It has taken three years, heard the testimony of thousands of children and adults with experience of Scotland’s care system, and spoken to scores of experts in an attempt to map a new way ahead.

And, for Fiona Duncan, who has led the Independent Care Review, every minute of it has been a labour of love.

Days before publication of a review she hopes will mark a step-change in how Scotland cares for its most vulnerable children, she told The Sunday Post why the current system is failing so many young Scots.

“This thing that we call a care system is not delivering the best outcomes for every single baby, infant, child and young person,” she said.

“In its current state, it is not a system. It doesn’t operate as a single entity. It doesn’t serve anybody. There is far too much bureaucracy involved. Too many different rules.

“For children and young people, that can be incredibly confusing and the language used can feel very stigmatising.

“The time frames of parts of the system also don’t align with children’s lives, for example, long waiting times for appointments and hearings. All that gets in the way of childhood.”

Commissioned by Nicola Sturgeon, the Care Review is the result of a 36-month comprehensive investigation and research into all aspects of the care system – and its impact on those who go through it.

When the First Minister announced a “root-and-branch” independent review of Scotland’s care system in October 2016, she made a direct and emotional pledge to listen to and improve the lives of children and young people in care.

For Fiona, this meant the review had to be shaped by the powerful testimonies of children across Scotland who had experiences of the care system.

The Independent Care Review, inspired by the advocacy work of national charity Who Cares? Scotland, has spoken to 2,600 care-experienced children and young people, as well as 2,500 parents, carers and people working in the sector. It will be published on Wednesday in Edinburgh.

“This review had to look and feel different. It’s about making the system adapt to the person,” said Fiona, who also ensured 50% of her team had personal experience of Scotland’s care system.

“We learned things about what life should be like for care-experienced children and young people by listening to them. Most of the children and young people I’ve met want the same chances as everyone else.

“They want an ordinary life. They don’t want to feel different. They just want to be loved, have a normal childhood and go on to be happy, healthy adults able to give and receive love.

“This review has an opportunity to produce an approach for Scotland that could be enabling and loving, where children can thrive and grow up to fulfil their potential.”

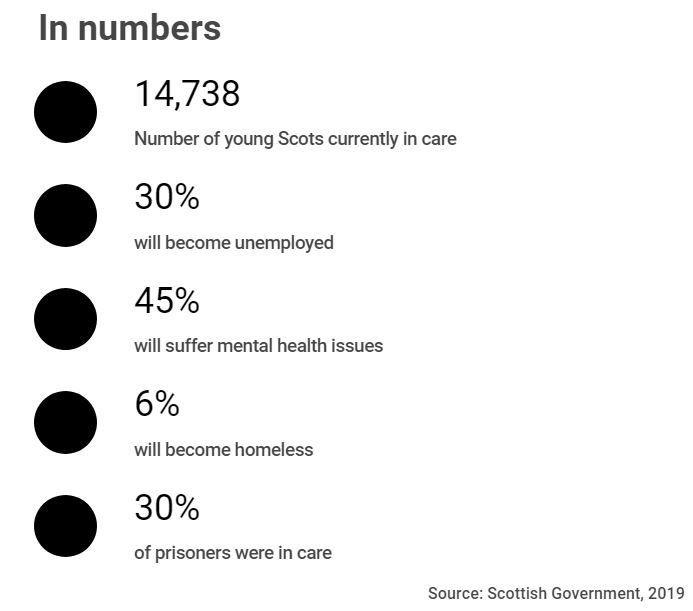

But statistics suggest just 4% of care-experienced young people will go on to higher education, 30% will end up homeless and nearly half are diagnosed with mental health issues.

“We do not think these young people have failed, we think the system has failed them,” emphasised Fiona, who is also CEO of the Corra Foundation, which offers grants to those who face adversity, and has worked in the voluntary sector for over 20 years.

One of the key things Fiona found while speaking to people about their experiences of care was the crippling uncertainty felt my many about their, and their family’s, future.

“The key thing that struck me is the lack of control, the lack of engagement and the lack of knowledge,” she said.

“I think it’s also important to note that I have heard some beautiful, uplifting stories, particularly about people in the workforce who have gone above and beyond for the children and young people in their care.

“But generally, the ‘system’ is not operating effectively and there are things that are truly awful and need to stop, like separating brother and sisters.”

There are currently no statistics on siblings in care, but latest research suggest around 70% are separated from their siblings on entering the care system.

“It is shocking that, when a child or children are removed from their families, they are then separated from their siblings. It’s completely unacceptable,” Fiona added.

“Whenever it’s safe to do so, brothers and sisters should be kept together.”

Fiona hopes The Independent Care Review will bring about lasting change but implementing its findings will require a collaborative and universal approach.

“What happens next is really important. This can’t be a review that sits on a shelf somewhere and the government considers whether it is implemented or not.

“Action has to happen but the big challenge is that the Scottish Government can’t do this alone.

“There is a local, national, public, voluntary and a private aspect to this. Local authorities, health and social care partnerships, charities, and national organisations like The Children’s Hearing System and the Scottish Children Reporter, they all have to come together and build a plan to implement this review.

“This is a moment in time where we have people ready, willing and able to do this. We have to deliver on it.

“But it will require a different approach, one that has the voice of care-experienced children and young people right at the heart of it.”

The charity bringing lost brothers and sisters back together

Witnessing the pain and trauma felt by brothers and sisters torn apart by the care system inspired foster carer Karen Morrison to reunite and foster the bonds between siblings in care through her charity STAR: Siblings Reunited.

Based on a farm in Cupar, Fife, STAR offers a safe space for estranged siblings to reconnect and make positive family memories, whether through planting vegetables, cooking meals outdoors, tending to animals or simply watching a film together.

“It’s heartbreaking. In many cases, these siblings are the only family each other has,” said Karen, 46.

“Then suddenly they’re split up and don’t know if their brothers or sisters are OK or even where they are. It’s clear to see the stress and anxiety caused by that separation. They carry the weight of the world on their shoulders.”

Karen believes more must be done to protect the rights of siblings placed in care and that enabling consistent contact with siblings should be prioritised.

“I’d like to see more rights for looked-after siblings in care because, at the moment, they have none.

“When children get separated, whether in foster care, kinship care or adoption, each child has separate hearings and LAC (Looked-After Child) reviews.

“Important decisions about that child’s future can be made at these hearings but their brothers and sisters are not party to that, so will be completely unaware of any decisions made.

“If a court has ordered parent contact once a week, it’s going to happen, but if a panel suggests monthly contact with brothers and sisters, there’s no legal obligation for this to take place, and this can lead to contact between siblings being fraught and inconsistent.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Steve Brown / DCT Media

© Steve Brown / DCT Media © Steve Brown / DCT Media

© Steve Brown / DCT Media