The downsides of the Covid-19 crisis are everywhere but there are upsides too. Smaller, perhaps, and harder to see but there are the small acts of kindness, one human reaching out to another in ways they might not have done, had it not been for these awful times.

This one began with an article I wrote before The Queen addressed the nation recently when, despite being a lifelong republican, I argued how it was possible to view her as perhaps the most remarkable person alive.

I listed, and explained, the qualities that led me to that judgment: longevity in the same role; enduring excellence; universal fame; humility; good in a crisis; resilience; humanity; humour; mystique; and, above all, her sense of duty.

I recalled my first political row, aged six or seven, was when my mother said I had to sit with her and the rest of the family to watch the Queen’s traditional Christmas message.

“Why?” I protested. “Why should I care what some rich woman says, just because she lives in a big house, wears a crown and has a silly voice?”

We argued on and off about the monarchy for the rest of my mum’s life. And here I was, suggesting she had been right when she used to tell me the Queen was “special, wonderful, the best.”

Well, the piece prompted a response which delivered some good news amid the gloom. I was sitting at my desk the next day, and into my inbox popped the following email, from a stranger called John Watson, who had been prompted to write by his mother, Marjorie, who had read the article.

“Alastair. Hope you don’t mind me contacting you. I originally grew up in Kilmarnock (and am still an avid supporter of the football team, through thick and thin). My mother grew up on a farm on Fenwick Moor between Kilmarnock and Glasgow and it turns out that my gran, Isabella Young, was friendly with your mother.

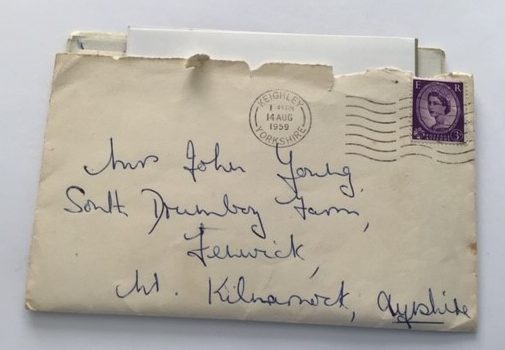

“My gran died a few years back, but recently my mother has been going through her things to help with mapping out the family history and came across some letters from your mum to my gran, written just after the birth of you and your sister. I’ve attached photos of the first pages below, and hopefully they might provide a welcome distraction in these dark times.”

They did indeed. We write so few letters in ink these days, but I find it hard to imagine a long-lost text or email could ever arouse as much emotion as a handwritten letter can.

There was something almost overwhelming about seeing, in her own hand, what my mother had written to a friend in the week I was born.

She was, like many of her generation, an enthusiastic letter writer. It was so nice to be reminded of her handwriting, which never changed even when she was old, and of the chatty writing style which reminded me of my time at university when she would write regularly to give me news of aunts and uncles, cousins, nieces and nephews, births, marriages, illness and deaths. And the weather, always the weather.

The letters Mr Watson sent were written in the place I spent the first three years of my life, Oakworth, Keighley, Yorkshire, where my Tiree-born dad, Donald, had a veterinary practice.

In one dated June,1957, mum seems happy enough with my arrival a week earlier, “sturdy wee chap” that I was, though I have always known, that had I been born a girl, there would have been no third son in the family, no me. Though she said she would not change me for anything, she did say: “Keep your fingers crossed for ‘Elizabeth’ next time.”

Elizabeth, my sister Liz, duly arrived two years later. Now, she and I are the last surviving members of the family, our two older brothers Donald and Graeme sadly dying at 62 (my age as I write, as if there was not enough to be anxious about right now!).

Liz will be delighted to know my arrival did not for a moment make mum believe her family was complete. In her letters, she did, however, say how much she had missed Donald and Graeme, who had been despatched to her older sister, my aunt Mattie Barr, at Pirntaton Farm near Galashiels, while she was in hospital giving birth to me. My brothers and I went there when Liz was born.

Auntie Mattie is still with us, incidentally, now 99, and as sharp of mind as ever but mum died six years ago this month, and I have been thinking about her a lot recently, not least because what would have been her first great-grandchild will shortly be born to my sister’s son, Graeme Naish, and his wife Leah, but also because of that broadcast by The Queen.

My mum was born, at home, Burnhouses Farm, Moscow, Ayrshire, on April 16, 1926. She was named Elizabeth Howie Caldwell. Five days later, to rather greater fanfare, another Elizabeth was born…yes, that one, the then-Princess Elizabeth who would go on to become the longest-serving monarch of all time.

So the Queen was a major figure in my mother’s life for the entirety of her 88 years on earth. She was a huge admirer. She would be totally unsurprised that the Queen recorded such a pitch-perfect broadcast at the height of this crisis. Even as I watched, I imagined her sitting there with us, smiling and nodding, and she would definitely have gone, “Ah, that’s wonderful,” when the Queen said the words “We’ll meet again”.

But she would still have been shocked that I tweeted just two words as the broadcast ended: “Queen. Quality.”

Later, Mr Watson’s mother Marjorie sent me the full letters written at the time, and two others, including when she was pregnant with me – “hoping for a girl!” – and one written at Christmas 1975.

That year, mum had decided not to send Christmas cards but then, when she started to receive them by the dozen, she wrote to everyone who sent one.

She writes of Donald in the 1st Battalion Scots Guards Pipe Band in Germany, soon leaving for Northern Ireland (not long after that, he would be invalided out after being diagnosed with schizophrenia) how Graeme was at university, I was hoping to go soon, and Liz was doing O-Levels in June. “How they quickly grow up.” Classic Mum.

We were living in Leicester at the time, and she confirmed something I always sensed. “Donald (my dad) is fine. But he doesn’t like the Midlands and would love to get back to Yorkshire or Scotland.” I felt exactly the same.

Mrs Watson told me her mother was Bella Nisbet from New Intax farm near Galston. Born 1925, died 2009.

“Mum always talked about Girlie [my mum’s nickname]and Nancy Caldwell [her oldest sister]. I’m sure they went to Grougar School together and were lifelong friends. Mum had boxes of letters, cards, etc and I have thought to send you these before but just didn’t get round to it. Yesterday, after reading your tribute to the Queen and the links to your mum, I looked them out again.

“My mum was a devotee of the Queen, too, and wouldn’t miss her on Christmas Day. She always followed your career with interest even if she didn’t agree with your politics!

“She would also have enjoyed your article. It is an unbelievably difficult time we are facing but reading the letters again made me think about how our parents grafted after the war to make a better life and how resilient people are. Your mum was a busy lady. Not much ‘me’ time for her.

“Anyway, here’s photos of four letters I found. If you send me an address I will post them to you as they would be nice for you to have.” They would indeed. Cherished even.

Mum didn’t just share the Queen’s name. They had similar hairstyles, warm smiles, and similar handwriting. You can see all three on the photos, of the Order of Service for her funeral on May 15, 2014.

After she died, we discovered she had left us a little poem, put away for us to find, with a note at the top “To go on the back page of the hymn sheet xx”. It reads:

Goodbye, my family,

my life is past,

I loved you all to the very last.

Weep not for me, but

courage take,

Love each other, for my sake,

For those you love

don’t go away,

They walk beside you

every day.

Thank you, Mrs Watson, and thanks, too, to your son, for thinking to send me the letters, and bringing so many fond memories during what, as you rightly say, are dark times for so many people, but times, also, to remind ourselves what and who are the things and people that really matter to us.

And mum would be happy to see this in The Sunday Post today, the paper which was mailed down each week and read cover to cover by both her and my dad, the Doc his favourite, Frances Gay hers. I was more into the sport and Oor Wullie but it helped inspire an interest in writing and newspapers, so here we are, full circle.

She would like that.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe