melding two of his great passions, soul music and American history.

In Memphis 68, the author and broadcaster continues his compelling account of the last tumultuous years of the 1960s as the decade of love shuddered to a halt in cities ablaze with civil unrest, race riots and political assassination.

For Cosgrove, the past streams through the present and he sees the racial division and inequality that stoked revolt in black neighbourhoods 50 years ago on the same streets today.

He said: “There are so many echoes of the past in America today and the more you research, the more you discover. All this happened 50 years ago but sometimes it feels like last week.

“In music, culture and society, threads that were unpicked half a century ago are still unravelling all across America.

“I would be in libraries in Detroit and Memphis, reading old newspapers describing civil unrest and racism and then come out and buy that day’s paper reporting things like the riots in Ferguson and Black Lives Matter.

“It is difficult to argue America has made progress on these issues. It’s impossible to argue that.”

After Detroit 67, the first critically-acclaimed book in his trilogy, Cosgrove heads south to Tennessee where two deaths in a few short months cast a long shadow over the decades to come.

Weeks before New Year’s Eve, on December 9, 1967, Otis Redding, already a Memphis legend at just 26, died in a plane crash along with four of the Bar-Kays, his hugely talented band.

The death of Redding was bad enough but worse was to come four months later when civil rights leader Martin Luther King was assassinated in Memphis, shot dead as he stood on a second-floor balcony of the Lorraine Motel at 6.01pm on April 4, 1968. He was 39. In the city to support a strike by black sanitary workers for better conditions, King had given what was to be his last speech in the city the day before his death.

He said: “I’ve been to the mountaintop … and I’ve looked over and I’ve seen the Promised Land.

“I may not get there with you but I want you to know tonight that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.”

Memphis 68 unfolds through a series of personal histories, whether of performers such as Wilson Pickett; Ernest Withers, a civil rights photographer later exposed as an FBI informant; or a secret agent mysteriously at the scene of King’s assassination.

Each adds another layer to the story, but, after reading volumes of testimony about King’s assassination, Cosgrove is still unsure of what happened. He said: “My opinion changes every day. I am sure that James Earl Ray fired the shot but there were some very strange things happening in Memphis that day.

“How and why Ray was there, the logic and logistics, have never been properly explained.”

Cosgrove spent a month in both Detroit and Memphis researching and found himself honing skills first learned working on his PhD in American history. He said: “It made me realise the importance of primary sources again. This idea that everything is online, anything can be Googled, is just not true.

“I spent weeks poring over months of old newspapers on microfiche and found out about people and events and stories from the time that I would never have found anywhere else.

“Even personal interviews can be unreliable, particularly when you’re talking to people whose story has been told many times before. Sometimes they will tell the story they think you want to hear, not what actually happened.”

The soundtrack to Memphis 68 is provided, inevitably, by the city’s Stax record label. The enduring sound and roster of superstars once suggested the label – launched by white founders but driven by black talent – was destined to rival Motown but, in the wake of King’s assassination, the mood darkened.

Cosgrove said: “At the start, for the time, Stax was a remarkable place where black and white people worked together easily.

“But after Martin Luther King died, the mood in the city changed, attitudes changed and there was more suspicion and distrust.

“His death did not close down Stax but it helped corrode trust and that, step by step, led to the end.”

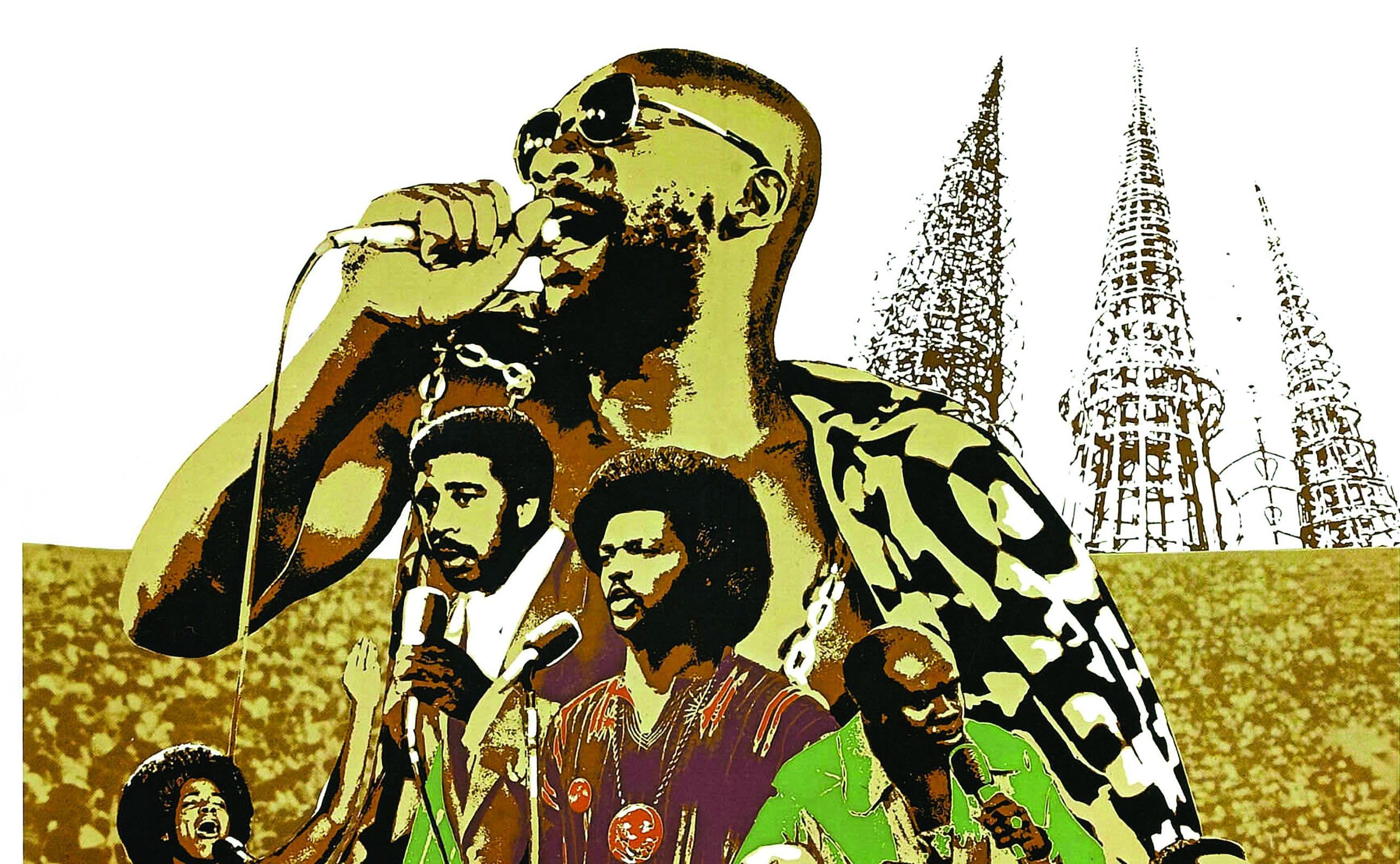

Stax, home to soul superstars like Isaac Hayes and the Staple Singers, staggered on, staging the Wattstax concert in Los Angeles in 1972. It became known as the Black Woodstock and the opening speech by Jesse Jackson would later be sampled by Scottish band Primal Scream on Come Together. But, after 14 turbulent years, the label finally closed in 1975.

After Detroit and Memphis, Cosgrove is turning to New York for the final book of his trilogy. A former NME journalist turned successful Channel 4 executive, he is enthused to be writing again,

He said: “When I was at Channel 4 at the height of Big Brother’s popularity, I remember being in a meeting where we were desperately trying to think of spin-offs and new ways to extend the brand.

“It was hard to convince ourselves we were splitting the atom, and I remember thinking that, if I got the chance, I’d try to do something that meant more to me than Big Brother’s Little Brother.

“Around that time, I went to see the movie Dreamgirls and, coming out, the person I was with asked if Florence Ballard of the Supremes had really been sacked during the Detroit riots or if the timing had been changed for dramatic effect.

“I didn’t know but in the process of finding out, I had the idea of a book about Motown and Detroit then, almost immediately, had the idea of another and then a third.”

Cosgrove, who co-presents BBC Radio Scotland’s Off the Ball and whose passion for Scottish football in general and St Johnstone, in particular, rivals his lifelong love of soul, is now deep into research for New York 69.

Legends like James Brown and Jim Hendrix will feature along with the Apollo, the famous Harlem venue, but, in the book, the music will soundtrack the rise of the militant Black Panthers as heroin grips the ghettos. Again, the relevance of the political and cultural climate 50 years ago to today will be inescapable.

Cosgrove said: “It was the last year of the ’60s. But every ending is a beginning.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe