For the first 30 years of her life, Ali Millar believed the end of the world was coming.

Caught up in a constant cycle of fear, concern, terror and guilt, she had been conditioned to believe loved ones, friends, teachers – anyone who wasn’t a Jehovah’s Witness like her and her family – would soon be dead.

Living in unrelenting dread of Armageddon was not without its consequences. Millar suffered anxiety-induced stomach cramps and migraines as a child, became anorexic in her teens and, when she was ostracised from the organisation when she was 29, teetered on the brink as she contended with PTSD, depression, insomnia and, when she did sleep, terrifying, sweat-inducing nightmares.

It was only her love of writing, which she calls her safe space, that helped her through that first year when she found herself alone and learning how to live in the outside world for the first time.

Now 42, living happily with her partner, and mum to four children, Millar has finally wrestled control of her life but as a result has lost her mum and sister, who remain devoutly loyal to the Kingdom Hall. She has written a book, The Last Days, a riveting, lyrical but harrowing memoir about growing up in the Borders under the control of the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

“Writing the book felt like a way of finding how to speak and then I learned to roar,” said Millar, speaking from her home in London. “Writing the book was really painful as I had to go back into the past but it also helped me make sense of that period as well. It helped me to understand my mother better – who I had been grieving for and was really upset about – and as I wrote it, I could work out what was done to her. It helped me make sense of what happened and that means I can now sleep and not have the same nightmare. It helped propel me forward to where I am now.”

Millar was just a few months old when her mother, feeling vulnerable after discovering her new baby’s father was a married man who had multiple children by different women, allowed the Jehovah’s Witnesses who came to her door not only into her house but into her life.

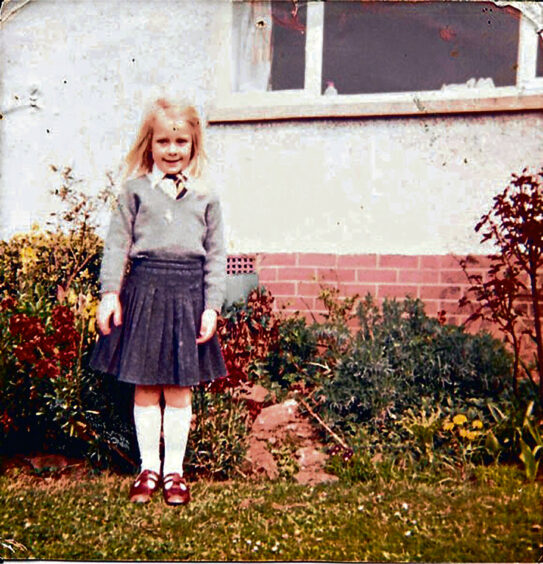

“I was a really devout child but at the same time I wanted to be normal, to celebrate Christmas and birthdays but I was told these were wrong and sinful practices,” Millar explained. “I thought there was something wrong with me rather than what I was being told. That created a lot of internalised grappling and I took that out on myself instead of voicing the questions I had, because any dissent is discouraged.

“A lot of it is unpalatable. I was supposed to tell my friends about the end coming. I found that very difficult, thinking people at school were going to be destroyed because their parents were non-believers. Little things like that ate away at me and I was not a well child. That was an anxiety about the end coming.

“I would go to school and worry about what would happen if the end came while I was there, how I would get home because there would be no bus driver – silly things that are huge things as a child. When I became a teenager and started experimenting with alcohol and boys, that brought on guilt and I became obsessed with cleansing myself, which is where anorexia came in.”

It was both a blessing and a curse for Millar to still have contact with the outside world. Unlike many Witness children who are tutored at home, Millar was sent to school. Contact remained with her grandparents, too, as Millar’s mother, as a single mum of two, remained dependent on them.

“My grandparents were a lifeline and when I was at their house it offered a window into another world and a different way of being and that was wonderful. But I used to really worry about the end coming because I knew they would be destroyed. My granny was a doctor, she was a very intelligent and fierce woman, so having that role model has shaped me in many ways and I’m so fortunate I had her.

“School, too, was a useful way of seeing other ways of living but it also created conflict because I felt they weren’t open to me. Having an education was vital, though.”

Millar says her grandparents reached an uneasy peace where religion wasn’t spoken about.

“I don’t think they knew the extent to which the religion pervaded every aspect of our lives and how it limited our future. It has a public face and a very different private face. I think my grandparents thought it more about we didn’t get to celebrate Christmas or birthdays. It can be hard for family on the outside to understand what goes on and the pressure people face,” said Millar, pointing to issues such as the refusal of taking blood transfusions or having abortions.

Despite her ongoing internal conflict, Millar devoted herself to the organisation, married a fellow Witness and had a child but when their relationship ended in divorce, she found herself on the fringes and seemingly with few options.

“I was never asked to leave but I was ostracised by the congregation. I began going to meetings less and hadn’t been seeing other people but I was terrified to leave because I’d been so devout and I also didn’t have a support network on the outside and I had a young child,” she said. “You were warned that if you left, your life would become a complete mess – you’re told you will turn to drink or drugs, and everything will be horrific.

“The talk was that divorced people would never be accepted by God, so I thought, ‘Why am I trying to bend over backwards for this approval that I’ll never get because I’ve been divorced?’ There was about a year after I left where I was absolutely terrified. I didn’t know anyone. I didn’t know myself.”

Millar would like to see the authorities look into the organisation and believes a linked method is required.

“There is no joined-up approach across service providers to safeguarding issues,” she continued. “Health care, police, education, there has to be a joint approach. Vulnerable children shouldn’t be subjected to uncomfortable beliefs. There shouldn’t be penalties for leaving a religion. You shouldn’t have to lose everybody and struggle to join a society you don’t understand.”

Millar met someone outside of the church who worked in music and they have three children together. She continued to follow her passion for writing and studied a creative writing course at Napier University in Edinburgh. She has worked as a cultural producer for Summerhall in the capital and has chaired events at the Book Festival.

She hasn’t told her youngest children – aged nine, eight and five – about her past but her 19-year-old daughter is old enough to remember.

“For now I want to keep them innocent and protect them from the idea that people believe the end is coming but when they’re older I’m sure we’ll talk about it, about my childhood and my daughter’s,” she said. “I saw the negative effects it had on her. She had nightmares, too, and I want to keep them free of that.”

That her mum and older sister are lost to her is something Millar has had to concede. Her mother cut her out of her life with an 83-word email after she heard she’d been writing “derogatory comments about Jehovah”.

“I wouldn’t say I’ve come to terms with it as it’s a grief and grief doesn’t go away but realising that people can be manipulated into doing terrible, senseless things because they think it’s the right thing to do helps me deal with it and it’s how I reason it out mentally,” she said.

When Millar built her new life over the past decade, she struggled to tell new friends about her past, so there has been surprise over the book. She began writing it three years ago but it had been in her head much longer. At first, she wanted to keep herself out of it and write something hard hitting.

“But I realised the personal aspect was a good way of bringing people in and I knew something that people outside of the organisation didn’t know about, so it felt like a necessary story to tell,” she explained.

“I’m worried about how it could be received and seen but I don’t want to create a personal attack on the members in any way, because I think they are manipulated and controlled. I really didn’t want to tell the reader what to think; I just wanted to tell what happened and if they come off looking bad, it’s indicative of the way the organisation works.

“I have nothing against religion or them existing as a religion, but I want it to be a religion that isn’t doing harm to its members.”

From the book: Someone has stolen my voice. I want to disappear

Ali Millar, due to have her tonsils removed and watched by a Jehovah’s Witness elder, tells a doctor she’d refuse a transfusion

I know that, if something goes wrong and I need a blood transfusion, the doctors will try to get a court order. The courts are less likely to intervene if I’ve said I don’t want blood. That’s why it’s important I speak now. But someone has stolen my voice. I want to disappear. The doctor looks at me. I know he expects me to at least look at him too. I raise my eyes to meet his. I open them wide and stare at him so he knows I mean it when I say, I don’t want a blood transfusion.

The elder smiles, and I’m sure Mum does too.

Why? the doctor asks. I recite the scripture in Leviticus, telling him we’re bound by it. He says, I thought Jesus did away with the Mosaic Law. I don’t know what I’m meant to say now. The elder steps in. He says, “As true Christians we’re bound by both the Old and New Testaments.” I nod. The doctor raises one eyebrow. I wish I knew how to do that. Then he sits back in his chair and looks at me like he’s never seen me before. You’ll have to sign these forms, he says, pushing them over to me. I sign with the signature I’ve practised, and Mum does too. The elder doesn’t sign.

When we get up to leave, the elder reaches out to shake the doctor’s hand as if he’s done some kind of deal, but the doctor moves his away and gestures to the door. As we walk down the corridor Mum puts her hand on the back of my neck and sort of steers me along the way she does sometimes. I think maybe she’s trying to tell me I’ve done very well.

The Last Days by Ali Millar is published by Ebury Press

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe