We live in turbulent times yet the results of the election suggest little change. The turbulence operates alongside highly polarised politics. Debate on Scotland’s constitutional status has been intense and persistent ensuring that most minds are largely settled.

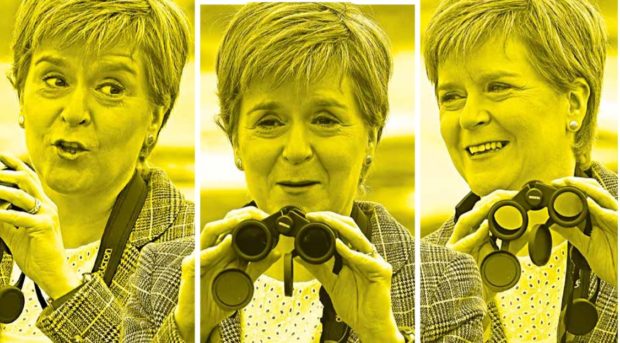

But the context in which these highly polarised arguments over an independence referendum take place is very much in flux. There may be little change in the overall composition of Holyrood but we are living through challenging times. The SNP under Nicola Sturgeon has successfully navigated these difficult times to emerge victorious once more. Incumbency has helped the SNP but that alone does not explain its success in winning a fourth term in a row.

It has been an extraordinary election, fought against the backdrop of a pandemic. Turnout is up, no doubt partly reflecting the sense that this was an important election. Only time will tell whether it proves to be have been historic but it will certainly be looked back on as significant. There is no doubt that debate on Scotland’s constitutional status remains high on the agenda. There was never any chance that this would change but the context in which that debate occurs is in flux and the claim to have a mandate is stronger than ever. It is this turbulence that will have to be navigated by the Scottish government while simultaneously arguing for a referendum. And that is not going to be easy. Tory leader Douglas Ross claimed you “just can’t” concentrate on recovery and independence in response to a question from STV’s Colin Mackay. The next five years will test whether he is right.

The first big shock that made governing much more challenging was the Great Recession over a decade ago. What started as a banking crisis quickly spread through the economy with massive consequences for public finances, public services and austerity. This shock still reverberates and will cast its shadow over the next five years.

Long gone are the days when “boom and bust” was assumed to have been conquered. The early years of devolution were marked by relative stability and significant growth in public spending. Public spending grew faster than at any time outside wartime but came to a crashing end. Economic growth and high levels of spending make tackling inequalities easier than in a period of retrenchment.

But all changed with the Great Recession. The economy faltered, businesses closed, jobs were lost, tax receipts fell, public debt grew. Cuts were imposed, mirroring earlier spending growth in scale. Tackling poverty is always an uphill struggle but the gradient became much steeper.

Economic growth is the least painful, if slow, way of reducing poverty but government action is also important. And the emphasis after 2010, under the Conservative-Lib Dem coalition, shifted away from reducing inequalities. There is now an added dimension that makes the state of the Scottish economy under devolution more important than before. With new powers have come new responsibilities. Under recent reforms, Holyrood is now responsible for raising a larger share of the money it spends. There is less reliance on grants from Westminster. And there is also more control of welfare payments. The ambition to provide a more progressive welfare network is welcome but it will not be easy to deliver.

The money available to the Scottish government depends on the state of the Scottish economy. Economic growth leads to more people working, paying more in taxes and more money available to the Scottish government. But the opposite is also true. The health of the Scottish economy will be key over the next five years.

The management of the Scottish economy is now much more important than it was in the early years of devolution. Our low business start-up rates, low levels of business investment, poor scaling-up of existing businesses and unimpressive record in educational attainment and skills need attention. Nobody should be under any illusion that this will be easy. Scotland has long struggled with these issues. Devolved government’s funding has been transformed from one that relied on the economic success of the UK as a whole to sustain high levels of spending to a system in which we now need to ensure that the Scottish economy improves its performance. Scotland may not be independent but it has a greater degree of autonomy than before. The lack of serious debate on the performance of the Scottish economy has been a remarkable and worrying feature of this election.

Three more recent shocks have contributed to the turbulence. The independence referendum, Brexit referendum and the pandemic will cast a long shadow over the next five years and beyond. Politics has been transformed and has not yet settled into a new pattern.

The referendums on Scottish independence and Brexit disrupted patterns of voting behaviour. Constitutional issues came to the fore and, when one issue comes forward on the political agenda, others are inevitably pushed back. Competition is not only between parties but amongst issues. Governments must prioritise, juggle time, resources and political capital.

Neither independence nor Brexit will return quietly into the background over the next five years. Independence is the driving idea for the SNP and it will remain the dominant issue in Holyrood regardless of whether a second independence referendum is conceded by London. Brexit will continue to take up considerable time and energy. Almost all estimates suggest that Brexit will have a significant and adverse impact on the economy.

But, beyond these shocks, there are many challenges ahead including deeply entrenched “wicked” problems – deprivation in its many forms and its dire consequences – that we have long struggled to address. When it comes to these problems, we should never underestimate politicians’ capacity for prevarication, kicking difficult issues into the long grass, going through the motions and the odd symbolic policy gesture. Crises often need to be knocking on our door before action is taken, or even acknowledged, as we have seen, for example, with climate change and drug deaths.

The pandemic demanded and received full attention but it will leave an unwanted legacy. There is no certainty regarding the pandemic’s impact, the prospects of recovery and lasting scars. This makes planning and preparation all the more difficult. Hidden problems will only surface over time. We do not know, for example, the long-term mental health impact of cooping people up, especially children, but have to assume this will have long-term consequences.

Families and individuals have had very different experiences that have been mercilessly exposed during the pandemic. This means, for example, we cannot assume that the loss of a “normal” school year has been the same experience for all. Access to technology makes a difference. Digital poverty is real, with many children and families lacking adequate internet access. It existed before the pandemic but was largely ignored, apart from the odd gesture.

The return to school will only hide the problem once again and make ambitions to close the educational attainment gap more difficult. The pandemic has exposed many problems and there is a danger that, as the pandemic recedes, so too will that exposure, while the problems remain.

One issue cruelly exposed by the pandemic, though it has long existed, has been the social care challenge. Our elderly population has been growing in absolute terms and relative to the total population. This brings opportunities and challenges. All too often we take for granted the enormous contribution that older people play in our families and communities. Anyone with even the most limited knowledge of our local communities throughout Scotland must be aware of the vital role retired people play in local community activities, not to mention the caring responsibilities within families.

A consensus has emerged around the need for action, and the idea of a National Care Service has attracted support. Part of the appeal to media-conscious politicians is that this sounds like the National Health Service, but there are various understandings of what this means. A neat slogan sold in an election needs to be translated into a complex policy.

A review of adult social care has helped ensure this will not slip off the agenda but has provoked criticisms from many in local government, though warmly welcomed by the voluntary sector. Be assured that this is now firmly on the agenda.

But the pandemic has also taught us to be more flexible. Whether we return to “normal” or take advantage of lessons learned will test whether the flexibility demonstrated during the crisis can be sustained with more home-working, less travel, opportunities that technology offers. But it will require much more than this. The resourcefulness of communities supported by local government has delivered in ways that the Scottish government simply could not do on its own.

The lesson that ought to be learned is that empowering communities necessitates empowering local government and that hoarding power at the centre needs to end. The easy option would be to create a Scottish equivalent of former prime minister David Cameron’s failed “Big Society” programme, disempowering local bodies under the pretence of empowering communities.

Dumping problems on our communities, forcing poorer people to make unpalatable decisions that politicians in Holyrood will not make, is disempowering. This will be a major issue over the next five years.

Will we slip back into old ways with blame games? Or will Holyrood take responsibility, share power and resources in a way that will benefit our communities? Slipping back into old ways is the easy option. As the SNP stated in its manifesto: “The pandemic showed us that when there is a strong enough will we can make rapid change in a very short period of time.” We will see whether the same strong will exists to tackle Scotland’s other challenges, including many deeply entrenched problems.

Big challenges usually require difficult, even unpopular, decisions. There are many welcome promises in the SNP manifesto.

The manifesto lists many pots of money and various strategies designed in many cases to be seen to be doing something without seriously tackling inequalities. The current council tax freeze is a classic example of putting electoral popularity ahead of good policy making.

The freeze undermines local autonomy, redistributes wealth in favour of the well-off and limits the resources available to local government to provide services. That does not speak of the strong will referred to by the SNP in its manifesto. We should be grateful that there is evidence of long-term thinking. Politicians tend to operate hand-to-mouth, thinking from one election to the next, if not day-to-day. This undermines long-term planning difficult. But it is unrealistic to expect transformation in all outcomes within one parliament.

And, while we might be cynical about SNP commitments – such as building 100,000 more homes by 2030; decarbonising the heating of a million homes by 2030; creating a smoke-free Scotland by 2034; halving childhood obesity by 2030; becoming a net-zero nation by 2045 and much else besides – we should applaud this evidence of long-term planning. Notably, these long-term commitments are matters on where there is broad cross-party support so that we should expect continuity if there were a change of first minister or government in Holyrood.

It is easy to commit to something that you leave to others to deliver by a date in the future. But providing evidence of progress along the way will undermine cynicism. We should also recognise that no journey in tackling deep-rooted problems will be smooth.

Mistakes will be made, progress may feel slow at times, but persistence, commitments and proper resourcing will get us where we need to be.

James Mitchell is professor of politics and international relations, University of Edinburgh

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Lesley Martin / PA

© Lesley Martin / PA