An extraordinary trove of letters written more than 175 years ago by Isambard Kingdom Brunel have been discovered hidden amongst some old maps and charts.

Experts say the “remarkable and extremely rare” find – one of the largest collections of Brunel’s writings to be uncovered in recent years – provides significant new insights into the life of Britain’s greatest engineer, during the most prolific years of his life.

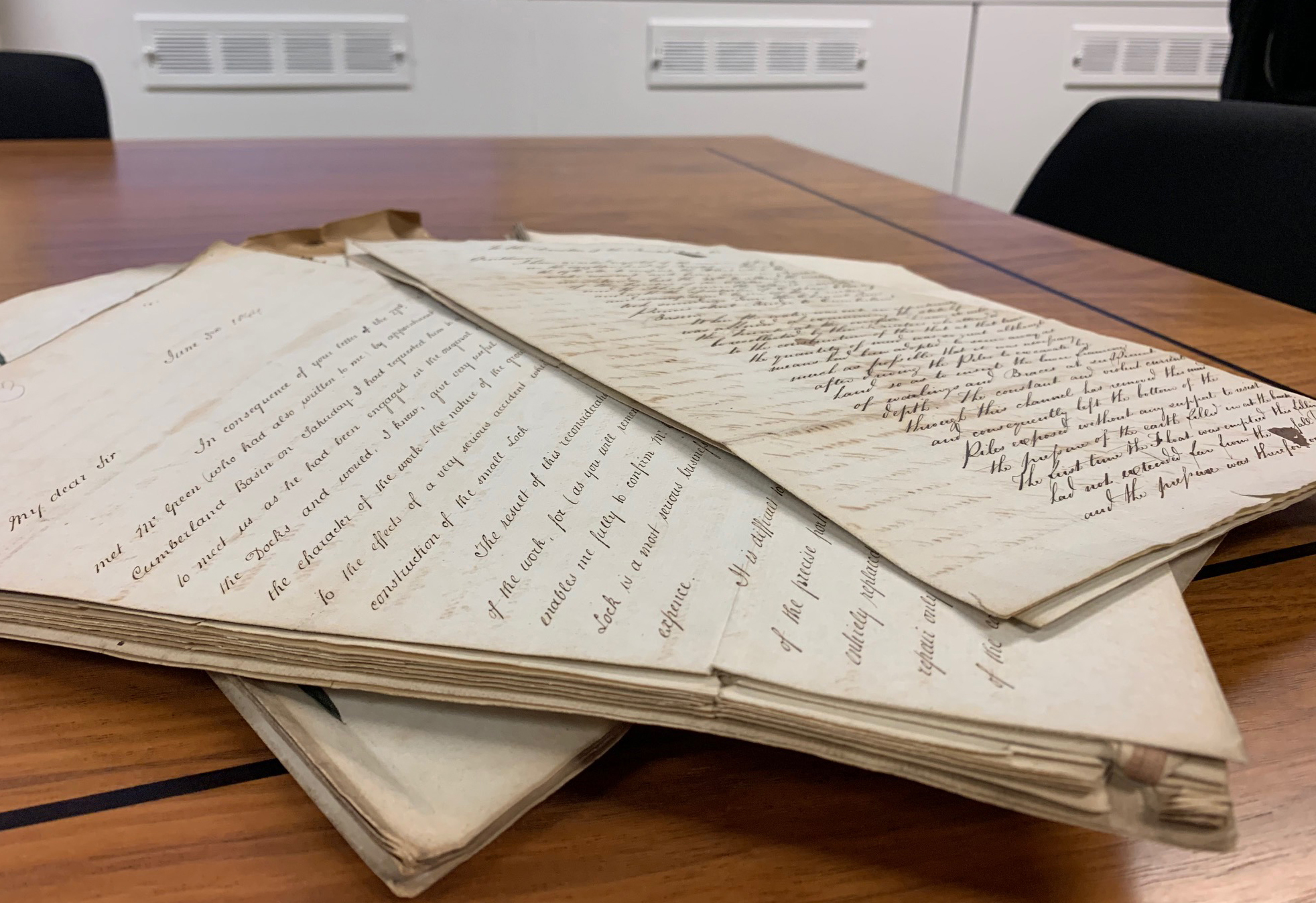

A total of 15 documents authored by Brunel from 1832 to 1846, found tucked into an old yellowing folder at Bristol Port by a book researcher, give a new perspective on the period in which he was appointed engineer to Clifton Suspension Bridge, launched the SS Great Britain, and completed the Great Western Railway.

Amongst the revelations are surprising reflections from Brunel about his concerns for the environmental impact of the Industrial Revolution, and typical examples of his perfectionism as he attacked a series of “entirely useless” efforts undertaken against his counsel.

Bristol Port has donated the entire collection to the SS Great Britain Trust and Brunel Institute, where they are being transcribed and prepared for display to the public.

Nick Booth, head of collections at the SS Great Britain Trust, said: “The documents provide a remarkable and unique insight into Brunel in his formative years.

“It is extremely rare to receive a single letter or report written by Brunel, so we are enormously grateful to receive such a generous donation of a whole collection.

“It will allow us to tell the story of Brunel in Bristol, right next to the floating harbour which he wrote about over 175 years ago.”

Most of the correspondence is from Brunel to the directors of the Bristol Dock Company and addresses the problem of the city’s floating harbour becoming laden with mud, causing large vessels to run aground.

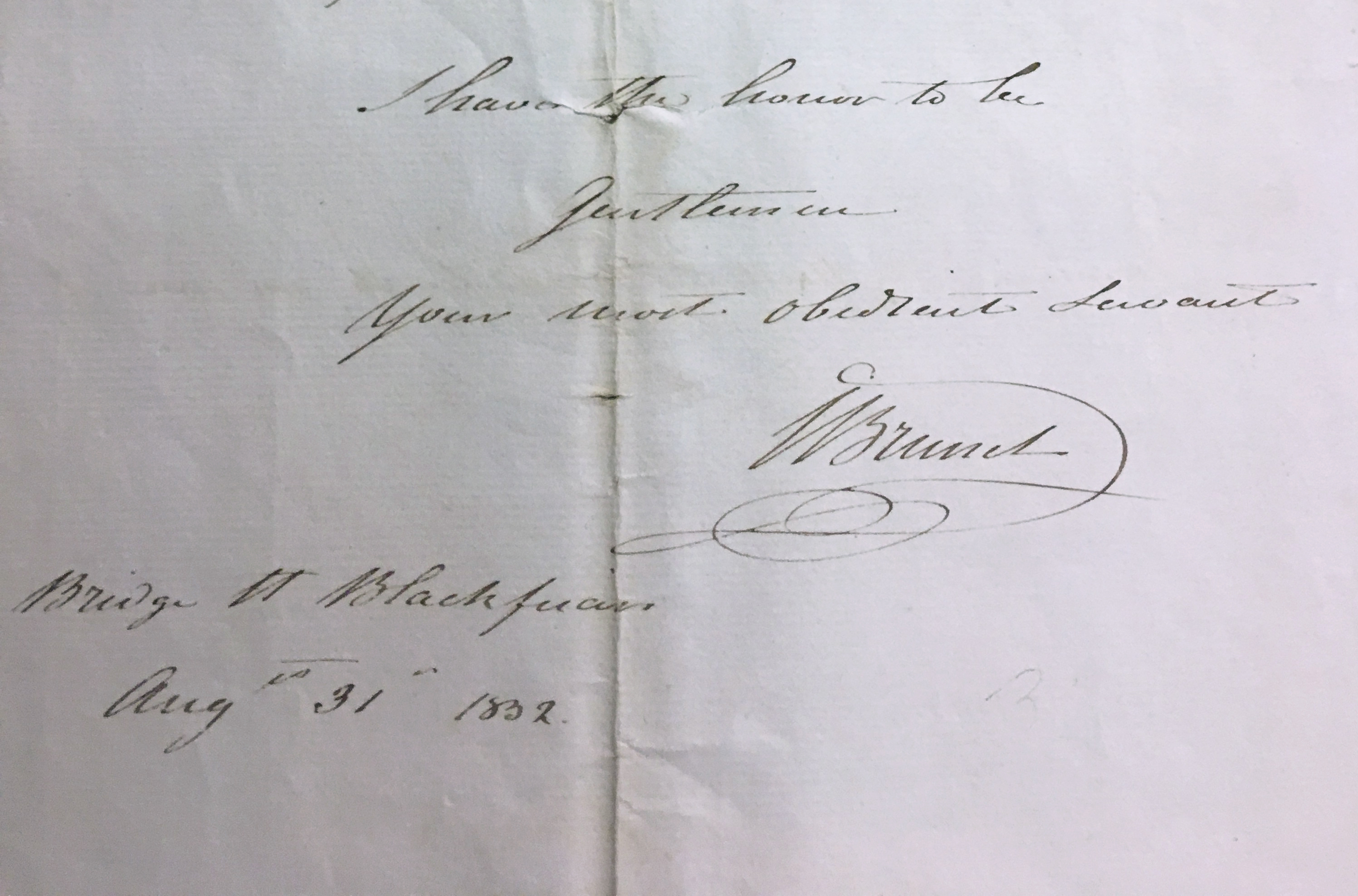

There are four letters from 1833 to 1846 and five reports from 1832 to 1842, as well as quotes from Brunel for completing work on the Southern Entrance dock.

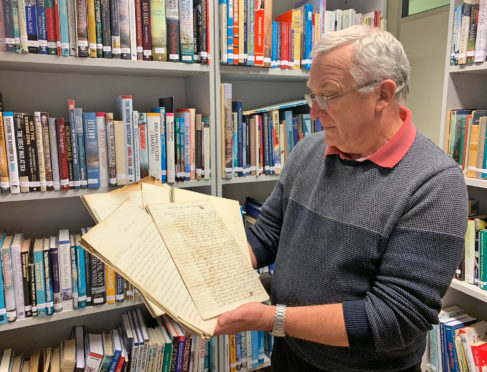

The discovery was made by Roger Henley, a retired engineer, who was sifting through papers in the archive room at Bristol Port Company’s St Andrew’s House in Avonmouth as part of his research for a new book about the Port.

Mr Henley said: “There are thousands of rolls of historic papers in the archive room and as I was going through them, I found a yellowing folder, inside of which were a stack of carefully penned, hand written documents.

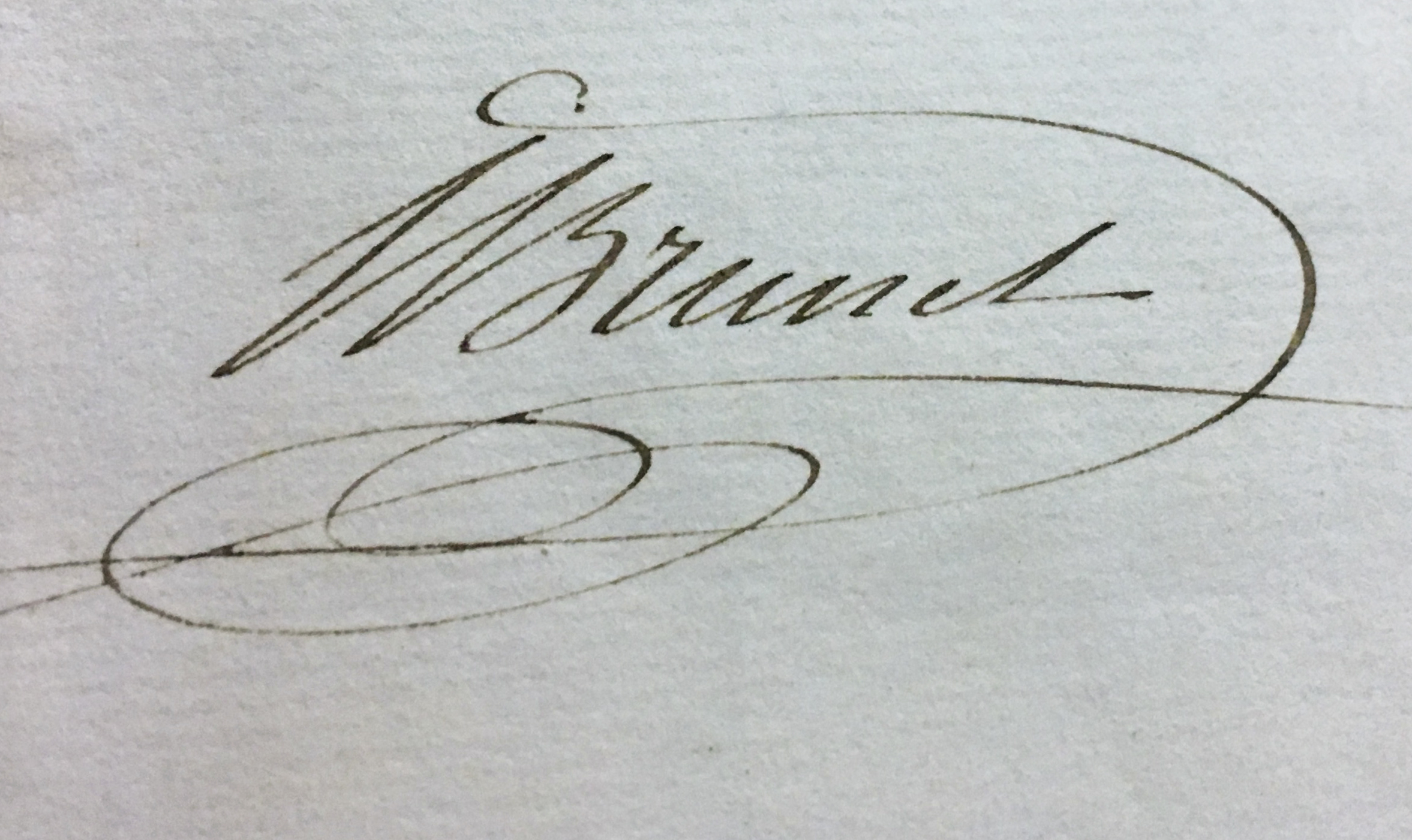

“They didn’t stand out until I got to the bottom of the first letter and to my amazement realised it was signed I.K. Brunel.

“I didn’t need an introduction to that name! It was an incredible moment and a surreal feeling to realise I had in my hands original letters penned by the world’s greatest engineer.”

Terence Mordaunt, the co-owner of Bristol Port Company, officially handed over the collection.

“The history and heritage of Bristol docks has always been extremely important to us and to make this discovery of Brunel writing to our predecessors at the Port 175 years ago was extraordinary,” he said.

“We are delighted they will now be made available to the public to read and enjoy.”

The SS Great Britain Collection forms part of the world’s finest collection of original source Brunel materials at the Brunel Institute. The Port’s gift of the letters is one of the largest individual donations in recent history.

Brunel’s letters show he was ahead of his time

In some of the letters, Isambard Kingdom Brunel was surprisingly ahead of his time in worrying about the environmental impact of building modern Britain.

Writing in 1842 about the floating harbour at the heart of Bristol he expressed concern that the “abuses of using the Float as a common receptacle for rubbish have immensely increased”.

He cited the waste created by his Great Western Railway, as well as other industries such as a local cotton mill, iron merchants, and ship, locomotive and bridge builders, all polluting water supplies.

Brunel described the issue as “in some measure unavoidable” but added that “I fear still more from the apparent tendency of all persons to use the Float as a good receiver for that which cannot easily be got rid of elsewhere.”

Nick Booth, head of collections at the SS Great Britain Trust, said: “It’s a fascinating insight into a side of Brunel we have not seen before.

“It would be going too far to suggest Brunel was an environmentalist – he was a Victorian engineer after all – and his concerns are foremost about the implications for trade.

“But this does provide a glimpse of genuine concern about pollution and is perhaps another way Britain’s greatest engineer was way ahead of his time.”

When the Bristol Dock Company first employed a nervous young engineer named Isambard Kingdom Brunel as a consultant it was a feather in his cap.

A decade later Brunel was one of the most famous men in Britain – and no longer afraid to speak his mind in the most forthright of language, even to his clients.

In a report addressed to the directors of Bristol Docks on January 31 1842, – while the SS Great Britain was still being built onsite – he berated them for failing to act upon his earlier recommendations to prevent ships getting stuck in the mud of the city’s floating harbour.

He attacked them for a “general abandonment of care” and the “monstrous abuses by which the Channel of the upper part of the Float has been wilfully and wantonly choked up”.

Brunel repeatedly cites the recommendations he had made in previous years: “I need hardly remind you that these measures were never adopted.”

He added later that “past experience leads me to conclude that it is useless to continue to recommend the adoption of a system which is not practically carried out.”

Brunel went on to recommend further measures – at a cost he estimated of £6,000 to 6,500 – and finished with his characteristic sign off “I am Gentlemen, your obedient servant, IK Brunel”.

Mr Booth said: “It is fascinating to document how Brunel develops over this 14-year period, the most formative years of his career, and how he gets more confident and full of conviction with his language.

“You also get a sense of how systematic he was in keeping all his reports to refer back to.”

The documents also track Brunel’s rise in fame and confidence.

In his early letters the language is carefully balanced.

In later correspondence he criticises various ideas or actions of others’ as “useless” – using the word repeatedly in many of his letters.

He describes issues as “evils” and even criticises the original Act of Parliament which created the Floating Harbour in Bristol as being wrong in the first place.

The correspondence focuses almost entirely on the issue of keeping trade coming in and out of Bristol docks by addressing the problem of the floating harbour becoming laden with mud, causing large vessels to run aground.

Mr Booth explained: “This is a first real insight into Brunel’s work on Bristol docks, and we begin to see how the way things are now can be traced back to Brunel.

“He mentions many things that remain part of the fabric of the city today – Clifton Suspension Bridge, of course, but also Cumberland Basin, the Princess Street Bridge and how Overfill Yard became Underfill Yard.

“It’s a really important account of the dock and harbour’s history.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe