IT wouldn’t take a secret agent to spot a couple of very important dates this April and May.

On April 13, James Bond becomes 65, while the following month sees the 110th anniversary of the birth of Ian Fleming, the man who created 007.

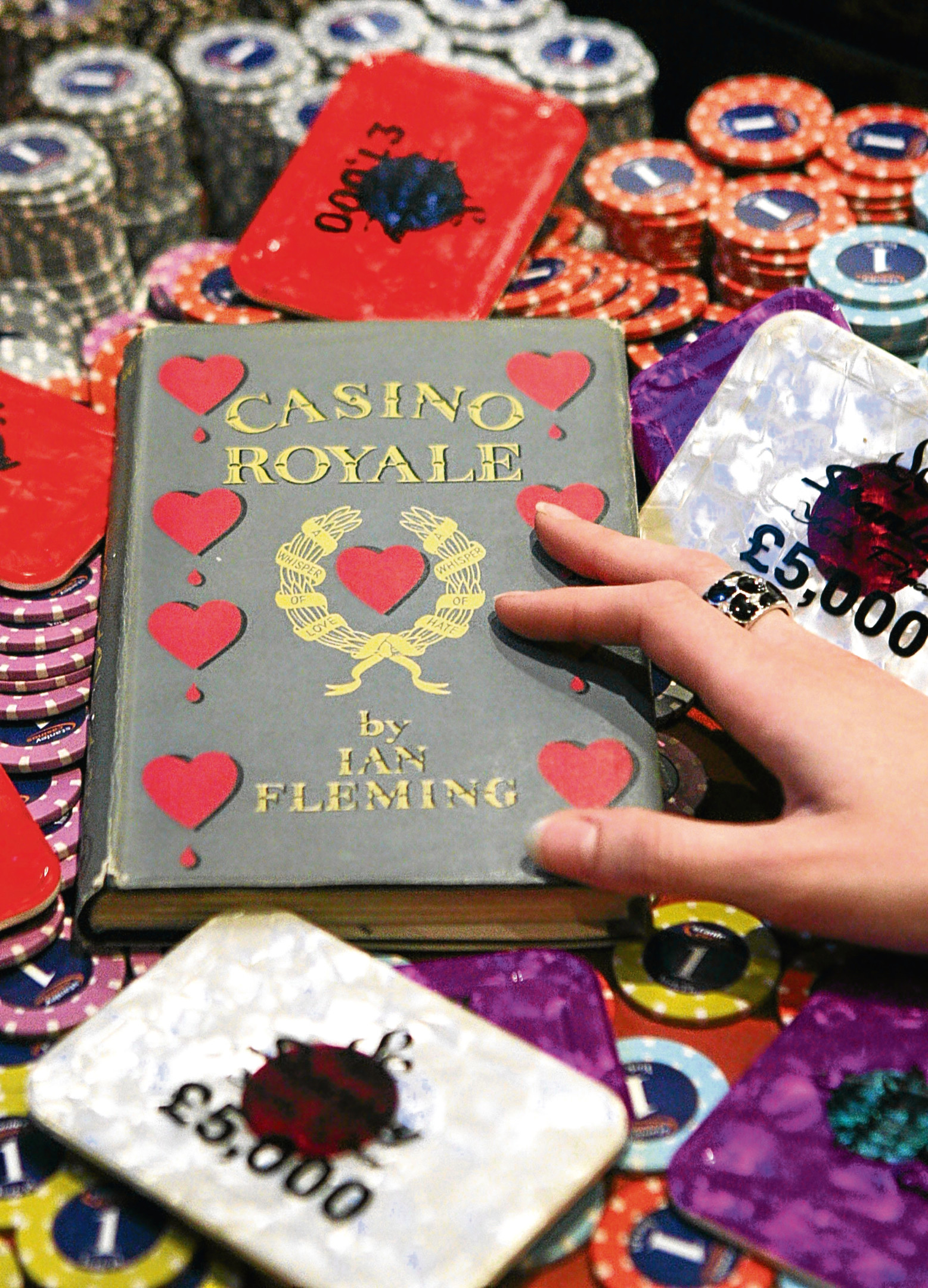

It was on April 13, 1953, that Casino Royale, Fleming’s first Bond book, was published, and it was on May 28, 1908, that Fleming was born in posh Mayfair.

Looking at Fleming’s life, you could be forgiven for thinking Bond’s action-packed existence was less exciting and eventful than his creator’s.

Following Casino Royale, Fleming would write a further 11 novels and two short-story collections, while other authors also wrote Bond-related tales.

Much of Fleming’s success was down to getting into a good habit and keeping in it.

Which meant his contract with a well-known newspaper publisher came in very handy.

He had it written into his deal that he could take three months’ holidays each winter, during which he left for his home, Goldeneye, on Jamaica.

It was here, overlooking a private beach and with a glamorous procession of stars coming and going that Fleming bashed out one book after another.

All, of course, would be turned into films, some more than once, and all would add to his considerable fame and wealth.

Fleming, though, was also a troubled man, dead by 56 after a life of over-indulgence in nicotine and alcohol, and with quite the reputation as a ladies’ man.

He also, of course, chipped in with the very un-Bondlike Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, published posthumously like two of his 007 novels.

His life, however, before taking up the typewriter was more about universities and wars.

Born to a Conservative MP father and wealthy socialite mother, Fleming had two little brothers and a half-sister.

At university, he often fell foul of the authorities for his lifestyle and womanising, wasn’t academically-gifted, but was good at athletics.

Removed from Eton and sent to Sandhurst’s famed Royal Military College, he ended up working with Naval Intelligence during the Second World War, which must have supplied much of his knowledge for the books to come.

With the Commandos, although he didn’t fight, Fleming did select targets and direct operations from the rear. Unlike the spy he would invent.

When he came to write that first book, Casino Royale, Fleming was unsure of its worth.

He sought reassurance from a novelist friend that it was worthy of publication, and was assured that it would do well.

Given pretty good reviews in the UK, it took longer to take off in the United States, but has since been adapted three times.

A 1954 episode of Climax, a CBS TV series, used the story, featuring an American Bond, while David Niven played “Sir” James Bond in the 1967 film version.

Daniel Craig played it straight as Bond in the most recent version, too, so not bad for a first attempt from a writer not at all sure of himself!

Live And Let Die, the follow-up published in April of ’54, had actually been completed before Casino Royale was even in the shops.

Based on Fleming’s intimate knowledge of London, America and Jamaica, it centred around Bond’s pursuit of Mr Big.

A horrid sort with links to Russian secret service SMERSH, voodoo and the USA, Mr Big has been smuggling old coins around the Caribbean, part of his bid to bring down the West.

It would become the eighth of the Eon Productions Bond movies, the first to star Roger Moore, and you’ll also find parts of it popping up in For Your Eyes Only and Licence To Kill.

And yet, while the book sold like hotcakes in Britain and required a second print run in its first year, the United States didn’t take to it at first.

It sold at a snail’s pace, a bit ironic when you think how well the movies would do. And you can’t blame Fleming’s writing. Named among the greatest English writers of his time, the books are even better than the movies for some!

Moonraker, again appearing in the April after more feverish writing at Goldeneye, featured a former Nazi now building sinister rockets for the Soviets.

Fleming, unlike most others of his time, knew how to take the Cold War paranoia and turn it into gripping fiction, just believable enough to make you keep turning the pages.

Diamonds Are Forever was inspired by Fleming reading about Sierra Leone’s diamond smugglers.

He somehow managed to get a chat with former MI5 boss Sir Percy Sillitoe, now working for a large diamond company, and Fleming always enjoyed travelling and making new acquaintances, especially if it led to more info and background details for his writing.

The writer also loved a routine, as many do, describing his working methods by revealing: “I write for about three hours in the morning, and I do another hour’s work between six and seven in the evening.

“I never correct anything and I never go back to see what I have written. By following my formula, you write 2,000 words a day.”

From Russia, With Love came next, followed by Dr No.

The first of this pair, he felt, might be the final James Bond novel.

Fleming told friends that he felt he’d written every spy-related tale he could, but then he always seemed to come up with fresh ideas for another.

This one was largely inspired by a visit to Turkey and a return home on the Orient Express, while Dr No became quite a contradiction — the first Fleming Bond novel roundly panned by the British press, it became the first Bond movie!

Sean Connery, needless to say, wasn’t quite the Hoagy Carmichael lookalike Fleming had envisaged, but the Scot didn’t do too badly as 007.

Goldfinger, For Your Eyes Only and Thunderball would all add to the grand collection of Fleming books.

Fleming had been tickled pink to learn that President John F Kennedy listed From Russia, With Love among his favourite books.

He had also found the woman of his dreams, too — he had disappointed Ann Charteris by telling her he wanted a bachelor’s life, and she instead married Viscount Rothermere, but they later divorced because she continued to see Fleming.

Together, they had a son, Caspar, the boy for whom he’d pen Chitty Chitty Bang Bang.

He might have been arrogant at times, and he was certainly self-destructive with his smoking and drinking, but Fleming was also a nice man.

Even when speaking to the ambulance drivers as they tried to save his life after another heart attack, he said: “I am sorry to trouble you, chaps. I don’t know how you get along so fast with the traffic on the roads these days.”

He died on August 12, 1964, and was buried in the churchyard at Sevenhampton, near Swindon.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe