He grew up in chaos on a housing scheme on the south side of Glasgow, the youngest son of a single mother caught in the horns of a ferocious addiction to alcohol.

On Thursday, he became the toast of the literary world, winning the Booker Prize for the novel shaped by his traumatic childhood.

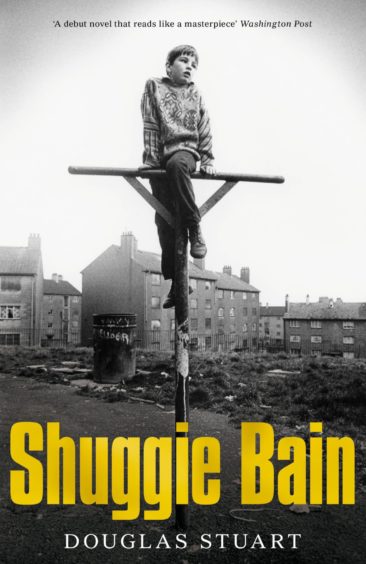

Douglas Stuart’s debut, Shuggie Bain, was the unanimous winner of the annual prize of £50,000, and the keys to a prestigious career in the world of storytelling. He’s only the second Scot to win the prize, following James Kelman in 1994 for How Late it Was, How Late.

For 44-year-old Douglas, the story of the child’s devotion to a mother in a spiral of tragedy flecked with the agony of crushed hope was one he only started telling for himself.

His mother died before he finished secondary school, and he left Glasgow to study textiles at college in Galashiels soon after.

It was the beginning of a career which would see him move to America building a successful career as a fashion designer with Gap, Ralph Lauren and Calvin Klein. But his move was ultimately the start of his return to his childhood – Douglas began writing Shuggie Bain, aged 30, in hotels and airports as he flew around the world.

Douglas said: “Firstly, I was proving something to myself. I didn’t come through a writers’ workshop, I didn’t have a community of writers, I did it because I loved it, and wanted to express something, and also because I feel a little bit like a person torn in two halves.

“There’s the boy that I was and how I grew up – I lost my own mother to addiction when I was still a kid, and I never knew my father – and the boy brought to this point by the transformative power of education.

“Thank God Scotland is a country that affords its poorest kids access to fantastic education as I used that.”

Although Shuggie Bain is not an autobiography, it borrows heavily from Douglas’ life. The novel is dedicated to his late mother, referenced respectfully only as AED. It tells the story of Agnes Bain, a once-proud woman lost to the devastation of bitter circumstances in ’80s Scotland when industry was on its knees. It’s bleak but compelling, a story as brutal as the men around her and as tender as the voice of the child when he speaks to his mother.

Douglas said: “I wrote about those feelings and what it is like to be around that chaos, and I understand it because that’s how I grew up.

“I went to Crookston Castle Secondary and it was bedlam, because kids were struggling. Pollok in the early ’90s was such a place of deprivation and school was a rammy every single day. Books were something I couldn’t find peace for until I turned 16 and a lot of the kids left.

“I had space and time to focus on books, but I went into textiles first as it was seen as a creative field and also a trade. I never imagined that would become a career in fashion.”

And now @NicolaSturgeon's book of 2020 is the #2020BookerPrize winner! Happy #BookWeekScotland, @Doug_D_Stuart! https://t.co/T8suN3xpNg

— Book Week Scotland (@BookWeekScot) November 19, 2020

Douglas lives in New York with his art curator husband Michael. It was several years after he started writing Shuggie before he shared his writing

He said: “My mother was a single mother who raised me on benefits, a Monday book and a Tuesday book. It’s a stretch to say I’m working class because I don’t remember my mum working for very long.

“My mother would be sober for periods, sometimes a week, sometimes more but alcohol was always a feature of my childhood, and of the community around me.

“On the scheme we lived on other women were struggling. Men were losing their jobs and families were coming apart. A lot of writers write about alcoholism as a solitary thing and some days it was like that, my mother drinking at home by herself.

“But it’s also a gregarious disease, with a lot of community in it, good and bad. I wanted to show that in Shuggie – this big chorus of characters who all intersect with Agnes’ addiction. Someone asked me the other day if it gave me PTSD. Poor kids don’t get to reflect like that, they just have to keep going, ploughing through.”

Rejected by 32 publishers, Shuggie Bain was finally published first in the States, where praise has been fulsome, if not without questions for Douglas, like what do gallus, glaikit and boak mean?

He said: “The reception has been phenomenal. Though the book is set in a time and place, the things it touches on are universal. America has many places that have been deindustrialised. And addiction sweeps in when hope leaves.

“I’ve spent months talking to people here about the history of Glasgow, its geography and the socio-economic outlook.

“And I’ve had to explain a lot of Scottish vernacular. But I couldn’t imagine writing a book about Glasgow that didn’t show its language. It’s one of the most beautiful things about the city and one of the most creative things that we have as a people. We’re forever putting sentences together in really startling ways. I love that.

“But feelings of inferiority plague working-class writers and that stops a lot of voices with a lot of things to say that never make it to the page. My advice is – bring your experience to the page any way you can.”

Douglas is working on a follow-up, also set in Glasgow, about two teenage boys falling in love. There’s also a collection of short stories due.

He added: “I never promised myself a book and I never promised myself that anyone would ever read it. I did it because it brought me healing and pleasure.”

Whether on business in China or Italy, during the writing of the book his mind after meetings was on communities such as Sighthill, Lanarkshire, Dennistoun, Shawlands and Pollok during the industrial unrest of the ’80s.

He said: “We talk about men losing their jobs when Ravenscraig, the coal mines and shipyards shut. But what happened to the women? That’s what I wanted to do a wee bit with Shuggie.”

While bleak, the Shuggie Bain story is ultimately one of survival.

“It’s about love,” said Douglas. “Children have a tenacious love for flawed parents. It is quite shocking, quite harrowing, but it’s also just life. I don’t see the darkness in it any more. It’s very narrow, but I see the hope.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © MARTYN PICKERSGILL/BOOKER PRIZE

© MARTYN PICKERSGILL/BOOKER PRIZE © ITV/Shutterstock

© ITV/Shutterstock © David Parry/PA Wire

© David Parry/PA Wire