It’s not often you hear senior police officers accused of conspiracy to pervert the course of justice. When the accusation comes from other senior officers and concerns one of Scotland’s most notorious murder investigations, it’s stop-the-clocks time.

This happens in Bible John: Creation Of A Serial Killer, a podcast by journalist Audrey Gillan. It concluded this week after peeling away the truth from the myths around the bogeyman, who has haunted Scotland for years. Gillan focuses on the women who lost their lives but police misogyny, incompetence and conspiracy is another recurring theme.

Patricia Docker, Jemima McDonald and Helen Puttock were mothers aged 25, 31 and 29 respectively. They had been “at the dancing” in the Barrowland Ballroom, but would be found near their homes, beaten and strangled to death in 1968 and 1969.

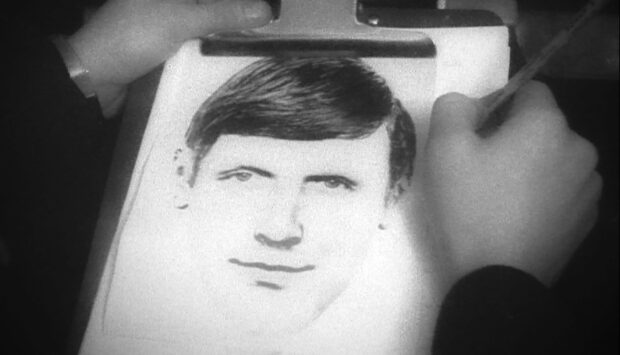

It was only after Helen’s death that police had a reliable sighting. Helen and her sister Jean shared a taxi with a clean-cut “mammie’s boy” who quoted from the Bible and talked of his religious upbringing. Jean’s evidence is recreated by Elaine C Smith, rather brilliantly, in the podcast. In 1969, a journalist coined the term Bible John and police played along. But the killer was never caught.

The case reopened in the 1990s, after the emergence of DNA technology. A new team, led by Detective Chief Inspector Jim McEwan, trawled the original investigation notes. They discovered a man called John Irvine McInnes was visited by senior officers days after Helen’s murder but was never put before her sister or any other witness. It turns out this man, who was religious, was the cousin of one police officer who was close to another, Joe Beattie, who happened to lead the original investigation.

When the 1990s detectives interviewed this retired officer, James McInnes, he was aggressive, evasive and downplayed his role in the investigation.

In fact, he was responsible for finger-printing the taxi taken by Helen and “Bible John” the night she died. No prints were recorded. That taxi driver and a bouncer who saw the suspect, were never invited to line-ups. Many key witnesses were ignored.

In the 1990s, witnesses shown McInnes’s picture immediately identified him. McInnes’s body was exhumed, but DNA samples were inconclusive.

McEwan’s team also found evidence, ignored by police at the time, that Helen Puttock’s husband, George, was violent towards her. When Beattie strip-searched George after the murder, he assured him: “I knew you had nothing to do with this, son.”

Yet the same detective told a journalist in the 1970s he found “rake marks” from Helen’s nails on her husband’s arms. Instead of ringing alarm bells, Beattie viewed this as evidence of her “bad temper”. This is not to suggest McInnes or George Puttock killed Helen, simply that the inquiry was deeply flawed.

Judgments were made about Helen and the others in written police records – “they were promiscuous…drank too much…should not have been out” – Beattie even said his team was not motivated to find Helen’s killer “because of what she was…”

The 1990s detectives failed to get a DNA match, but they uncovered leads about the crimes and possible police corruption. Yet the Lord Advocate in 1996 closed the case. It is to the great credit of Gillan that this scandal has now been properly detailed.

Does it matter decades later? Women are still murdered by men and misogyny remains rife in police forces. But, yes, it does matter and the errors then – the murder inquiries, the cover-ups, the decision to close the cases – should be corrected now.

It may be delayed but three women and their families still deserve justice.

Joan McAlpine is a journalist, commentator and former MSP

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe