Liam McIlvanney has been practising his Tam o’ Shanter for a long time. On Tuesday he’ll get to do it before anyone else.

“Slightly embarrassingly, I’ve been able to recite it in its entirety since I was six years old,” said the author, ahead of his appearance at a Burns Supper at the Toitu Settlers’ Museum in his adopted home country of New Zealand, where Burns Night arrives a full day before it does in Alloway.

“My old man hothoused me into learning the poem. It’s quite useful to clear pubs at last orders. You start that and people run for the hills.”

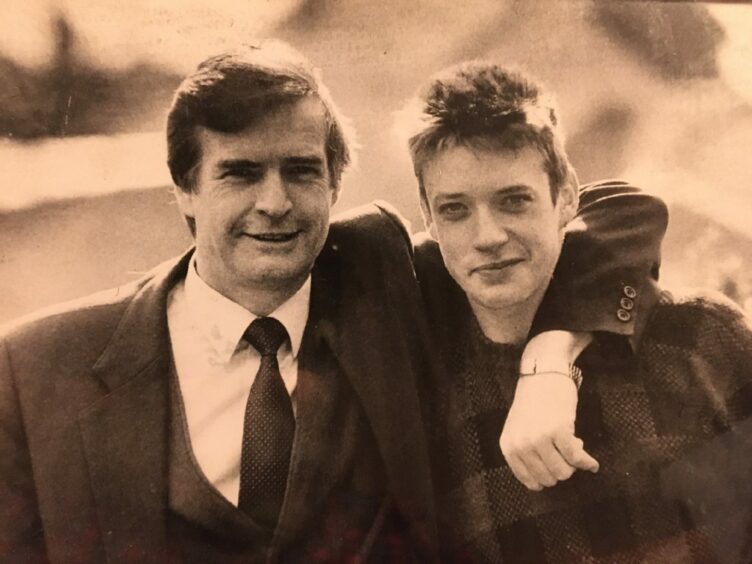

His old man, of course, was William McIlvanney, the writer recognised as the godfather of Tartan Noir, modern Scottish crime fiction. Whether intentional or not, when he introduced him to the rhyme about Cutty Sark, Kirkton Jean and John Barleycorn, McIlvanney senior was setting light to a love of words in his son.

“The octosyllabic couplets are a real mnemonic,” said McIlvanney junior, via Zoom from his family home, revealing a little of the day job as Stuart professor of Scottish studies at the University of Otago. Professor McIlvanney he might be but the kid counting beats of eight in narrative poetry is never far away.

“Dad explained the vocabulary to me and it’s accompanied me through my life,” said McIlvanney, 52. “Sometimes, if I’m bored on a train journey, I do Tam o’ Shanter to myself. It’s always there. Ten or 12 minutes to spare, switch it on and away you go.”

When not reciting Burns, or enlightening Kiwi students as to the riches of words written hundreds of years ago and 11,000 miles away, McIlvanney retreats to a world that would make hairs on even Tam o’ Shanter’s neck rise.

His new novel, The Heretic, is the sequel to 2018’s The Quaker, in which the lead character of a gay, shinty-playing officer from Ballachullish investigates a series of Glasgow murders in the ’60s while trying to keep his personal life on the down-low.

The Quaker was roundly praised, the McIlvanney Prize for Scottish crime book of the year, awarded at the 2018 Bloody Scotland festival, among its laurels. How did it feel winning an award named for his dad? “It was one of the great days in my life,” said the writer. “I was in Stirling with my wife Val, we had a meal, walked up to the award ceremony, got an award, and then finished off the day leading a torchlit procession of all the writers and festival attendees down from the castle through the streets of the old town of Stirling.”

His father, who died in 2015 aged 79, was rarely seen at the head of torchlit processions and McIlvanney laughed as he thought what his dad would have made of it: “He might have lit his fag off one of the torches.”

The Heretic is set in ’70s Glasgow, and McIlvanney is already thinking that part three in the series following DI Duncan McCormack will roll into the early ’80s, perhaps meaning the writer relying less on research and more on memory.

He said: “I was born in ’69, so I’m partly drawing on early memories of being taken to Glasgow as a kid, and relying on research and photographs and newspapers, too. But it’s a very rich archive. You don’t need to go far to find a lot of information about Glasgow in that period, especially if you’re writing from a distance of 11,000 miles.”

With writers like Denise Mina and Alan Parks also plotting their murderous tales in Glasgow’s relatively recent past, which can sometimes seem like a foreign country, what is it about the city’s near-history that draws authors back to its streets?

“Partly the passage of time,” said McIlvanney, whose other books include All The Colours Of The Town. “We are at a sufficient remove where we can look back on that period and assess it. One of the things you’re trying to do is look behind the acceptable facade of society and probe the grittier realities underneath it and, in the case of Glasgow, that lens tends to be a historical lens.

“When I finished my degree in Glasgow we had the City of Culture which created a transformation in the city’s understanding of itself and how outsiders perceived it.

“But if you’re trying to push past that to the gritty realities then one way is to go back to a time before the sandblasting of the tenements, that sense of a more authentic, more ‘noir’ city. Denise Mina’s The Long Drop has that great description of Glasgow ‘accoutred in black like a woman in mourning’.”

McIlvanney draws a parallel with writers in Northern Ireland poring over their recent history. “A very different society, of course. But still that sense that ‘the owl of Minerva flies at dusk.’ The time to understand something is when it’s coming to an end,” he said.

“One of the advantages is not having to worry about mobile phones and that level of connectivity. People have to find a phone box. There’s something quite nice about that slower pace, in terms of the texture of life. It was quite therapeutic to spend some time in that zone even if you’re dealing with murder and mayhem.”

Where The Quaker dealt with murders inspired by the dark mystery of Bible John, McIlvanney was free to let his imagination roam in The Heretic, a world of tenement arson, aggressive polis, sectarian foment and motorways being carved through city communities.

“I didn’t have that central hook, which has its advantages. You don’t need to check if things are accurate. You can just make things up, which is the gig after all.”

McIlvanney is already 50,000 words into his next novel, a psychological thriller set on the Ayrshire coast.

Originally from Kilmarnock, he returned with his wife and children to live in the coastal village of Fairlie for six months in 2018. “It’s a bit like Midsomer,” he said, laughing. “Someone trying to make Fairlie the murder capital of Scotland. I’ll give it a go.”

And he might not be the only one. That paternal literary lineage might span the generations yet. “I’ve four boys and some, quite rightly, would run a mile from the suggestion, but one is showing dangerous signs of wanting to write,” he said. “So it may be that yet another generation of McIlvanney will inflict their imaginative constructions on to the unsuspecting public.”

And will Tam o’ Shanter be to blame? “I’ve missed the boat there already.”

I teach Tartan Noir but not Laidlaw. I’m too close to it

The bloodslick of Scottish noir spills well beyond the work of the last century, says Liam McIlvanney.

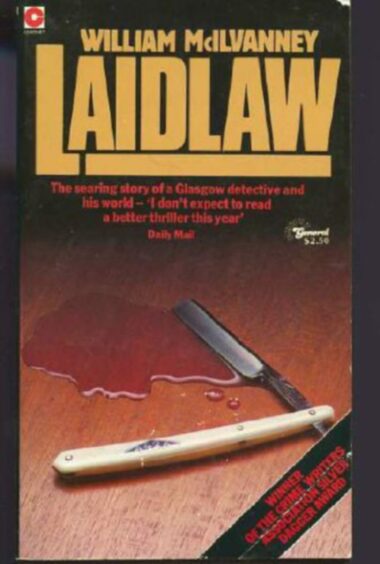

His father’s seminal 1977 book Laidlaw is hailed as the inspiration for the modern Tartan Noir movement spearheaded by the likes of Ian Rankin, Val McDermid and Alan Parks. But McIlvanney sees the roots of the genre extending to a time well before tough ’tecs on the sooty streets of post-industrial Glasgow.

The academic and author, who teaches students about Scottish crime fiction among his papers, said: “Some years I start with Sir Walter Scott’s The Two Drovers as a piece of crime fiction. I’ve had Robert Louis Stephenson’s Kidnapped on there, so I’m taking, I suppose, quite a capacious definition of crime fiction. But it’s interesting how many classic Scottish novels you can teach within the rubric of crime fiction: John Buchan’s The 39 Steps, or Muriel Spark’s The Driver’s Seat, which I teach almost as an anti-crime novel which goes down really well.

“You begin to see Scottish literature as a tradition in which those crime and gothic elements are strong and significant, and it’s no surprise when you look at that history that there’s such a flourishing of crime fiction over the past few decades.

“I teach 10 books on that paper. But not Laidlaw. I’m too close to it.”

The Heretic by Liam McIlvanney, Harper Collins, is out now

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM