By the summer of 1892 the net was closing in on Sherlock Holmes.

The world’s most celebrated fictional detective had made his debut five years earlier. Public interest had grown – not least in the real-life model that had inspired Arthur Conan Doyle’s creation.

Doyle let the cat out of the bag in an interview with Harry How, a journalist on the Strand magazine.

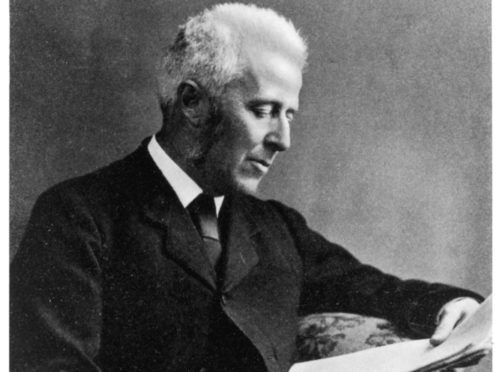

You could say it was a ding-dong moment: Doyle had based Holmes on acclaimed surgeon Joseph Bell, his former teacher at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. His observational skills, lightning diagnosis and scientific deduction readily transferred to Holmes.

He wrote to Bell warning him: “I am afraid that my little sketches have had the effect of setting a newspaper man on your trail with as great persistence as even Holmes showed to his criminals.”

Bell coped well with the press interest and remained on good terms with his former student, offering Doyle snippets as potential plot lines.

But what of the real Bell? Less well known is his enormous contribution to the development of modern nursing.

Bell paints a grim picture of nurses at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary in the 1850s: “Poor old useless drudges, half charwomen, half field workers, rarely keeping their places for any length of time, absolutely ignorant, almost invariably drunken, sometimes deaf.”

Surgery wasn’t much better. Robert Liston killed three during just one operation; the patient and one of his assistants whose fingers were accidentally amputated (both contracted hospital gangrene) and a spectator who dropped dead from fright when Liston’s knife cut through his coat tails.

Bell reckoned the introduction of trained nurses in theatres and wards at least doubled numbers of patients surviving treatment in hospital.

A revolution in surgery in the 1860s through anaesthetics and antiseptics coincided with a revolution in nursing spearheaded by Florence Nightingale.

She and Bell got on well. Nightingale sent up St Thomas’s nurses for head roles at Edinburgh Royal Infirmary. Bell was the first surgeon to offer lectures to nurses and he invited them on his Sunday ward rounds. Within a generation the infirmary had been transformed with sufficient qualified nurses and well-run theatres. In 1880 Nightingale offered thanks for “all he (Bell) has done so wisely and so well for the causes of trained nursing”.

The next challenge was nursing the sick poor in their own homes. Queen Victoria’s jubilee in 1887 provided the opportunity to set up an institute for training district nurses. The impetus came from William Rathbone in Liverpool and from Nightingale.

In Scotland the banner was taken up by three remarkable women committed to social reform.Christian Guthrie Wright, Louisa Stevenson and Princess Louise, Queen Victoria’s rebellious fourth daughter, had already established the Edinburgh School of Cookery – teaching nutrition and cookery.

Bell was involved from the outset as vice-president setting up the institute’s Scottish branch. Under his influence Queen’s Nurses in Scotland could only undertake midwifery, public health and district courses after three years’ hospital training. This was not required in England for large numbers of village nurse midwives.

For Bell they were the Queen Bees – supremely qualified. They had to be for the challenging work of district nurses in cities and in the remotest islands.

And they flourished – by 1900 there were 200 of them in post and by 1940 more than 1,000, paid in the pre-NHS era by nursing associations mainly funded by charity appeals.

Like Holmes, Bell had interests in chemistry, handwriting and accents. With his friend Henry Littlejohn, he offered forensic medical advice in murder cases.

Bell was also a devout churchgoer and family man – his hair turned white after the death of his wife Edith in 1874.

He was one of the first in Edinburgh to have a telephone and a motor car. He also served as a physician to nurses working at the Institute’s training home in Castle Terrace, Edinburgh, and its convalescent home.

On his death in 1911, fellow doctor Charles Douglas recalled: “Joe Bell was so many sided. The children, the women patients, the nurses all loved him for his kindness, his quick and ready sympathy, no one of them more so than she who knew him so well, his right hand through his long service, his beloved staff nurse, Jeanie Dickson on whose judgment he relied far more than on that of most of his residents.”

Queen’s Nurses are now back in Scotland – highly-trained leaders at the sharp end, providing care and leading change across the country.

In the book he wrote for nurses and dedicated to Nightingale, Bell urged: “Cultivate absolutely accuracy in observation and truthfulness in report.”

Holmes would have approved.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe