Her place in history seems as diminished as it is undeserved; a put-upon wife who succumbed to alcoholism after her explorer husband left her in Scotland to continue his intrepid adventures abroad.

The history books seem about kind as David Livingstone, who, despite their life-long love, once described his wife Mary Moffat as “a little, thick, black-haired girl, sturdy” and an “Irish manufactory” – a reference to her ability to produce children on a regular basis.

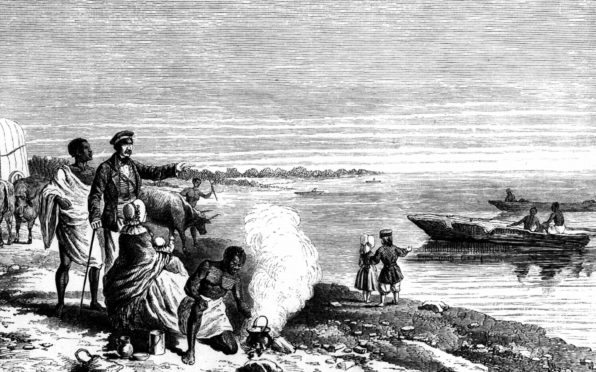

The Blantyre-born Victorian hero choosing to continue his work in uncharted Africa before a more domesticated life with his wife and family has led to her being viewed as a rather dull addendum to the life of her celebrated husband.

However, Mary, who spoke six languages and who was the first European woman to cross the Kalahari Desert – a journey she managed twice, as well as giving birth in the bush on one trip – will be given a more prominent position at the David Livingstone Birthplace museum in Blantyre, Lanarkshire, as part of a £9.1 million revamp.

Dr Kate Simpson, a Glasgow University academic and one of the museum’s trustees, explained: “Visitors will be given a clearer understanding of who she was and what she did, and her role.”

Thanks to animation, she will also be able to speak to visitors to tell her part in the story of one of Scotland’s most famous sons.

Born the oldest of nine children to missionaries Robert and Mary Moffat, she grew up in what is now South Africa. She worked from a young age, fetching water, mending clothes, making butter and soap and generally helping with the daily grind for survival. She trained as a teacher – later, she would run a school with up to 100 pupils – and charmed her future husband, who had vowed never to marry, within days of their meeting at her parents’ missionary station at Kuruman, South Africa, where he was recovering after being attacked by a lion.

Her language skills and knowledge of the country and its people meant she opened doors for Livingstone in places where he would otherwise have encountered hostility and suspicion, and her ability to roll up her sleeves and crack on with backbreaking manual work was key to Livingstone’s success. He called her “the most important member of my team”.

Simpson, an expert in African exploration in the 19th Century, says: “They were married in 1845 and the 10 years afterwards were foundational in establishing Livingstone’s reputation.”

They created three mission stations over the next seven years, each time beginning from scratch, including building their own house. Mary was pregnant for much of the time and with a growing brood to look after.

“She must have had a rod of iron running through her. I always think there is a really interesting Ginger Rogers/Fred Astaire analogy with David and Mary. Everyone always says Ginger did everything backwards and in heels. When David and Mary were doing the original exploration, Mary was always doing it pregnant and looking after children.”

She accompanied him across the Kalahari twice “because she wanted to, because they wanted to be together” but there was a price to pay. Travelling with the three children they had at the time, Livingstone said there wasn’t a square inch on their bodies that hadn’t been bitten by mosquitoes. That first trip ended with her giving birth to a baby, Elizabeth, who only survived six weeks. The following year she was back accompanying him, again pregnant; this time the children almost died of thirst, their tongues turning black. “The idea of them perishing before our eyes was terrible,” Livingstone wrote.

Harangued by his mother-in-law over this treatment of her daughter and grandchildren, Livingstone sent them back to Scotland. It was a sign of how little Mary cared for Western society’s niceties that when she and her children turned up in Cape Town to take the boat back to Britain, William Oswell, a hunter friend of the family, was so horrified to see the state of their clothes he bought them an new wardrobe.

“At this stage Livingstone is only getting £100 per annum from the London Missionary Society which is not enough to support his family in the UK and him on his travels so they are very poor,” says Simpson. She was initially sent to live with Livingstone’s sisters in Lanarkshire which was a culture shock for a woman who had only known life in southern Africa.

“One strongly doesn’t get the impression that she was a meek little wife, she was fairly regularly writing to the directors of the London Missionary Society and various other people asking for money, asking for support of the children,” says Simpson.

“It seems like the alcohol was a way of coping with the horrific stress she was under of trying to have her children educated, keep a roof over their heads, also being desperately worried about David.

“As soon as she gets the chance to come back out and spend time with Livingstone, she does, she is there like a shot. But if you know anything from the small amounts of communication between them, they dearly loved each other.”

“I can say truly, my dearest, that I loved you when I married you, and the longer I lived with you, I loved you the better,” Livingstone once wrote to her. She died of malaria in 1862, aged 41, accompanying her husband on a trip to the Zambezi and is buried in Africa. “I am left alone in the world by one whom I felt to be a part of myself,” wrote Livingstone.

“Hers is a very human story of a very robust independent woman who has somehow become this short, fat woman that we don’t like,” says Dr Simpson. “Yet she was really quite the renegade. I think she should just be remembered and I think we should acknowledge how powerful she was.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe

© Alamy Stock Photo

© Alamy Stock Photo