When she set up the Everyday Sexism Project, Laura Bates admits she was naive. Until, that is, the rape and death threats started dropping into her inbox.

After detailing her own day-to-day experience of harassment and misogyny, Bates, then just 25, thought the online forum might provide a haven for women – 50, maybe 60 or so, she thought – to share their own stories of, well, everyday sexism. Some men online were unhappy and told her so in a stream of sinister threats and warnings.

“I’m definitely more jaded and cynical now than I was when I started,” she said. “I had this naive idea that everybody would embrace what I was doing because all I was doing was providing a platform for stories. You know, someone of any gender could share their story, so how could anyone have any problem with that?

“Then, three weeks later, I was getting 200 rape and death threats a day. The scale and the depth of the backlash has shocked me and it’s made me a lot less naive and perhaps a little bit less optimistic.”

She installed high-level security in her home, and Bates takes some encouragement from the more than 200,000 testimonies she has now received from around the world which have made her “grimly determined” to chart what she believes is systemic sexism at the heart of our society.

Movements like #MeToo may have opened up the conversation but, as Bates points out, every day the news is filled with examples illuminating a widespread and entrenched problem.

In politics, to take just one example and a few recent weeks, Labour’s deputy leader Angela Rayner was compared to Sharon Stone in Basic Instinct, MP Neil Parish admitted watching pornography in the House of Commons chamber, and in the US, a leaked draft Supreme Court opinion suggested the landmark Roe v Wade case securing women’s right to abortion could soon be overturned.

After so many years, so many stories, it can be easy to think nothing has changed. Bates said: “It’s a roller coaster between hope and despair. It feels almost every day brings some fresh blow. It does feel endless and there’s a real risk of desensitisation. There’s almost so many of these stories, how do you work out which bit to focus on?

“But there are a number of concrete examples of positive change that have come about directly connected to the project and more widely over the last 10 years we’ve certainly seen a sea change in terms of the public conversation. We are talking about and acknowledging sexual harassment and sexism in the public sphere now in a way that even 10 years ago wasn’t the case.

“There’s been a shift in terms of awareness, certainly, and that’s really positive and very important but it’s also only the first step, it isn’t the solution.”

So, what is the solution? For too long, Bates argues, women have been burdened with making change happen by sharing their stories and raising awareness through what she described as “individual incidents” – each woman’s personal list of uncomfortable, upsetting and violent moments that are sadly so common.

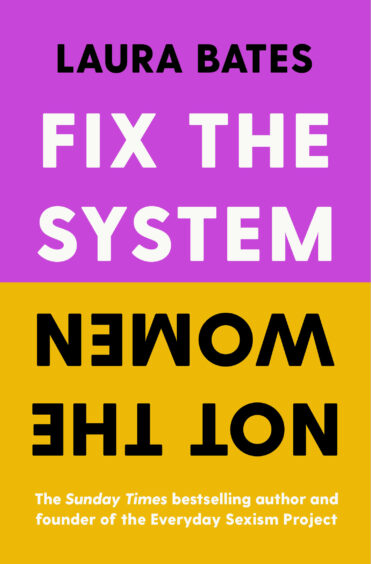

In her new book, she argues it’s time to move past conversation and towards action, connecting the dots between these personal stories and the systemic misogyny behind them. Combining first-hand accounts with research and detailed evidence, Fix The System, Not The Women, published last week, explores the societal systems that are “suffused with institutional inequality”, and makes a strong case for embracing root-and-branch reform across education, policing, criminal justice, politics and the media. “For 10 years, I’ve been focusing on individual incidents, trying to get people to listen to women’s voices and stories, trying to get people to believe them, to recognise that this is happening,” said Bates, who has now written six books, including The Sunday Times bestseller Girl Up.

“This book, I suppose, marks a new phase of saying, OK but now we need institutional response to those individual voices if we want to see really significant lasting, sustainable change.”

Bates argues in the book “nothing will truly change until we acknowledge that the problem is with the system, not the women” and, while solutions already exist, political will is also required to make them happen.

She continued: “Really brave and radical solutions have been recommended for decades by frontline women’s organisations with the relevant expertise to make those suggestions. And yet when a crisis happens, and when the spotlight swings on to issues like women’s safety, for example, the government tends to shrug its shoulders and throw out half-baked ideas about CCTV cameras or the police suggest flagging down buses.

“If we look at the reports and the recommendations of organisations like Rape Crisis and Women’s Aid over the last decade, the suggestions are there. The scalable, brave, radical changes we need to see actually have been put down on paper.

“What’s more, there are pieces of proposed legislation, for example, which would make an enormous difference to the vast and interconnected and challenging picture. The new legislation in Scotland suggested by Baroness Kennedy and her working group, or the ratification of the Istanbul Convention, is something that government could do overnight.

“Just because it’s a big problem, and just because it’s complicated, doesn’t mean that there aren’t actionable solutions there. It’s very frustrating when people paint that as the reason that change isn’t happening. The reason is that there isn’t political will to make the change.”

The statistics outlined in Fix The System, Not The Women make it clear how drastically change is required. One in four women in the UK, for example, will experience domestic abuse, while 85,000 a year will experience rape or attempted rape. Almost a third of teenage girls, too, say they have been sexually assaulted at school, something which was further highlighted in The Sunday Post’s recent investigation into harassment in schools.

Often, Bates says, women are expected to take precautions to keep themselves safe – whether interlinking keys between their fingers on a walk home or keeping a hand over their glass in a bar – and so tackling this normalisation is just one of the steps required to end violence against women.

She said: “Normalisation is key to why people baulk at the idea of considering misogyny a hate crime, and key to why we don’t label incel terrorism as terrorism, even though that’s what it is. These things are normal because violence against women is so utterly, deeply normalised in our society.

“It’s so difficult to force people to tackle the problem when you first have to force them to open their eyes and see something that they’ve been trained their whole lives not to notice.”

“My hope for this book is that men will press it into other men’s hands,” said Bates. “We hear a lot of men talking about wanting to be part of the solution, and informing themselves about the problem is probably the first step.

“That’s also why, for me, it was really important to campaign around education and what’s on the curriculum because we can’t force every man to sit down and listen, but we can get every child of any gender to be given proper age-appropriate supportive education around these issues.”

She added: “It is a brave thing, I think, for men to disrupt that normalisation and those societal stereotypes about how men speak to each other, particularly in male-dominated spaces, locker rooms, on sports pitches and in private WhatsApp groups.

“I do think it’s something all men should be doing but I also think it’s hard and it’s OK to acknowledge and recognise that it’s hard. But, you know, my response is, if this is hard to talk about for you, imagine how it feels for us to live it.”

Fix The System, Not The Women, Simon & Schuster, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe