They came, they painted and… they were largely ignored.

The genius artists of the Impressionist movement might have crafted some of the world’s best-known paintings that would enthral art-lovers for generations but at the time the likes of Claude Monet and Edgar Degas were largely dismissed by the establishment and their work sold for a tiny fraction of the millions it goes for today.

Several Scottish art collectors in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, however, were ahead of their time and their investment in what were then seen as radical and edgy works led to the country becoming home to one of the world’s greatest collections of Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art.

A new exhibition, A Taste For Impressionism: Modern French Art From Millet To Matisse, on display until November at the National Gallery of Scotland (NGS), explores their story, featuring a number of world-famous pieces by Monet, Degas and Gauguin and later work by Van Gogh, Picasso and Matisse.

Professor Frances Fowle, senior curator of French art, said: “A lot of these collectors were ‘new money’ industrialists, often coming from ordinary backgrounds, making their fortune on the back of things like shipbuilding, textiles and heavy metal. Some were merchants as well, engaged in imports and exports.

“They were quite often first generation and more prepared than previous collectors to buy modern, contemporary art.”

Dealers like Alexander Reid, who became friends with Van Gogh while living in Paris in the late-1800s, promoted French art back home and sold Impressionist pieces to industrialists, with the market really getting going in the 1920s.

The exhibition features about 120 paintings, sculptures and works on paper taken from the NGS, as well as loans from Glasgow Museums, Tate, Aberdeen Art Gallery, Berwick Museum and private collections.

The world-renowned holdings are largely down to chance, resulting from a series of innovative purchases by previous gallery directors like Stanley Cursiter and donated items.

These include purchases from Sir Alexander and Rosalind Maitland, who began buying in the 1930s and amassed Van Gogh, Monet and Cezanne pieces, gifted and bequeathed to the NGS in 1960 and 1965.

“If any collector bought impressionist art before the prices really began to rise, then they were very canny,” Fowle said. “They weren’t certain that these artists’ reputations would endure. There’s actually a letter with one of the pictures in the show, Paul Gauguin’s Three Tahitians.

“The Maitlands said they felt worried that they paid quite a high price – £13,500 – for this picture in 1936 and hoped nobody else in Edinburgh found out because it was slightly obscene to spend so much money. I find that fascinating that they kind of felt quite nervous about it.”

The exhibition also aims to rewrite into history a number of the female collectors whose contributions have been overlooked.

This includes champion yachtswoman Elizabeth Workman, who was raised in Helensburgh, as well as Indian-born newspaper editor Rachel Beer, known as “the first Lady of Fleet Street” and the flamboyant socialite Eve Fleming, whose son was Ian, the creator of James Bond.

“I was really interested in the number of women collectors who took an interest in Impressionism,” Fowle said. “They’ve been slightly written out of history, I think, because we tend to think about these big industrialists.

“Sometimes when women bought pictures, it was done in their husband’s name and so they become invisible.”

As Impressionist works became more and more popular in the early 20th Century and fetched increasingly high prices, a side industry in forgeries began to take hold.

This is acknowledged in the exhibition, with a number of counterfeit works among those on display – but left for the visitors to detect themselves.

“What it does is it makes people look much more closely, and try to think as connoisseurs,” Fowle said. “What is it potentially that is wrong about this picture?

“It’s quite interesting, because a lot of people try and guess and get it wrong. I find it fascinating how people formulate these ideas about why they think it’s wrong, how you tell whether art is genuine or not.

“Forgers use all sorts of ruses to pull the wool over people’s eyes. People love programmes like Fake or Fortune and I think it’s quite good to get people involved.”

Hitting the headlines

During the course of preparation work, the gallery hit the headlines worldwide with a discovery made by conservators in Van Gogh’s 1885 painting, Head of a Peasant Woman.

X-ray imaging of the piece, from the Maitlands’ collection, showed hidden on the reverse side a previously undiscovered self-portrait of the Dutch painter.

It was hidden below layers of glue and cardboard thought to have been attached to the back of the canvas to help protect the work.

“Moments like that are incredibly rare,” Fowle said. “The day that it was announced we were interviewed all over the world. My brother lives in Los Angeles, and saw it on NBC News that night. I was also talking to people on a New Zealand breakfast programme.

“It really has an international impact, it’s the Van Gogh phenomenon and the idea of finding something which has been under your nose the whole time, hidden treasure.”

The expert view

Frances Fowle on some of the exhibitions highlights.

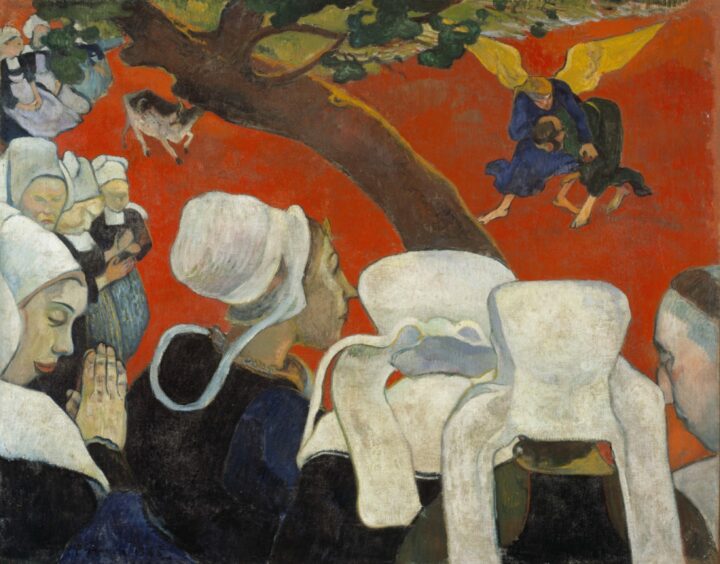

Paul Gauguin – Vision of the Sermon (Jacob Wrestling with the Angel), 1888

This is probably the most important work in the entire collection.

Gauguin was quite an interesting artist with an exotic background, he was French-born but spent his childhood in Peru. He became a stockbroker in Paris and then got married, had five children and then decided to give it all up and become a painter.

He went to Brittany trying to find an innocent and primitive way of life. His idea was to develop this style of painting which expressed the simplicity of the people that he encountered there and their superstitions and religions.

This was regarded as the first painting to not paint reality as you see it, but to paint what you have in your mind.

It shows women in Breton costume listening to a sermon. On the right is a priest who has Gauguin’s own features, a self-portrait, and then top right is Jacob wrestling with the angel from the bible, which is happening in their imagination.

It was really innovative, almost like a thought bubble in a way. The style was supposedly influenced by Japanese prints and stained glass.

It’s a symbolist painting, evoking ideas rather than copying reality directly. The struggle between Jacob and the angel traditionally represents the struggle between the spirit and the flesh.

Pablo Picasso – Mère et enfant [Mother and Child], 1902

This picture comes from Picasso’s blue period. it shows a woman and child in a prison laundry. It looks like it’s just a painting of motherhood but it’s actually a poignant image of poverty and hardship.

He deliberately chose this sort of subject. the blue is used almost symbolically to express sadness and the poignancy of the suffering in a way. It’s a rather moving image, it’s quite small but very beautiful.

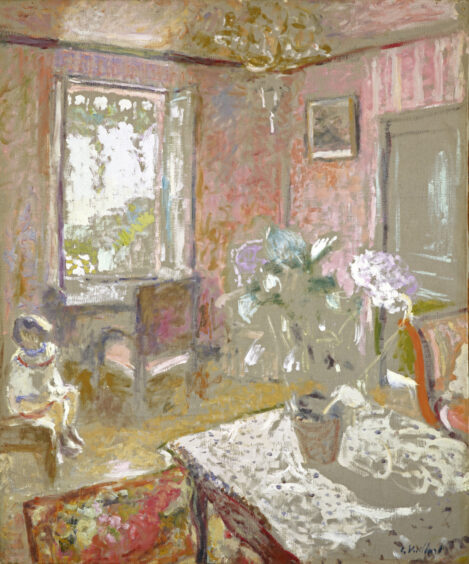

Edouard Vuillard – La Chambre rose [The Pink Bedroom], about 1910 – 1911

This is another from the Maitlands’ collection. Vuillard seems to have been a really popular artist. He was the generation that followed the Impressionists and is part of a whole group known as Les Nabis, or The Prophets.

They were very interested in the decorative. His mother was a seamstress so he was used to patterns and fabrics. The painting has that Impressionist interest in light and shade but he’s been quite experimental in the way he paints, leaving a lot of the patch of ground unpainted so that the shadow of the flowerpot on the table is just bare underpaint.

There are lots of areas left unpainted which was quite radical at the time. He also liked these intimate interiors and slightly inconsequential subject matter which was a new idea at the time.

There were two big exhibitions of Vuillard’s paintings held by Alexander Reid in Glasgow in 1919/20 which is why there were so many in Scottish collections.

Jules Bastien-Lepage – Pas Mèche (Nothing Doing), 1882

He was a realist painter but he was sometimes described as an impressionist because he painted large scale canvasses he’d rig up outdoors but finish off in the studio.

He liked to paint more realist subjects but they’re slightly sentimental in some ways. He painted often in his home town in France.

This picture was bought in 1913 by the Galleries for £1800, which was almost twice the annual budget.

He was a really important artist in terms of Scottish paintings, the Glasgow Boys really liked his work and they really admired him.

This work was in the collection of George McCulloch, who came from Glasgow. He started life as a shipbuilder, had a disastrous career which ended up with him having to emigrate to Australia to seek his fortune as a sheep farmer.

He ended up in this area called Broken Hill, which is where they found silver mines. He made an absolute fortune and came back to London where he had a big house and a huge collection.

He only bought pictures by artists who worked during his lifetime. Bastien-Lepage was born the same year McCulloch was, so he particularly liked him.

Auguste Rodin – The Young Mother, sculpted 1885

This is another part of the Maitland story. Rosalind was an accomplished pianist and conductor. Her mother used to take her to Europe on culture tours and one of the things they did was visit Rodin’s studio.

Rosalind wanted to buy The Kiss, a really famous work and would’ve been a fantastic thing for us to end up having, but instead her mother persuaded her to buy this.

A Taste For Impressionism: Modern French Art From Millet To Matisse, National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh, until November 13

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Graeme Yule

© Graeme Yule