THIS year – the 100th anniversary of the end of the First World War – is a good time to correct the belief that the Post Office was ever a place for the faint-hearted.

So many employees enlisted when war broke out – some 75,000 – that it formed its own 12,000-strong battalion, the Post Office Rifles.

Half would be either killed or wounded climbing out of trenches and fighting as foot soldiers on the Western Front at Ypres, the Somme and Passchendaele.

Their effort prompted one Divisional General to tell them: “I thought you were a lot of stamp-lickers, but you went over like a lot of bloody savages.”

No fewer than 145 of these men would receive gallantry medals, which is a lot of brave postmen.

Birmingham-born Alfred Knight worked as a clerk in the Post Office’s North Midland Engineering District and was 26 when he signed up for the second Post Office Rifles. He left for France in January 1917 and was made a sergeant after the Second Battle of Bullecourt, in which he brought in wounded men under heavy fire.

He was awarded the Victoria Cross for what he did in the Battle for Wurst Farm Ridge at Ypres on September 20 1917. The London Gazette described it as the “most conspicuous bravery and devotion to duty during the operation against the enemy positions”.

Pinned down by two German gunners, he twice left the trench to single-handedly run through the barrage of fire with his rifle with bayonet fixed, surprising and scattering the post of 12 men and capturing the machine-gun.

Years later, Knight remembered the pattern the German bullets made in the mud as he ran: “All my kit was shot away. Bullets rattled on my steel helmet – there were several dents and one hole in it I found later – and part of a book was shot away in my pocket. A photo case and a cigarette case probably saved my life from one bullet, which must have passed just under my armpit – quite close enough to be comfortable!”

Back home, women filled the void in the postal service.

Realising how important it was for soldiers’ morale, mail was sorted in a five-acre shed in Regent’s Park. According to the British Postal Museum & Archive (BPMA): “It was said to be the largest wooden structure in the world, employing over 2,500 mostly female staff by 1918. During the war, the London Home Depot handled a staggering two billion letters.”

As well as helping troops stay in touch with families, the Post Office handled Britain’s telegraph and telephone systems, banking and a Relief Fund for widows and orphans of employees, and distributed recruitment forms and ration books.

It also issued the Government’s new “Separation Allowances” to soldiers’ wives who’d been left with no income – on one condition that doubtless raised eyebrows both then and now. Women could only claim the allowance if they were faithful to their husbands.

The arrival of 35,000 women to do Post Office work “made many uncomfortable”, writes the BPMA. More “uncomfortable” must have been most of those women, who were promptly replaced by men after the war and would have to wait another decade before gaining the right the vote.

Temporary staff members or not, it was largely these women who drastically overhauled the Post Office to cope with the changes. The amount of mail increased dramatically: 700,000 items in October 1914 grew to 13 million by the end of the war. Services offered in peacetime were cut back – some rural towns saw only one or two deliveries a day after being used to 12!

The war also brought to an end a British institution. For 75 years, the Penny Post had held the price of sending a standard letter to exactly one penny. But the war so drained the Government of cash that in June 1918, the Treasury added a halfpenny to that price.

As one historian observed: “One of the great triumphs of peace had succumbed to the demands of war.”

Not only did the Post Office try to go about its business during the war, cities like London did so while being bombed. One air raid in July 1917 brought down part of the roof of the Central Telegraph Office and the telegraph system.

“Offices in Birmingham stepped in and the CTO was up and running in three days,” says the BPMA. “No one was hurt thanks to a national air-raid warning system developed by the Post Office Engineering department.”

That department also designed telephone and telegraph equipment for the trenches, with 11,000 engineers dodging shells to lay or repair the lines.

Some 19,000 mailbags a day crossed the Channel to France, where the Army Postal Service loaded them into lorries and carts. The touching carefulness of this operation belied the terrible reality that many would-be recipients were no longer alive to read them – 30,000 letters a day remained unopened.

Some were lucky though. Infantryman Reg Sims wrote home: “In exactly 12 months, I have received 167 letters besides paper and parcels, and have written 242 letters.”

The worry with the rapidly growing number of letters and telegrams was security. Since letters home could unwittingly provide the enemy with useful information, the War Office decided to censor all mail.

Grumbles about conditions or other signs of low morale could be exploited by the enemy, so were duly censored, as was any talk of awful battle experiences that might upset families – the Government’s way of keeping the public’s spirits up and maintaining support for the war.

Over 12 million letters were sent to the troops every week, and censors had to read every one. And they still managed to deliver them in two days.

Admittedly, censoring was far from a perfect art form. Former postie and Home Secretary Alan Johnson MP told the BBC that “forbidden subjects were either ripped out or simply scribbled out. In some cases censored words remained readable.”

Some letters that did get through proved poignant.

“Dear father,” began one, now held in the Imperial War Museums. “They have been teaching us bayonet fighting today and I can tell you it makes your arms ache. I think with this hard training they will either make a man of me or kill me…From your loving son, Ted.”

Edward Poole was killed in action two months later, age 18.

Another letter reads: “My own beloved wife, I do not know how to start this letter. We are going over the top this afternoon and only God in Heaven knows who will come out of it alive. If I am called my regret is that I leave you and my bairns. Oh! How I love you all and as I sit here waiting I wonder what you are doing at home. I must not do that. It is hard enough sitting waiting. Goodbye, you best of women and best of wives, my beloved sweetheart. Eternal love from yours for evermore, Jim xxxxxxxx”.

Company Sergeant Major James Milne was one of the lucky ones. He survived and was later back with his family.

While words of affection stood a chance of getting through, it was quickly realised what kind of messages to watch for.

To crack those written in foreign languages the War Office hired thousands of bilingual women. Helped by the Post Office, they intercepted compromising mail that led to the capture of enemy agents.

The most famous German spy was Carl Hans Lody, a lieutenant in the German Naval Reserve who travelled on a US passport under the name of Charles Inglis and spoke fluent English.

“He was detected in his very first message home,” according to MI5. It had been sent to an Adolf Buchard in Stockholm, to an address MI5 knew was a cover for German intelligence.

When war began, Lody travelled to Edinburgh to spy on the Firth of Forth, where Royal Navy ships lay at anchor.

“Lody had little training for espionage,” writes MI5. “His only means of communication was by telegrams and letters which he sent using a simple code. Some were allowed to go through because they contained misleading information.

“He sent letters about a supposed landing of ‘large numbers of Russian troops’ in Scotland. There was no truth in the story, but it caused great concern to the German military.”

It was when he went to Dublin and wrote in German with no coding about ships he’d seen there that censors intercepted the letter and MI5 decided to order his arrest. The police tracked him to County Kerry, and discovered his true identity when they found a tailor’s ticket in his jacket bearing his real name and an address in Berlin!

Amateurish or not, Lody had guts.

Admitting he was a spy and facing a highly publicised trial and death sentence, he refused to name his recruiters, saying: “That name I cannot say as I have given my word of honour.”

As MI5 details: “His patriotism and honour attracted widespread admiration in both Britain and Germany.

“Taken to the Tower of London to be executed on 6 November 1914, he was reported to have said to the officer who escorted him: ‘I suppose you will not care to shake hands with a German spy.’ ‘No,’ the officer replied, ‘but I will shake hands with a brave man.’”

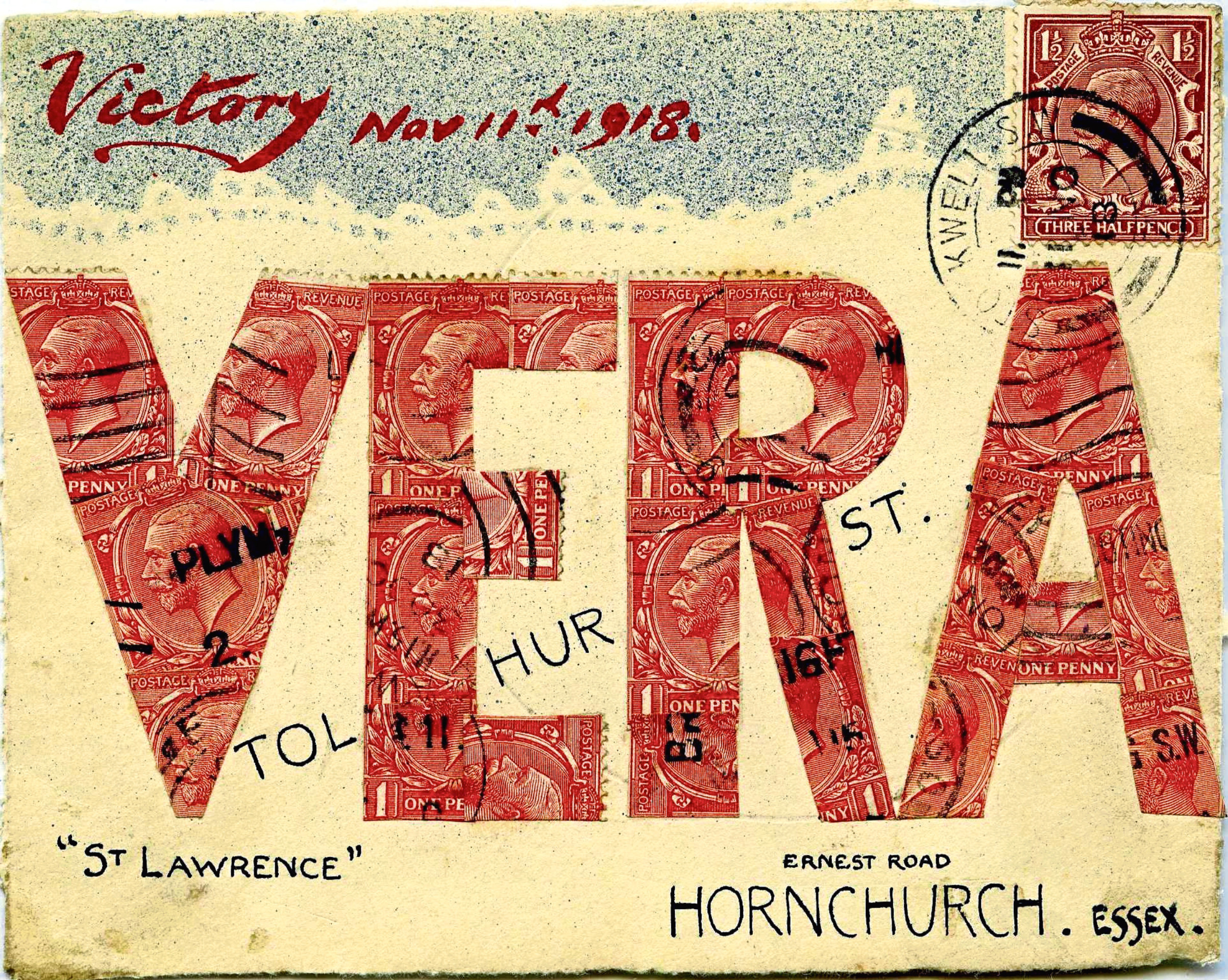

The joy felt by the public when Armistice Day finally arrived on November 11 1918 can only be imagined. But one soldier knew just how to express it in a postcard he sent to someone, presumably a girlfriend or wife, called Vera Tolhurst.

Simply marked “Victory, Nov 11th 1918”, not only did his postcard say farewell to the age-old Penny Post in the dramatic way he chopped up penny stamps to write her name with, but it seemed to shout out his feelings not just towards Vera but about the freedom and safety that had finally returned.

“Voices from the Deep” at the Postal Museum in London will run until June 30 2019.

Sunken, forgotten, then saved from the ocean, the exhibition showcases 700 letters trapped at the bottom of the Atlantic for 70 years, preserved in an airlock that formed as the SS Gairsoppa sank in 1941.

Entry is included in the price of entry to The Postal Museum. Visit www.postalmuseum.org

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe