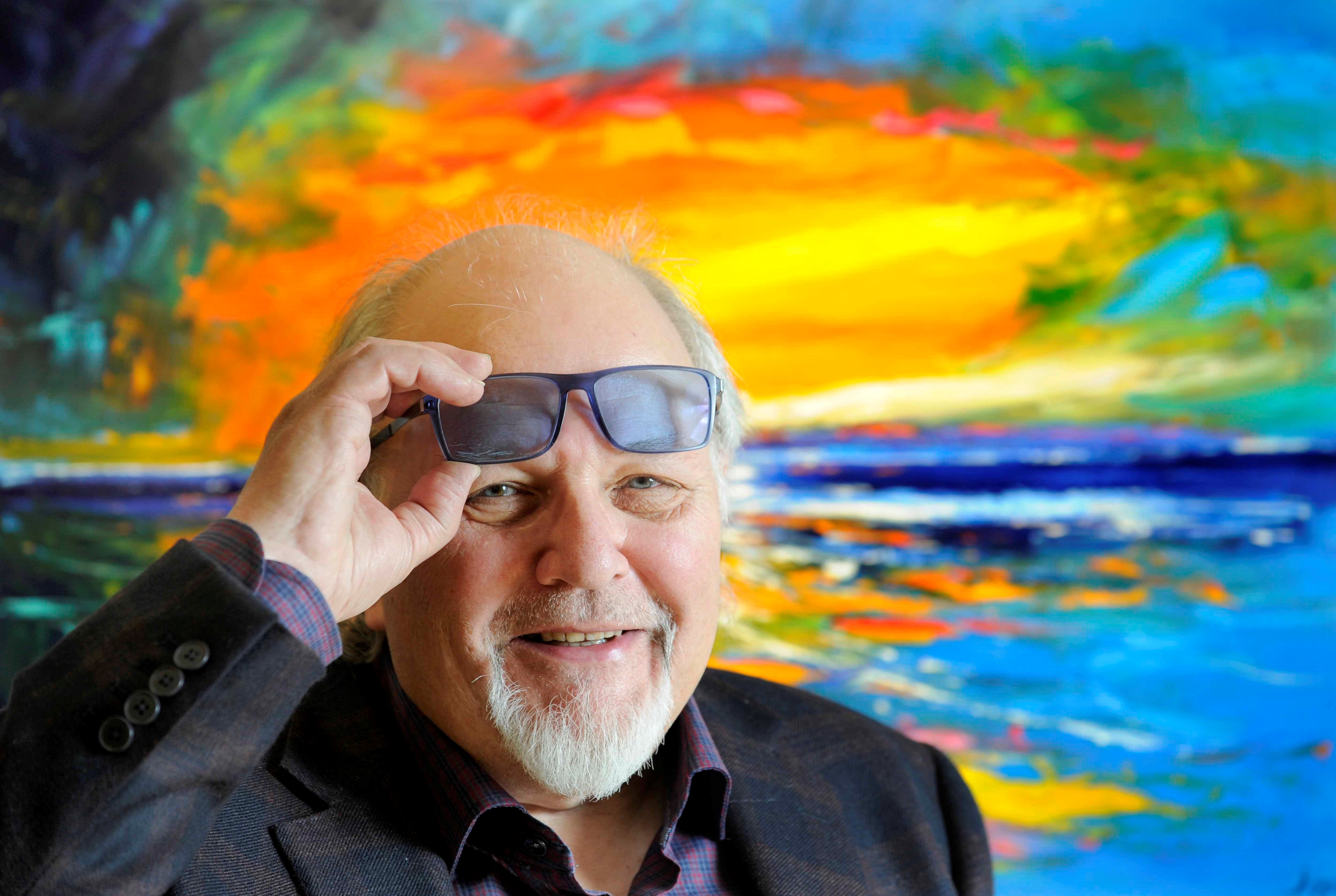

Azure skies sweeping behind a red-roofed croft nestled in bright foliage. Silhouetted islands dappled in the rays of an ochre sunset. Instantly recognisable, the art of John Lowrie Morrison is acclaimed around the world.

More commonly known as Jolomo, his work is unmistakable. His vivid, expressive depictions of his beloved Argyll and the Inner and Outer Hebrides can be found on prints, mugs, postcards and calendars in shops across the country.

But the artist is refusing to slow his prolific work rate and a new collection sees Morrison’s gaze switch from west to east, as he exhibits the beauty of Angus in a new group of paintings at Dundee’s Gallery Q.

Towards the Light – Argyll and Angus, focuses on the differences between the landscapes, light and colours of Scotland’s west and east coasts.

Also a lay preacher for the Church of Scotland, Morrison was entranced by the light of the glens of Angus on a drive back to his Lochgilphead home, which he shares with his wife, Maureen. He had been conducting a sermon for the Queen in Crathie Kirk last July while she was in residence at Balmoral Castle.

“On the drive from east to west, I decided to go the quieter way down over Braemar and Glenshee and turn off the hill towards Pitlochry – down through Glen Clova – and I couldn’t believe it, it was just wonderful. I hadn’t a clue that it was so beautiful there,” he said.

“I found that the east coast light is far softer than the west, with a kind of greeny and lemony colour so I’ve painted it like that. I could’ve painted those scenes forever.”

Non-stop is indeed how Morrison, 70, likes to work, often creating he says, up to two paintings in a day, mainly from the photographs and sketches of scenes he’s captured around the country.

“I start work around 7.30am and paint until about 3.30pm. And because of the expressive nature of what I do, it never takes too long to create a painting.”

It’s just as well as Morrison’s exhibitions are renowned as sell-outs with stars like Sting, Madonna, Simon Le Bon, Sophia Loren and Rick Stein among his fans.

But it wasn’t always like this.

Morrison worked as an art teacher in Lochgilphead for nearly 30 years, before becoming a full-time artist in 1996 in his mid-forties.

Growing up in a Maryhill tenement in Glasgow’s north-east, his first artistic experience came at the age of two during a bath in the kitchen sink, drawing with his finger on the steamed up window. Aged eight, he’d already made up his mind he wanted to go to Glasgow School of Art, originally to study fashion design.

“I used to secretly buy Jackie magazines, and I would copy the way they did their figures and then I started doing my own stuff – nobody knows that though!”

His love for Argyll and the west of Scotland came from his parents and family – with roots on Harris that he says trace back hundreds of years.

“My mum and dad were big bikers back in the 1930s. They had a tandem, and they used to cycle all the way from Maryhill to Oban and often even beyond that to Ardnamurchan, where my family now have a second home and studio,” he muses.

“I’ve always, ever since I was a wee boy, wanted to stay in Argyll and then that’s translated into my art.”

So too has his work as a minister, says Morrison, who believes art and spirituality are intrinsically linked.

“A lot of people have a spiritual psyche or whatever you want to call it, and I think it’s very much the same with me. The paintings I do are really to do with beauty – I try to paint with a balance of colour, a balance of composition and a balance of texture and it gives a real feeling of stillness,” he says.

“A lot of hospitals and hospices get hold of my work for that reason. I had a lovely email from a young mum who was sitting in Ninewells waiting room and her wee boy was really ill. But she said sitting looking at my prints really lifted her up. It’s that connection that I like with people. You’re creating something beautiful that goes into their soul.”

His philanthropic ethos has also touched children in Scotland as well as aspiring artists.

In 2016, he designed one of the Oor Wullie statues which made up the hugely popular bucket trail around Tayside, in aid of children’s charity, the Archie Foundation.

His creation, Jolomo Oor Wullie sold for £15,000 and was later put on display at Perth Royal Infirmary.

In 2006, he founded the £35,000 Jolomo Award, the largest art prize in Scotland, aimed at emerging artists painting the Scottish landscape.

But reaching such eminence can come at a cost. With an estimated annual turnover of £2million a year, his works have become so lucrative that his rivals are now not other artists, but ‘copyists’. Companies are simply copying his paintings and passing them off as Jolomos.

“There are hundreds and hundreds of Jolomo copyists just re-hashing the exact colours and techniques I use or painting red roofed crofts,” he says.

“It frightens me to think there’s a company somewhere in the middle of China doing it and selling it.

“There’s this company who do pastiches of my work, they don’t put Jolomo on it, but they put other similar names on it. They’re just ripping me off.”

Morrison continues to be one of the best-selling artists in Scotland.

“I’m still selling art hand-over-fist. And I guess, as my family keep telling me, when it comes to the copyists, I shouldn’t be too annoyed. It’s really the highest form of flattery.”

John Lowrie Morrison: Towards the Light – Argyll and Angus, Gallery Q, Dundee, until April 13.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe