Ken Loach has been making game-changing films for almost 60 years.

But, even though he turned 87 earlier this summer and is about to release a movie that may well be his last, the legendary director has admitted he loves his work so much he couldn’t ever entirely rule out returning behind the camera.

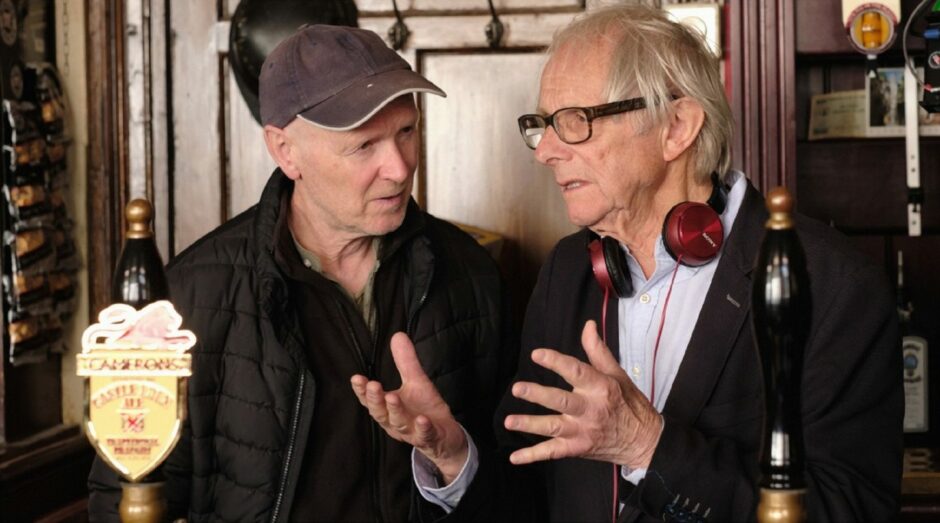

Loach has teamed up with Scottish writer Paul Laverty for new film The Old Oak, about people in a dying mining community who struggle to cope with the arrival of refugees from the Syrian civil war.

The Midlands-born filmmaker first came to prominence with the 1966 homeless-themed drama Cathy Come Home, and made headlines with equally hard-hitting stories from My Name is Joe to I, Daniel Blake and Sorry We Missed You.

Loach said he would find it hard to give up making films like these, but he hasn’t got anything lined up after The Old Oak.

“There is nothing on the cards at the moment – it’s difficult to see us going around the course again, to be honest,” he admitted. “But you never know. There’s always a twinkle in the eye. It’s a hard job to give up.”

Loach, who has been tipped to retire after almost every film he has made in the past decade, said he keeps coming back to stories he feels need to be told.

Having made his last two films in the north-east of England, about welfare justice and zero-hour contracts, he said he wanted to round off the trilogy by looking at the decline of the region’s proud industrial past.

The Old Oak

The Old Oak, the 14th film Loach has made with Laverty, is about a small town in County Durham struggling in the years since the closure of the local mine, and now facing a new challenge of arriving Syrian refugees.

He said: “There was no choice, this was a story we had to tell. One element we hadn’t looked at in that area was the way old industries had gone and the desolation left in their wake – this was most clear in the villages in County Durham.

“When the mine shuts, the community that had been so strong is left to rot. People have left, houses are cheap, the shops are closing, public spaces have gone – they’ve been abandoned.

“For us, it’s asking what is the story, and Paul had the idea to tell the story of when the Syrians first arrived and how they were first treated – they had a mixed reception.

“They’d suffered the trauma of war and had often lost family members. Children were traumatised and brought to an area where they didn’t speak the language, so it was looking at how can the two communities could live together.”

Laverty said: “It was very much an idea that we’ve been interested in for a long time. And it goes back again to what those miner communities were like before the 1984 strike. You can see the disintegration. In these communities now, a house will be bought online on a Monday and sold online again on a Friday, because it’s cheap.

“And then you add in the whole question of another traumatised community. The Syrians who had experienced unbelievable cruelty and were then being demonised and scapegoated, the same way people on welfare were being scapegoated in I, Daniel Blake.

“We felt there were lots of things to try to tie up, so there was a big, big canvas on this one.”

Casting

In keeping with their track record of filling their cast with people from the communities they film in, Loach and his team worked for months to find locals for the roles. Its lead star Dave Turner is a retired firefighter.

But the most crucial element of the real-people casting was the recruitment of the real-life Syrians who had been resettled in County Durham just a few years earlier.

Loach said it was vital to get that sense of authenticity. He said: “The camera sees who you are really, if you’re a film star or working man or working woman, it’s everything about you. What we’ve always tried to do is to be accurate, to be authentic, as far as one can.

“We listened to the stories of people who had been through the most appalling torture, stories of families going through checkpoints and being within seconds of being shot dead until a guard had a phone call at the last minute.

“The lad who plays the eldest son of the main family has a shrapnel wound in his head that he carries to this day. They’ve all lost family members. One woman had lost her whole family. There’s so many terrible stories. They knew this world, they lived it and they reveal it in the film.”

Laverty added: “Many people we spoke to couldn’t give their names because they didn’t want to put their families in jeopardy.

“When it’s not your culture or language, the least you can do is have a great respect, and listen and understand. We spoke to many people through organisations in Scotland.

“Spending time with these people and hearing their stories was so key to making this film.”

Still going strong after three decades and many plaudits

In 1996, Ken Loach recruited a first-time writer for an incredible adventure that took them all the way to the heat of Central America.

But when they first met to discuss a project which would become the smash hit Robert Carlyle film Carla’s Song, neither Loach nor Scots writer Paul Laverty would have guessed they would still be making films together three decades later.

Since then, the duo have made 14 films, been lauded at Cannes and the Baftas and been credited for helping raise awareness of all kinds of social-justice issues, from benefits sanctions to addiction, violence and zero hours contracts.

Paul, a former lawyer, first wrote to Ken in the early 1990s to discuss an idea for a film.

As Ken recalled: “I got a nice letter from a bloke who had been in Nicaragua working as a human rights observer chronicling the atrocities, so I was immediately interested.

“I’ve always been on the lookout for people with something to say, so we met and had a coffee. We got off to a good start. We see the world in the same way and we put up with each other’s foibles.”

He added: “Of course you never know how things will turn out – you take it one game at a time.”

Since then, the pair helped Peter Mullan win a Cannes Best Actor Award, launched the career of Scots star Martin Compston, and lifted two Cannes Palme d’Or awards, while their agenda-setting benefits drama I, Daniel Blake won Best British Film at the Baftas.

Paul said: “What I love about Ken is his curiosity. It was a treat to get the first film done, and for all I knew, that was it.”

In fact, the first time Paul realised he was embarking on a new career was when the whole crew of Carla’s Song were hit by terrible illness in Nicaragua.

He recalled: “Everybody got ill apart from me because I already had all the bugs from previous trips.

“We had talked about making (LA-set) Bread and Roses but Ken was wrecked after this shoot. Just as I was saying goodbye to him on the plane he said: ‘Let’s try to come up with a story closer to home, why don’t you just think about a wee story in Glasgow.’

“And I’m just like: ‘Wow, I’ll get to do another one’, because I’d never presumed I would. That’s where My Name is Joe came from and with luck, one story has just bled into another.”

The Old Oak is in cinemas from September 29. Ken Loach and Paul Laverty will introduce a special preview of The Old Oak at Glasgow Film Theatre, Wednesday, 6.50pm.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Sixteen Oak / Why Not Productions

© Sixteen Oak / Why Not Productions © Joss Barratt, Sixteen Films

© Joss Barratt, Sixteen Films