THE Great War was a conflict that featured many firsts, with every side coming up with horribly-efficient new ways of killing each other.

It was the war that saw incredible leaps forward in technology, with some battles involving men who didn’t even have protective helmets, relying on pack horses, while others had sophisticated planes that could drop torpedoes on enemy shipping.

The mixture of powerful weapons and men lacking proper cover or transport would help lead to so many deaths, but few new inventions made the world sit up and stare like the tank.

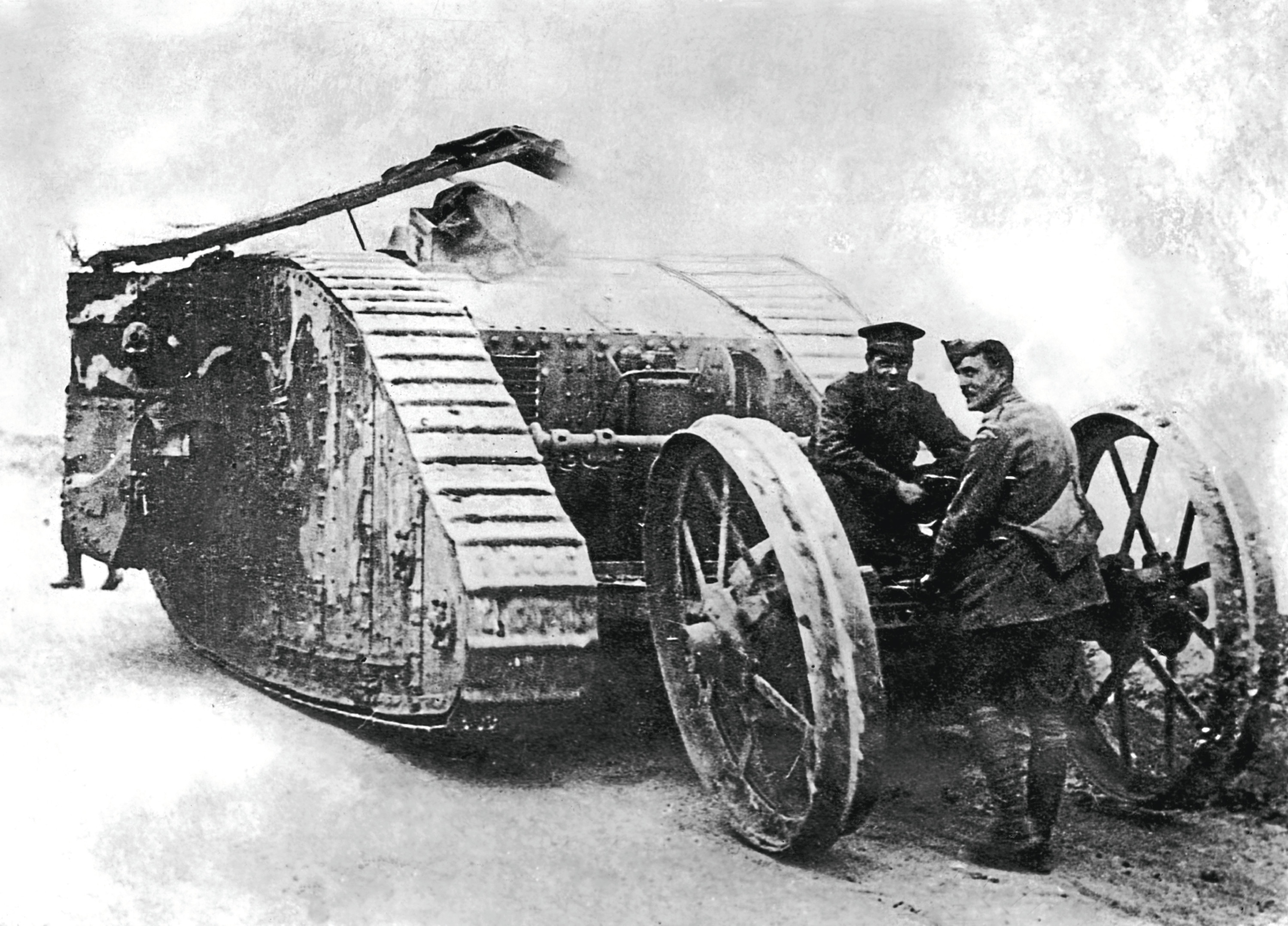

This month is exactly a century since British Mark I tanks first saw action, at the Battle of Flers-Courcelette in France.

With the Canadian Corps and the New Zealand Division fighting for the first time, they made headlines around the world, but it was the formidable appearance of these large metal machines on tracks that stunned everyone.

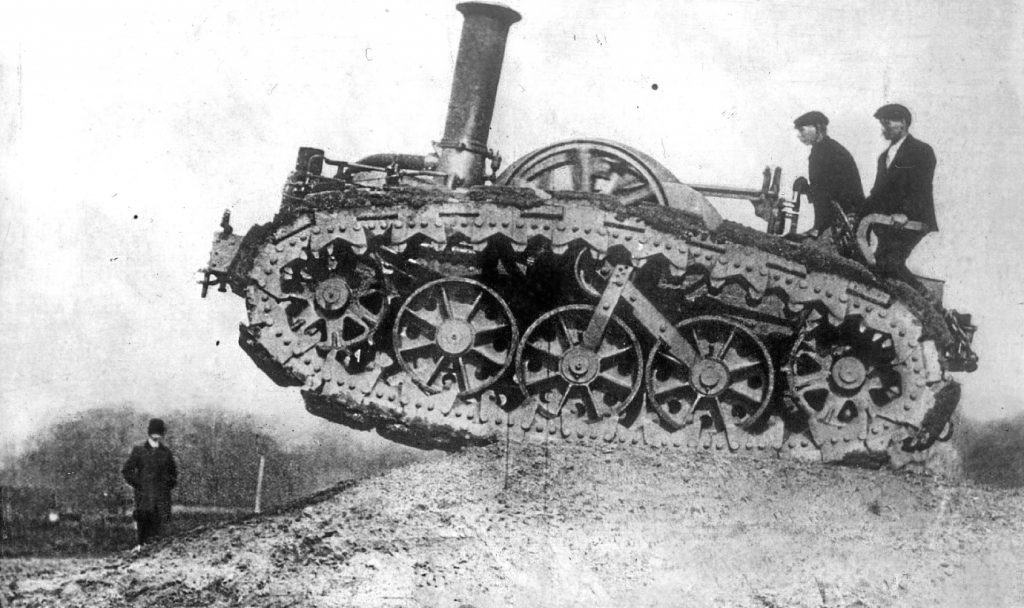

The concept had been around for a while, having begun when farmers looked for ways to move large machinery around muddy farmland, with the notion of tracks instead of wheels being at the core of it.

But put a large gun on top, and build it with materials that would see ordinary bullets simply bounce off it?

This thing could be a real game-changer in wartime.

And so tanks were introduced at the Battle of the Somme and, while these early ones were temperamental and unreliable, they put the fear of God into the enemy.

They also provided a bit more mobility, and in years to come, would mean troops didn’t have to dig into trenches and crawl forward, a few perilous inches at a time under fire.

Tanks could just roar across the surface, and crush almost anything that got in their way.

Caterpillar tracks, it turned out, were just the job, and by the Second World War all sides had their own extremely-efficient versions of the original tank.

During the Great War, trenches had seen the end of heavy cavalry use, as this was no landscape for horses, getting stuck in mud or breaking their legs as they fell into holes everywhere.

Senior military men, however, traditional as ever, kicked up a real stink out of fear that the cavalry would disappear. They didn’t much care for these new-fangled armoured vehicles.

It was a Lieutenant-Colonel Ernest Swinton who had proposed the development of a new fighting vehicle, something capable of beating the armoured cars already in use — and, of course, one that didn’t have to worry about the surface it would be moving upon.

By the summer of 1915, he was told what it should have, and these orders included a top speed of 4mph, the ability to turn sharply, even at top speed, being able to climb parapets, cross eight-foot gaps, and crucially, have a large artillery gun and smaller machine guns.

Winston Churchill was an early fan, loved the sound of all this, and would have given it the thumbs-up. Alas, at that time, he was not the hero he would become, and nobody listened.

It was actually the stalemate on the Western Front that drove the top brass to finally making a decision about the tank, as it would become known.

They would base the Mark I on Big Willie, a caterpillar-track vehicle designed by a Lieutenant W Wilson and William Tritton.

Big Willie was based on a previous smaller version, and featured guns mounted on several blisters around its hull.

The first proper tank came off the production line on September 8, 1915, and within two days, its track had simply dropped off.

Newer versions, though, tested in front of Government bigwigs, thankfully remained intact, looked formidable and won them over with their sheer power.

With that dodgy beginning, it’s incredible to think that in the September of 1916, 36 of the new tanks attacked en masse at the Somme.

There had been 50, but the rest had been unable to cope with the horrendous conditions there and became bogged down or broke altogether.

It didn’t matter — the 36 that did go into battle would change the history of warfare.

Ernest Swinton had been very keen to see both the tank and infantry work together, co-operating, and he seems to have seen the tank as just a machine that would provide some back-up for the majority of soldiers, who would still be on foot.

In years to come, as tanks got more mobile, powerful and impregnable, there would be many battles with almost no infantry and every combatant inside his tank.

Alarmingly, we had struggled to even find men to do the job of guiding these metal beasts across the battlefields — only the wealthiest Britons had much experience of mechanised vehicles back then.

People, therefore, had to be trained in how to use them, how to look after them, how to fire guns while in them, and that would take time.

Ernest Swinton, who would become a Major General, was told to get them ready in double-quick time, and those who signed up to join the Armoured Car Section of the Motor Machine Gun Service came from the motor trade.

In other words, they knew more than most about moving vehicles, but next to nothing about how to use them during battle!

The MMGS, by the way, was given that name so that no German spies would work out that we might have something new up our sleeves.

Artillery, however, had proved pathetic at the Somme, and the tanks were thrown into action, inexperienced crews and all.

One tank commander would write: “I and my crew did not have a tank of our own the whole time we were in England. Ours went wrong the day it arrived!

“We had no reconnaissance or map reading, no practices or lectures on the compass, no signalling and no practice in considering orders.

“We had no knowledge of where to look for information that would be necessary for us as tank commanders. Nor did we know what information we should be likely to require.”

Regardless of all that, the tank had arrived and was here to stay, a crucial part of warfare to this day, 100 years later.

READ MORE

Ledger reveals extent of damage to Kirk buildings during Second World War

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe