Monday will witness ceremonial on a scale seldom seen in the world.

The last state funeral in Britain, of Sir Winston Churchill in 1965, is outwith the memory of most. So whatever your views on royalty, the spectacular send-off for Her Majesty will be a historic event.

Yet no one can forget the mourning began here in Scotland. Queen Elizabeth’s former press secretary, Michael Shea, a Scot, once wrote a book called The Primacy Effect, which argued that the first few moments of an encounter shape the relationship forever. Scotland’s Primacy Effect was undeniable last week.

From the silent crowds in Edinburgh’s High Street, the solemn, fresh faces of the Royal Regiment of Scotland pallbearers, to Karen Matheson’s Gaelic rendition of Psalm 118, Scotland made a striking first impression while the world watched.

Edinburgh never looked more beautiful, with austere St Giles’, draped in saltires and lion ramparts, providing a medieval setting to rival Westminster Hall.

The exhausting round of vigils, processions, speeches and handshaking has been methodically planned, with the new King’s approval. It has purpose.

The palace planners have been clever in linking acceptance of the new King, and the monarchy generally, to the extended farewells for his much-loved mother.

Much of what we saw last week was quite new. The Vigil of the Princes, for example, only began in 1936 and was done in private. Even the ceremony we will witness tomorrow dates largely from Queen Victoria’s state funeral in 1901.

“There’s nothing so easy to invent as a tradition,” said Sir Walter Scott, who stage-managed the 1822 official visit of George IV to Edinburgh. There were fears lingering Jacobite sympathies could mean a cool reception for the Hanoverian, so Scott set about creating a spectacular display. He designed everything from the tartan to the eagle feathers sported by The Royal Company of Archers. He even put the king in a kilt – a “tradition” his descendants still follow when visiting Scotland.

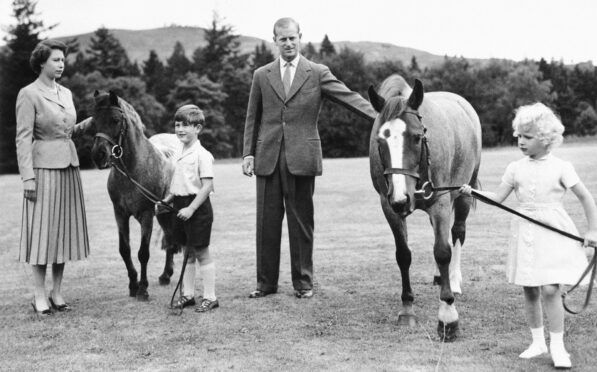

Queen Elizabeth also knew the importance of public ceremony in cementing the monarchy’s position, not just in Scotland. She was unassuming in private, but once said: “I have to be seen to be believed.”

Commentators have been quick to suggest the palace’s decision to put the nations of Scotland and Wales, as well as Northern Ireland, at the centre of mourning activity, reflects concerns about independence. Some even believe Scotland’s respectful display is an endorsement of the Union itself. That misunderstands our historic relationship with the monarchy – there was a union of crowns for 100 years before there was a union of parliaments.

Charles may also be learning from his mother’s response to the crumbling British Empire of the 1950s. She held her “dominions” close and the Commonwealth became one of her great achievements. Events today are different – Scotland is not and never was a colony – but the past still offers useful lessons.

Charles last week recognised Scotland as a nation – his words underpinned by those displays of tradition.

Meanwhile, the UK Government says Westminster should ignore the Scottish Parliament. Briefings from those close to Liz Truss insist UK ministers should stop referring to the UK as a family of distinct equal nations, and start emphasising the unitary British state instead.

The monarchy seems to have rejected that approach. The Crown uses soft power to flatter us, while politicians retreat into muscular unionism. It will be fascinating to see which approach has more success.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe