It was only a few weeks after Scotland’s first case of Covid-19 was confirmed that dentist Grant McIntyre began feeling ill. Admitted to Dundee’s Ninewells Hospital, his condition rapidly deteriorated and he was moved to intensive care.

It would be 128 days before Grant, clinical director of the Hospital Dental Services at NHS Tayside, left hospital, 86 of them spent in intensive care, thought to be the longest ICU stay of any Scottish patient, and 50 of them spent in a coma.

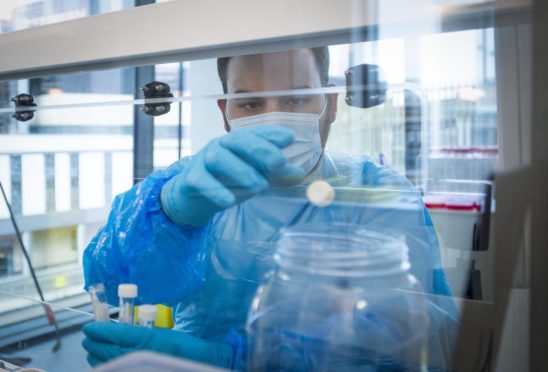

On April 7 Grant he was transferred from Dundee to Aberdeen Royal Infirmary’s ECMO unit, where his blood was circulated through an artificial lung before being pumped back into his body.

He was also given kidney dialysis to give help his kidneys, which were failing as a result of his immune system going into overdrive. Grant returned to Ninewells on May 20.

He was released on August 6 and, here, he and some of the medical professionals who helped save his life describe an astonishing survival story.

Grant McIntyre, survivor

A few weeks before I became ill, dental colleagues and I had been planning our response to the virus unfolding in China. We thought we needed to stop all aerosol generating procedures, but those at the very top told us to carry on as normal when all the information coming to us suggested a halt.

So we took a middle ground to avoid but not not completely stop, AGPs, fearing that we were not taking right and safe action.

By mid March I noticed colleagues with flu symptoms which we would normally brush off as seasonal cold or flu.

A day or so later I lost my appetite, sense of smell and taste and felt exhausted. I called in sick for the first time in 27 years.

I thought I was having a serious attack of childhood asthma and my family called for an ambulance. I was taken to hospital, discharged, readmitted two days later but recovered and released. But I deteriorated, was admitted again – though I have no memory of that.

I do remember a bizarre out-of-body experience of floating above the bed looking at a lifeless body below and when I realised it was me, I fought it. I focussed on every breath because my life depended on it.

I remember the consultant in respiratory medicine waiting there in the middle of the night as I was having a chest x-ray. It was odd because results are usually sent to them the following day, so this could only mean bad news.

I was very aware that I was dying and asked the consultant if continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) breathing would help. They were planning the same.

Within minutes I was being transferred to High Dependency but none of that treatment worked and I was transferred to ICU.

There, two consultants approached my bed in full PPE and said, ‘Right, are we ready to go?’ I was then anaesthetised and that was the last thing I remember until waking up in Ninewells weeks later.

It feels strange to have been unconscious for 50 days and not being aware of any of it. I’m told I managed to lift fingers and speak briefly to my son on his 21st birthday, but I have no memory of this.

I didn’t know where I was, who I was, or any of the people around me. I didn’t know if it was day or night because the area had been requisitioned from a theatre recovery suite where there were no windows.

I began to have some strange and unhealthy thoughts. The walls and ceiling moved inwards and out, animals appeared above me. Constant visions of a python trying to wrap itself around my chest and suffocate me then appeared.

I then confused the team trying to save me – the intubation tube – as someone trying to kill me and everyone did their best to comfort and reassure.

My mental health was not as it should be after Covid, and sessions with a clinical psychologist were hugely helpful.

Eventually I was wheeled out of the ward to see my wife, Amanda.

I will never forget that moment or the all the NHS professionals who made it possible.

Tom Fardon, respiratory consultant at Ninewells

Grant was only 48 and was the youngest patient by far in an eight-bed Covid unit filled mostly with men in their 70s and 80s.

We had not seen someone so otherwise healthy become so unwell with Covid in those early days of the pandemic. I knew Grant was a colleague and was worried about how quickly he was deteriorating. We were dealing with a virus we had never seen or treated before and there were no textbooks of references for treatment.

Tests showed that he had severe Covid illness, and as he declined we upped his oxygen again and again. Initially he improved and then declined quickly, a pattern we see so often with Covid.

We knew he was at serious risk, but we hid those feelings as you always try to give the patient hope and confidence but nothing we had in our usual armoury of drugs was working and we called for help from ICU. After a team meeting with colleagues there, Grant was quickly transferred and anaesthetised before being intubated.

However, the feedback from colleagues there was that he was becoming sicker. Grant had cytokine storm syndrome where the body’s immune system goes into overdrive, and can attack its own organs.

They too, were running out of treatment options and knew that the last option was a treatment called ECMO (extra corporeal membrane oxygenation) at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary. Twelve days after he was admitted to Ninewells, a team came down from Aberdeen and transferred him there.

The Aberdeen team kept us updated on Grant’s progress. While it wasn’t always good news, he was surviving. When he returned from Aberdeen he was exhausted and could not lift even a finger. He had lost huge amounts of muscle, which happens to patients after weeks immobilised on ECMO and in ICU.

We then had to bring him out of is coma – which he had been in for 50 days. As patients gradually emerge they can hallucinate experiencing terrifying images and Grant did.

We spent a lot of time with Grant talking him through this, sorting out reality from hallucinations,

After a spell in our ICU then High Dependency, Grant was transferred to a lower intensity ward for rehabilitation.

He had survived against all the odds.

Lee Allen, ICU specialist at Aberdeen Royal Infirmary

The ECMO treatment we started giving Grant prevented him from dying, but despite all our efforts he remained critical with little – if any signs – of improvement.

At this point I remember lengthy discussions about the pros and cons of giving him high use steroids. The potential benefit was to dampen lung inflammation caused by Covid-19 but if he had any bacterial infection it would accelerate and overwhelm him.

The decision was made to go ahead and we monitored him closely. Fortunately, he began to show some signs of improvement and we gave him another dose. After the second round of steroids he continued to improve.

Covid-19 was completely new territory for us and we were very much learning on our feet and I was not quite ready to feel hopeful.

Then one morning when I came into work Grant was being lifted out of bed and onto a chair by the nurses and the physiotherapists and I thought: “This guy might just get away with this. He might just make it.”

Until then we weren’t sure he would, so it was a moment of sheer joy for us all. In the seven weeks with us we had got to know his family and so much about his life, as we do all our long term patients.

Before the pandemic families were able to visit and we could console, explain and support them when news is bad. With Covid it is all done over the phone and so when our patients die it is hugely upsetting for everyone.

We have endured this for almost a year now and patients continue to be younger younger and sicker than anything the hospital has seen in living memory.

When Grant was eventually wheeled out of ICU to head back to Ninewells we all felt we had achieved something amazing.

Sara Matthews, physiotherapy team lead at Ninewells

We knew that recovery from Covid would be very slow but there was a way back.

Even as Grant lay anaesthetised, we were stretching his ankles, feet spine, shoulders for a few minutes at a time.

After a week he regained consciousness. He was profoundly weak and moving one finger was exhausting for him but we had to get what we call the neural pathways working again and get his body used to moving.

As patients lie in a coma their brains are not constantly responding to signals to move our bodies. Repetition of physio helps establish that link again.

Grant was one of the most challenging and the first steps of physio were incredibly difficult.

He was the sickest of patients to survive Covid and we had a few like Grant who progressed and then deteriorated which was heartbreaking to their families and us.

Sometimes a patient would look across the ward in the morning and ask where another one was and we would say they had moved to another area of the hospital, when in fact they had died suddenly.

Grant had ICU Acquired Weakness. Even moving his hand to his face was a struggle. It was vital to get Grant out of bed and onto a table which he named “The Table of Torture”

It gently moves to allow the patient to stand upright but Grant felt very dizzy, more than most patients, and pleaded to be put back into bed. While he argued and pleaded to be put back in bed the allotted five minutes standing had passed.

We needed to get him and other patients to carry their own weight again and help their blood pressure adjust to standing up.

Those five minutes arguing were a huge breakthrough because after that, he would tell us he was capable of more than that, as if he was challenging himself.

One weekend when his wife Amanda came to see him, he had completed so much physio and exercise that he slept through her visit and much of that weekend.

He set all these targets for himself – 43 days in ECMO, 43 days in ICU and 43 days in rehabilitation. He beat the last by a day.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Mhairi Edwards

© Mhairi Edwards

© NEWSLINE MEDIA LIMITED

© NEWSLINE MEDIA LIMITED © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM