When asked by other golfers what his handicap was, Sammy Davis Jnr would say that he thought being a one-eyed black Jew was enough.

From the moment he set foot on stage, aged four, and began copying the dance moves of the Vaudeville performers around him, Sammy believed the adoration of an audience could overcome his own self doubt and insecurity. It was a feeling that never left him.

A performer of spectacular gifts, he was often described as the ultimate song and dance man. Recording artist, movie star, stage and cabaret performer, he did it all. Yet he succeeded in destroying himself with alcohol, cigarettes and drug abuse, dying from throat cancer 30 years ago this week at the age of 64.

For the award-winning Hamilton star Giles Terera, cast as Sammy in the forthcoming stage musical of the same name, challenges don’t come any tougher.

The child Sammy’s world was all about performing and being acclaimed by strangers for his prodigious talents, rather than education and domestic routine. Aged five he went on the road with the Will Mastin Trio, which included his performer father Sammy Davis Snr, playing hotels and nightclubs.

His father attempted to hire private tutors to appease truant officers. Sammy quickly became the act’s main attraction. By 17 he was a Vaudeville veteran. He was drafted into the US Army at 18 where initially his talents went unnoticed.

Fellow recruits saw only a short, odd-looking black guy with a flattened nose and an inability to read well. He said of his military experience: “Overnight the world looked different. I must have had a knock-down, drag-out fight every two days.”

He had to work hard at neutralising the routine racism by playing the likeable clown who made everyone laugh. He said: “My talent was the weapon, the power, the way for me to fight.”

After the war, hardened by his experience, Sammy was ready for mainstream stardom.

In 1951 the Will Mastin Trio were booked to support the singer Janis Paige at Ciro’s nightclub on Sunset Boulevard, LA, but the high-profile audience were so enthusiastic about the little rocket-fuelled black guy that their 20-minute slot soon became an hour – and Sammy became the talk of the town.

The turning point for Sammy was the 1956 Broadway show Mr Wonderful, created specifically to showcase his versatility, and serving as a springboard for the Las Vegas nightclub act that allowed him to show off his musicality, his dance moves and his gift for mimicry.

Other top entertainers of the day flocked to see him perform which is how his friendship with Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Joey Bishop and actor Peter Lawford – who became known as The Rat Pack – came about.

In 1964 he won further plaudits for the musical Golden Boy, based on a play by Clifford Odets, in which he played a young guy from Harlem who turns to prizefighting to escape the constraints of the ghetto, and falls in love with a beautiful white girl.

Sammy said at the time: “Golden Boy is me. I know exactly what it means to be involved in a love story of that kind, to feel yourself stared at when you walk down the street, to feel humiliated, knowing that you’re going to get very hurt.”

At the time he was married to Swedish-born actress Mai Britt which fuelled racist hate mail directed at the couple.

It was also said that Davis’s inter-racial marriage – still regarded as provocative in the US in the 1960s – was the reason he was blocked from appearing at President Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961, even though he’d been an outspoken supporter of Kennedy’s campaign, and possibly why Sammy went on to support Kennedy’s Republican rival Richard Nixon in his 1972 campaign to become president.

In the later stages of the Vietnam war, at Nixon’s request, Sammy travelled to Vietnam to entertain the US troops and to observe military drug abuse programmes.

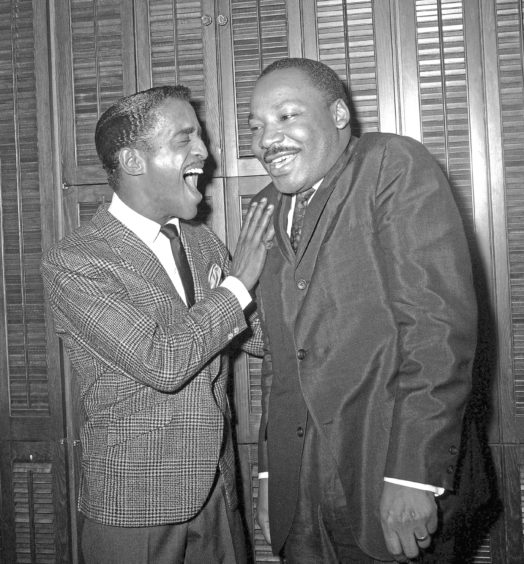

Just as the American public was sometimes confused about his political allegiances, so it was also baffled at times by his stand on civil rights.

On the one hand he spoke out against racism and prejudice, on the other he seemed to be happy to be denigrated in public for his appearance and his “difference” by the likes of Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and co.

He often appeared to become the fall guy for The Rat Pack as if that was the inevitable price of fame for a black entertainer in a white world.

There seems little doubt that his celebrity, and all the privileges that went with it, distorted his world view though he would always insist that the fight for civil rights was at the top of his agenda.

In an interview with the journalist Oriana Fallaci in 1968, he said: “I’ve never gone by rules set by other people. I’ve always felt that they don’t count for anything, rules, if your own conscience doesn’t want to accept them. So don’t tell me I can’t have that Rolls Royce because it’s against the rules, don’t tell me I can’t marry a white woman because it’s against the rules. It’s never been done? Then I’ll do it.”

He believed his success as a entertainer of international repute struck a blow for civil rights.

“I never enter a club that won’t admit other negroes,” he told Fallaci. “I never enter a restaurant that won’t admit other negroes. I never work in a theatre or a movie that doesn’t give work to other negroes, because I can’t forget that if I’m admitted, it’s because others entered before me.

“They opened those doors, little by little, so that I can open them a little wider. The fact that many doors are open to Sammy Davis Jnr means that the same doors are open to others.”

As well as the stage musical Sammy, which will be produced later this year, a film of Sammy’s life is in the pipeline, with singer Lionel Richie as one of the producers. His memory is also kept alive by the comic actor Billy Crystal’s brilliant impersonation of Davis, as well as by Don Cheadle’s portrayal of him in the 1998 TV movie The Rat Pack.

There is also a ghosted autobiography Yes I Can, published in 1965 at the height of his success, and the more recent biographies – In Black And White (2003) by Will Haygood and Sammy Davis Jnr: A Personal Journey With My Father (2014) by Tracey Davis, his daughter with Mai Britt.

Sammy’s self-destructive streak finally caught up with him in 1990 but not before the great and the good of America’s entertainment world – Ella Fitzgerald, Diahann Carroll, Clint Eastwood, Eddie Murphy, Michael Jackson and others – had paid tribute to the great entertainer in the TV special Sammy Davis Jnr 60th Anniversary Celebration.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Warner Bros/Kobal/Shutterstock

© Warner Bros/Kobal/Shutterstock © Dave Pickoff/AP/Shutterstock

© Dave Pickoff/AP/Shutterstock