It occurred to me the other day that I don’t remember what my best friend’s perfume smells like.

I still see her fairly often; we’ve been lucky in that we live in the same village and our children play together. But I used to be able to tell what sort of day she was having by whether or not she’d put her perfume on. Now we sit at opposite ends of the playpark bench, make a point of our distance in the street. The space we leave is automatic, a forcefield stopping us getting too close. The thought of leaning in to laugh together or hug feels transgressive.

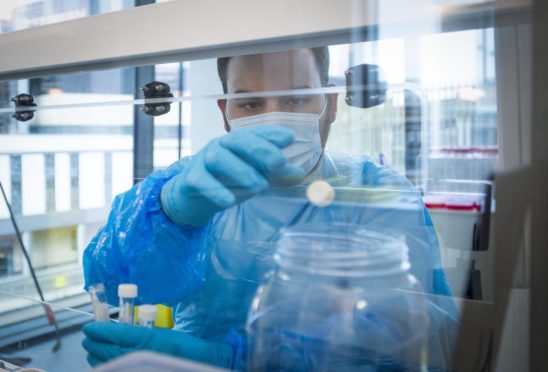

I would like to hug her. I would have liked to have dropped everything and let myself in through her garden gate, on that evening back in May when she texted me that she was hiding, zipped inside her wee plastic greenhouse, so that she could cry about her day at work without her little girl seeing. She’d held yet another person’s hand as they died without anyone they loved around them, and it had finally got too much for her.

That was May. I don’t know how she’s still going. In the before times, I would have taken her to the local after our kids were in bed, put an arm round her, bought her one of the fancy gins that poor Fraser the barman had to cut apple slices for. He would have sighed, but as long as it wasn’t too busy he would have brought them over to the table for us, with a wink. I hear he’s got work as a labourer. I hear the pub might not be able to reopen after all this.

My world got very, very much smaller a year ago, but hers stayed more or less the same. Mine stops at the woods just outside where we live, or the two centimetre-thick silver edge of my laptop screen.

She still makes the journey back and forth to the hospital, has colleagues and patients and patients and patients. The skin on my knuckles is as red and chapped as it was when I first had a newborn, in that paranoid haze of handwashing; but some days the PPE marks on her face are still there after a few hours’ sleep.

Do you remember how, a year ago, we looked on in horror as Milan, Padua and Venice locked themselves down? The viral videos of cheerful Italians serenading each other from their balconies as their lives froze panicked us.

In disaster movies, or maybe even in the zombie movies, it’s always the foreign news reports that alert the hero that something is wrong; as a society and as a country we certainly hadn’t taken the reports of a new virus in China seriously. Now, it seems, the world is watching us in horror with my cousin in Australia, where they locked down straight away, sending me messages of concern.

At first, the hugeness of the news seemed to make sense. We were suddenly living in end times and as every few seconds the news changed, pinging on our phones, we were scared to miss an update. That sort of drama is unsustainable. Remember when we passed 100,000 deaths in January, and seemed to be angry that we were too numb to be angrier?

My phone’s photo memory function flashes up, reminds me that exactly a year ago I was doing something I did regularly back then: sitting with other mothers while my children hurled themselves around four storeys of primary-coloured foam and rubber. Sometimes I think of all those empty soft plays, across the country. Perhaps there are new species of life forming in there, unseen by human eyes.

How could you ever make a soft play Covid-safe? A hazmat-suited worker going down the tunnel slide after each snotty toddler to disinfect it? This year, while the swing parks were closed, my kids got freckled and learned how to climb trees. The older one used to say wistfully that he would have his birthday party in a soft play when the virus was gone, but he hasn’t mentioned it in a while.

Try and tell those women crammed together at that fifth birthday party that in two months’ time they’d be fixed to their doorsteps clapping to mark each week off. Remember the Thursday clap? I did it with a growing sense of disloyalty because I knew how increasingly insulting my friend found it, as the body-count mounted, as the Thursdays went on, as Matt Hancock announced that NHS frontline workers would be getting a badge and a pay freeze. But still I opened my door at 8pm and I clapped, because I liked to wave and nod at the older couple across the road and the woman next door; it was the only time I saw them and I needed that certainty.

Remember when we put up rainbows in our windows, all of us, not just the kids? The slow fading of the felt pen colours – another way to track the passage of time. Our rainbow turned up under the sofa a few months ago, the sticky tape covered in dust. All those things felt important at the time, part of the war effort, the blitz spirit.

Other than my partner, I’ve had physical contact with three other adults this year: one illicit hug from my partner’s mum, who has been self-isolating for a full year now, released for a happy day in the garden in June and overcome at seeing us. In September, sitting in a beer garden by a loch on my 40th birthday, a 50-something biker woman from somewhere in the North of England put a conversational hand on my shoulder. When I asked her to give me space she yelled “Oh, don’t be a ninny. It’s all just lies you know. Look it up on YouTube. QAnon.”

Then there was the pal who picked me up from hospital after my toddler had a febrile seizure, who could see I was shaken from behind my mask and reached out to squeeze my arm. That one felt like an electric shock.

These days my best friend finds it difficult to use words to describe her working day; I think because there seems to be no end in sight. Once she mentioned feeling overwhelmed by the idea of a future of waves coming towards her, then one of our children started wailing about something and the moment went. Words weren’t appropriate then, and they were all I had to offer. I want to be able to give her a hug.

Kirstin Innes’ acclaimed novel Scabby Queen is out in paperback in April.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Bartosz Madejski

© Bartosz Madejski