Jack Vettriano wants us to know he’s still alive. It seems a little odd since, if one of the world’s most popular artists had died, we’d almost certainly have heard about it by now.

After the last few years, however, the Methil-born painter is perhaps a little surprised he’s still here. “I’ve had a terrible three years,” he says. “I dislocated my shoulder a few years ago and that’s been troubling me. It’s my painting side.

“There are some things I was able to do with a paint brush that I can’t now. If I try it, a muscle cramps in my upper arm.

“Then, last week I fell in the snow, damaging my leg. Jeez, I should be speaking to The Lancet instead of you. So I’ve not been painting. My exhibitions have been cancelled until next year. Anybody that tells you life gets easier as you get older is having you on.

“I’m speaking to you now because I want the people of Scotland to know I’m still here.”

Not that Jack could paint even if his arm miraculously healed. His art might be present in countless homes across the country but the artist isn’t even a presence in his own home these days; the 69-year-old is afraid to return there for fear of contracting Covid. At the moment, he is cloistered in an Edinburgh hotel room, severed from the brushes and easels at his workshop in London.

He arrived in the Scottish capital just as the pandemic began and these days cuts a solitary figure, moodily wandering the deserted, grand hotel; it almost seems a fine subject for one of his famously moody paintings.

Jack says he is doing well despite the setbacks which include the end of what he describes as a “destructive” relationship. “I’ve had to go on a course of strong anti-depressants because I don’t know what’s going to happen to me,” he adds. “And I do suffer a bit from insomnia, especially when the future is uncertain. You don’t have a partner, you’re 69, you’re cut off from your home. I’d like to find a partner. But there’s no hint of that at the moment. I’m not in a hurry to get back into one but as you get older you need a partner. That’s what I would like.”

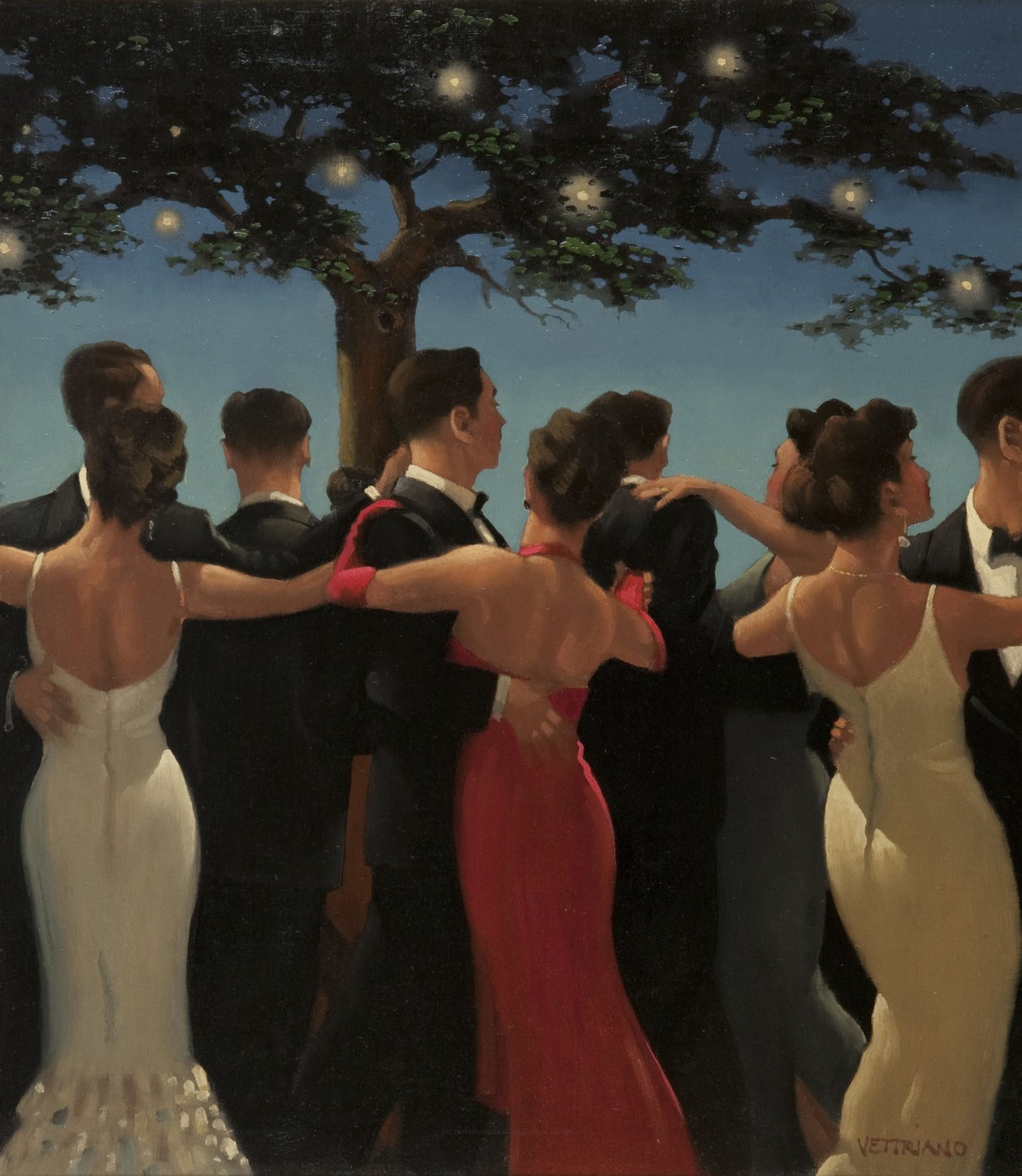

In the #MeToo era, his paintings of women, of beautiful brunette, 1950s femme fatales, are even more likely to attract accusations that he is objectifying his models but, Jack insists, the dynamic is more complicated.

“The proper definition of a muse is she is your lover, she is your critic, she comes up with ideas,” he says. “I’ve painted probably 20 women but never two or three at a time. I like to get to know them. I’ve never approached a woman. What I do like is being introduced to them.

“There’s just a certain look that I know when I see. I’m not sure I can describe it. It’s a kind of slightly dated look. One woman said to me she’d love to step into one of my paintings, as long as she could step back out again.”

Jack liked to pretend he was James Bond when he was younger. Yet he insists that, thanks to the working class values instilled in him by his father, Bill, he has always treated the women in his paintings well. “I was close to my dad,” he adds. “He was a wonderful man.

“He never said, ‘Why don’t you study and go to university?’ He didn’t push me at all, but he did teach me right from wrong. If I had stayed in Methil I would probably be dead from a heroin overdose.”

As well as his workshop, Jack is cut off from his bike. He uses it to keep fit; looking good, unsurprisingly for a man so keen to render beauty and elegance on canvas, is important to him.

“I remember my dad at 70, but mentally he retired when he was 30. When you start wearing slippers to go to the shops you’re in trouble. I’ve been careful with myself. In London I used to cycle around Battersea Park to keep fit. And I try to be fashionable without looking like a bloody idiot. Sometimes I have to shake myself and say, ‘don’t try that, you’re 69’. In my head I’m 27.”

Perhaps mindful of his working-class background, one of Jack’s passions is supporting young artists. Throughout lockdown, many have been unable to earn, yet he is unwilling to suggest the Scottish Government should do more to help. “I do support young artists but that’s something I won’t discuss,” he said. “I’m very generous because I can be. I don’t want to go and lecture students. I do what I can, which is give money.

“I’m not trying to come across like bloody John Paul Getty or anything. I’m reluctant to comment on government support because I haven’t really thought about it, because I’m in a position where I don’t need to think about it.”

Although unable to pick up a brush for the moment, Jack says he still has plenty of good ideas, although the world’s current crisis doesn’t figure highly. His sketches of elegant women and dapper gentlemen might lose their mystique if they were wearing Covid-compliant masks; perhaps that’s why his plans don’t include any pandemic-related paintings.

“There will be a great number of writers and artists who will take advantage of this situation and start to paint all sorts of virus-related art,” he says.

“I don’t want to be too unkind but it scares me they’ll take advantage of it. When lockdown finishes and people get back to work the last thing people will want to see are paintings about a virus.

“There will be people out there who think that’s what people want so that’s what they’ll give them. I’ve got nothing to paint about the virus. Nothing at all. It would be very easy to get access to a hospital ward given my popularity, if you like.

“And I could take some photographs and paint from those. But who wants to see a painting of somebody on a ventilator?”

Before he returns to his easel, Jack is stuck with the four walls of his hotel and a subscription to a streaming service. He plans to rewatch Breaking Bad and, despite his injuries and sense of isolation, insists overall the picture, for him, is upbeat even though his skill with a remote control isn’t quite what it is with a paintbrush.

“Thank God for Netflix,” he explains. “The Queen’s Gambit has been recommended to me. I’m watching something called Crime Scene by mistake, I was trying to watch something else.

“I’m terrified of this digital world that I lose Netflix when I sit on the bloody remote. I press the buttons and nothing happens. Other than that, I’m feeling quite good.”

The best-selling art print in the UK is The Singing Butler yet although prints hang on walls in rooms across the country, and the original sold for £750,000 at auction in 2004, it didn’t make Jack Vettriano a fortune.

“The one that changed everything for me was The Singing Butler,” says Vettriano. “It was done right at the very start of my career and at the moment has sold well into the millions worldwide.

“Of course it fetched three quarters of a million at auction but originally it sold at auction for £3,000. A thousand went to the auction house, a thousand to the taxman and I was left with £1,000.”

Although his works including The Longing and Suddenly One Summer have been incredibly popular, the artist has never quite won critical approval. But if there is disdain for his work from the art establishment then the feeling is mutual.

“I was very lucky,” he says. “My subject matter had never been seen before and there were folks in the establishment I offended greatly.

“Because I’m self-taught, the establishment can’t stand my work. Clearly the public do like it. My argument has never been that I’m good enough to be in the National Gallery.

“There was a poll asking people who their favourite Scottish artist was. Charles Rennie Mackintosh was rightly first. I was fifth, which is astonishing, I was delighted.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © David Sandison/The Independent/S

© David Sandison/The Independent/S © PA

© PA © PA

© PA