Kate Mosse is in the Lake District, thinking about two members of her family who she has only just gotten to know: her great-grandmother Lily, and her first grandson.

For an author who has sold more than five million books, in 42 languages, all the success and critical acclaim in the world pales in comparison to the cherished times when she holds her seven-week-old grandson.

“It’s completely wonderful. In a very busy, and rather challenging world at the moment, there is nothing quite so peaceful as holding a baby in your arms,” said Mosse of the early mornings when she bottle-feeds her grandson to allow her daughter Martha and partner Ollie a chance to catch up on sleep.

“When you have a new baby of your own, you’re freaked out and can’t believe they’ve let you take them home from the hospital. Whereas, when you’ve done it all before, it’s just joyous.”

When we speak, Mosse, who celebrated her 61st birthday earlier this month, is on tour to promote her latest non-fiction title, Warrior Queens And Quiet Revolutionaries: How Women Also Built The World, which celebrates extraordinary women from around the globe and across the centuries whose achievements, endeavours, inventions and lives were erased from history.

The idea for the alternative history began as a question posed to Mosse’s followers on Twitter during lockdown in 2021. “I asked people to tell me one woman from history they wished was better known and received thousands of replies. It’s the only time I’ve ever trended on Twitter apart from mistakenly as the other Kate Moss!” she recalled.

“I found out about so many incredible women and thought, why aren’t they household names? That got me asking, what is history? Who decides who matters and who doesn’t? And why are women so routinely left out of the history books?”

The answer to that last question, noted Mosse, was: “Because men were writing the histories. It’s as simple as that.”

Curious to uncover more, Mosse spent the UK’s third lockdown at her home near Chichester in West Sussex, where she lives with her husband Greg and 92-year-old mother-in-law Rosie, rewriting the legacies of trail-blazing and inspirational women.

That includes the Edinburgh Seven, the first women to study medicine at a British university. A riot broke out when the women turned up to sit an anatomy exam at Edinburgh University in 1870.

“This was a story that is fundamental to the history of women and medicine,” said Mosse. “Those seven brave women, including suffragette Sophia Jex-Blake, made a stand just to be allowed to be doctors, to help people. They were pelted with mud and faced vile misogyny and persecution but rather than driving women out of medicine, the backlash against the men’s actions changed people’s minds about women being doctors.”

Learning more about one woman in particular, a gifted writer whose literary achievements had faded from history, had a profound effect on Mosse – it was the story of her great-gran, Lily Watson.

“I discovered my great-grandmother had been a well-known novelist in her day. Yet she’s disappeared from historical records, you won’t find her name in any books and her works are out of print,” said Mosse.

“I knew there was someone in my family who had written but I didn’t realise she was celebrated in her time. When she published her most popular novel, The Vicar Of Langthwaite, in 1893, Prime Minister William Gladstone wrote a letter praising it to The Times. She also had six children, three of whom had haemophilia, and her youngest son died when he was 12, so she wrote her novels during enormous tragedy and grief which is extraordinary.

“Reading Lily’s journalism, I suspect we would not have seen eye-to-eye on many political and social issues. Much of her work has a Victorian moralising idea of defined roles for men and women. Yet she had this huge reputation in her time but that is now gone, which is the case with many other women, famous in their day but later lost from history. Perhaps only ‘the Matilda Effect’ can explain why she has disappeared from history.”

The Matilda Effect, explained Mosse, was “the bias against acknowledging the achievements of female scientists whose work has been misattributed to their male colleagues.”

Lily’s story forms the spine of Warrior Queens And Quiet Revolutionaries, as Mosse turns detective to tease out details of her ancestor, who lived from 1849 to 1932.

“Lily was proud of what she did, she believed in the power of words,” said Mosse. “What’s funny was discovering that one of her six children, Winnie, wrote under a pen name, Pamela Wynne, and was considered a really racy novelist. I don’t think my great-grandmother approved but Winnie wrote around 60 novels and has an entry on Wikipedia, but her mother doesn’t.

“It’s about whose reputation endures and that’s so important because women were always here, we’ve always made the world with men in every field; invention, exploration, science, medicine and faith but we’re not there in the books. We need to change this.”

It was important for Mosse to celebrate the achievements of women rather than lament their erasure. “I’m a quiet revolutionary, not a warrior queen,” she admitted. “It’s better to be hopeful about changing things than getting furious about the past. That’s why I see this book as a starting point for a conversation. It’s encouraging to see young people engaging with the book, which is great news for an old feminist like me.”

During lockdown Mosse helped her husband care for another important woman in her life – her grandmother-in-law Rosemary, whom she affectionately calls Granny Rosie. While she was able to juggle spending time with Rosie and writing, it opened her eyes to the challenges faced by carers.

“Women have a 50/50 chance of being a carer by the age of 49. Many are therefore having this huge shift in their lives at exactly the moment their bodies are shifting in a very significant way during the menopause,” said Mosse.

“I’ve been a carer for 14 years, my father died in 2011 and my mother died in 2014 at Christmas. All of these things, including grief, were all wrapped up together. It was hard to know what emotion you were feeling.”

Mosse is thankful her own success as a writer came later in life. “I was an overnight success at 45 and that’s great as it means you don’t take it for granted. You don’t get used to it. There are so many wonderful books so it is luck if the spotlight shines on you.”

She hopes that spotlight will be cast over her husband Greg, who publishes his debut novel, The Coming Darkness, next month, and her son, Felix, who will do the same next year.

Mosse hopes to see her great-gran’s work back in print: “I’m trying to get my publisher to republish The Vicar Of Langthwaite. She deserves it, they’re great novels.”

Mosse also uncovered a detail about Lily that connected directly to her Burning Chambers series centred on the Huguenots, a religious group of Protestants driven from France in the 17th Century. “I discovered Lily’s grandmother was a Huguenot, which was mind-blowing as I’m writing historical adventure novels that follow a Huguenot family. It’s something I’ll look into further.”

For now, she is continuing the family legacy with a new book inspired, in part, by her great-grandmother and other, albeit more brutal and buccaneering, women left on the peripheries of history.

“At the heart of all of my fiction are unheard and under-heard women’s stories set against the backdrop of history,” she said.

“I’m working on the next instalment of the Burning Chambers series, The Ghost Ship, about women pirates, which comes out next July. There were a number of women who disguised themselves as boys and men and went to sea, and as my Joubert descendants will travel by sea, I saw a story there. And, not least of all, because Lily loved pirate stories.”

Go-to Gothic writers

Kate Mosse has harboured a love of Gothic thrillers from a young age and explored the genre in her best-selling Gothic fiction, The Winter Ghosts (2009) and The Taxidermist’s Daughter (2014).

Mosse said: “For me, writing Gothic fiction is a treat. Whereas my historical fiction is very much putting women’s history back on the page. The Gothic fiction is having a bit of fun.”

In Warrior Queens And Quiet Revolutionaries, Mosse highlights the work of female writers who were pioneers of Gothic fiction, like Ann Radcliffe (The Mysteries Of Udolpho published in 1794).

“Ann Radcliffe was a superstar in her day and is seen in a way as creating that genre.

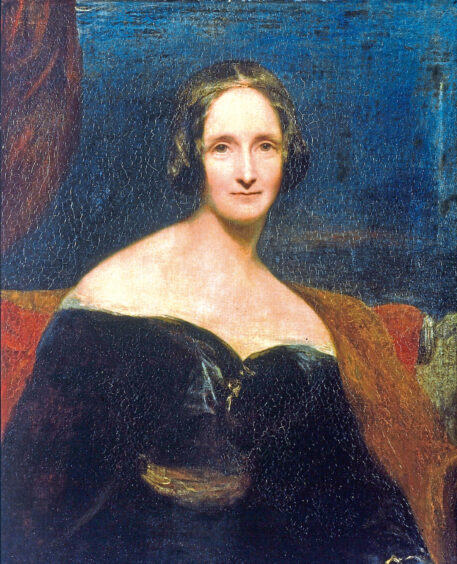

“I also included Mary Shelley because, while everyone knows Frankenstein (1818), not everyone appreciates how much influence the novel had on all of writing.

“And there’s Margaret Cavendish, who you could say invented the genre of science fiction as her books (notably The Blazing World, 1666) blended science fiction and Gothic fiction.

“These writers all had a profound influence on English literature but are not seen as important as male writers of that period like Charles Dickens and William Thackery.”

Warrior Queens And Quiet Revolutionaries, published by Pan Macmillan, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© PA

© PA