Her athletic career may have instilled in her true grit and endurance but, even for professional triathlete turned screenwriter, Lesley Paterson, her new movie was a marathon.

It took 16 years for her to drive All Quiet On The Western Front on to the screen but now, as the First World War drama is hailed by critics and tipped for some of the industry’s biggest awards, Paterson credits the same determination that made her the only girl to play rugby growing up in Scotland.

The German-language Netflix film was last week nominated for 14 Baftas – including best film, director, supporting actor and adapted screenplay – with critics expecting it to feature when the Oscar shortlists are announced on Tuesday.

She said: “We are so honoured and excited that our film was nominated in so many categories. After 16 years of pushback, this is such vindication that our instincts were in the right place. We feel so lucky to have partnered with director Edward Berger, producer Malte Grunert, and Netflix, to elevate and take this project to another level.

“It’s just unbelievable, so surreal. It’s all I’ve ever dreamed of and now it’s happening I’m trying to soak it in. It all seemed unimaginable however many months ago, and then all of a sudden there was traction.”

It was in 2006 when she and writing partner Ian Stokell acquired the option to Erich Maria Remarque’s 1929 novel from its copyright owner and, renewing the option every year, they fought to attract the interest of studio executives in a retelling of the story of the First World War from the German perspective and in their language.

The twisting, torturous progress to the screen was gruelling mentally and, in 2016, physically when Paterson had to overcome a broken shoulder after falling off her bike in a triathlon race to finish in first place, winning the cash prize that allowed her to make the option payment and keep the dream alive.

“It’s really trying to pivot on a bad situation – how can I turn it around and make it a positive?” she added. “Dealing with adversity teaches you so much and makes you much more resilient for the future. Sport is an exercise in resiliency and so is film. Every step of the way I’ve utilised those skills and transferred them across into this new business.”

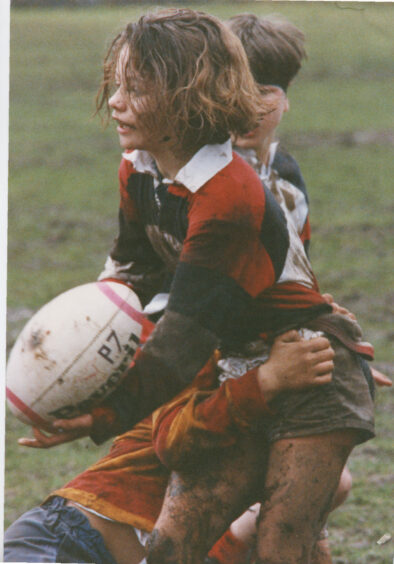

Paterson, 42, may be a triathlon champion, having competed since the age of 14, but rugby not athletics was her first passion. She said: “I played in an all-boys team, 250 boys and me at Stirling Country Rugby Club, that tells you all you need to know about my personality!

“I think I was the only girl in Scotland playing rugby at the time because this was the 1980s. On a Saturday morning I’d play rugby with the boys and in the afternoon I’d do ballet dancing. I used to show up with all these prim and proper little girls and I’d have muddy knees and my ballet pumps on. I’ve always loved the dichotomy.”

Paterson focused on theatre at university and, when she moved to the US when husband Simon Marshall, a psychology professor, got a job in San Diego, she continued her studies in California. It came at a time where she was disillusioned with sport and competing, and wanted to put more effort into writing.

“It had become emotionless for me and I’d lost the passion and the joy behind what I was doing. It was largely due to the system of how sport was put together in the UK.

“It was very science and data-driven and I’m a very emotional athlete. I have a big heart, and that isn’t really taken into consideration. I felt like the joy and passion was beaten out of me a bit.

“Going back to the arts, I rediscovered what makes me tick. I knew I had confidence and realised I had to find my own way to the top and not be manufactured by a system. I think that’s why I got success. Alongside being a professional athlete I was always writing, producing, having those creative juices bubbling away at the same time.”

She did eventually return to sport after realising she missed competing and rekindled her love of triathlon through off-road Xterra events.

Since moving to the States, her two passions have constantly overlapped, with training and discipline required across both.

“Throughout my sporting career, what I realised was that if you focus on the process, not the outcome, then the outcome comes,” she explained.

“The craft is truly what makes you brilliant, being the best you can be. We did that in screenwriting terms, taking classes, writing, re-writing. From that perspective it was the same as my sport, the way I trained, always learning new techniques and working with new people. The pursuit of excellence, and understanding that every knock back, every ‘failure’, is an opportunity to learn and grow.

“You stop absorbing the negativity and realise that success is like a cargo net rather than a ladder, there are so many different routes. Thinking outside the box is actually what’s going to get you there. Every step of the way in my athletic career I’ve had to do that, struggling with chronic Lyme disease and myriad pretty severe injuries.

“That all applies to film. You have to be so dynamic to get a project off the ground. It’s incredible how you have to think about all these pieces and how they can fit together.”

Now, as her film hurtles into the award season, Paterson admits the furore around the movie is hard to compute. “Sometimes when it’s actually happening you almost can’t be in the moment. We were at an event last week where every star you could imagine was there. I was sitting beside Kate Hudson, I spoke to James Cameron, Guillermo Del Toro… it was bananas!”

The film is already picking up awards, with Paterson and Stokell scooping the Best Adapted Screenplay gong at the National Board Of Review’s Gala earlier this month. They were presented the prize by Sienna Miller with movie legend Steven Spielberg in the front row.

“How nervous was I!” she laughed. “I didn’t realise how big an event it was until I got there and then I had to speak in front of all of those people.

“I’m used to being in front of the camera, public speaking and coaching. You just can’t let it get in your head knowing who’s in the crowd.”

She loves living in California, where her morning runs are in glorious sunshine along the palm tree-lined shore, but says her home and heart will forever be in Scotland, with her family in Stirling and the Highlands.

“There’s something about the Scottish people – we’re genuine, down-to-earth, kind and generous,” she said. “When I come home, I take a deep breath. Maybe what’s made me successful out here in California is the fact I have that underdog fight, that Calvinistic approach to life, one of suffering, which I kind of love. I get a perverse kick out of it, so if something is really, really hard I’m going to do it.

“But at the same time, there’s a beauty in California, that American dream of anything being possible, that I don’t get in Scotland. There’s a pervasive kind of negativity sometimes in that Scottish culture. Over here, it really feels like the sky is the limit.

“I think people are attracted to work with both myself and my husband because we have the humility of being Scottish and English. But, at the same time, we have big dreams and we don’t care if we fail, we just keep going.”

Paterson hopes to be home fairly soon, with involvement in the setting up of the Scotland International Festival of Cinema in Peebles in March, and also plans to shoot a forthcoming project in the Highlands.

“I have lots of ideas set in Scotland and that’s really my dream – to come home and be able to shoot films so I can be with my family but doing what I love. We have one we’re going to shoot, hopefully near Glencoe, a psychological thriller set in the Highlands.

“We already have a great director, a wonderful script, we’re putting together finance and applying for funding with Creative Scotland and the BFI. So we’re really hopeful we can shoot that this year. That would just be amazing.”

Her plans come at a time when the film industry in Scotland is booming, with blockbusters like Batman and Indiana Jones being partly filmed here. “People will be attracted to film in Scotland for many reasons,” Paterson said. “The beautiful scenery and architecture, the depth of history, but also the work ethic, the crew-base and the artistry in talent. There’s so much of it that hasn’t seen the light of day and now we’re in a place where we can start to discover that talent.

“I grew up feeling like, if you’re from Scotland, it’s virtually impossible to get to where I’ve got to in Hollywood. And it isn’t, you’ve got to believe in yourself. You’ve got to keep creating and doing and getting the word out and you can make that happen.

“It is a weird business and as you get further up the chain you see the luck and the different variables that have to come together to make it work.”

It’s so compelling to see it from the other side

The anti-war epic All Quiet On The Western Front by Erich Maria Remarque, a German veteran of the First World War, was first published in 1928.

It tells the story of Paul Bäumer, a German soldier on the front, stripping out the heroism and adventures of other war stories and focusing on the physical and mental cost of the conflict.

Its themes of the scarring toll of war, the disposability of those on the frontlines and the weaponising of patriotism led to it being one of the books banned and burned in Nazi Germany.

The book was adapted as an Academy Award-winning film of the same name in 1930, directed by Lewis Milestone. It was adapted again in 1979 by Delbert Mann, as a television film starring Richard Thomas and Ernest Borgnine.

The latest version was released last year, directed by Edward Berger, with the screenplay by the German director alongside Ian Stokell and Lesley Paterson.

It has been nominated for 14 Baftas including best film, director, supporting actor and adapted screenplay, tying it with 2001’s Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon as the foreign-language film with most nominations in the awards’ history.

“It’s such a gorgeous novel that’s told from the other side,” Paterson said. “I feel like, nowadays, we’re so myopic with our thinking and only see it from our side. We’re never putting ourselves in other people’s shoes.

“Our research hung a lantern on the importance of understanding an enemy’s perspective and where they’re coming from so that things aren’t repeated. Seeing it from the other side was such a compelling and interesting thing for us.

“World War I is a wonderful sandbox for a film-maker or writer. It’s such an intense world, an alien-like world that’s unimaginable and heightened.

“Netflix were the quickest to jump on board and say we want to do this. Edward and [producer] Malte Grunert said this was their national novel, so we wanted to honour the piece by doing it in authentic German.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Lesley Paterson

© Lesley Paterson © Lesley Paterson

© Lesley Paterson © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM