It has been a haven of quiet solitude and study for more than a century but when inspiration struck artist Elizabeth Price in the world-famous Mitchell Library it came from the floor not the book shelves.

The Turner Prize winner was awestruck by the floor coverings in one of Glasgow’s most iconic buildings and the textiles, with their hypnotic designs and psychedelic patterns which, she says, offer “an optical intensity” not commonly found in public buildings.

Inspiring her latest art work, the spectacular free-wheeling carpets are, she said, the physical embodiment of a free-wheeling thirst for knowledge, ideas and discovery.

“The carpets were so unusual to have in a library building,” she said. “They almost constitute a form of diversion or distraction. I became carried away with the idea that the carpets alluded to a much more optimistic idea of a shared culture; the idea of an imaginative transportation through knowledge.

“We think of knowledge in such limited, misanthropic ways; that we need to learn skills in order to be productive and aid growth. Libraries and universities feel increasingly reductive as to what knowledge is for, but going into this library there was a sense it was for pleasure and imagination and ideas.

“I also really loved its music carrels – spaces within it for the making of sounds – which is such a brilliant and generous proposition in a library, to have musical instruments. The original library design also had an area for painting, with splash areas. The idea it would be a creative space to make things, to be recreational, I think the carpets are a part of that.

“Sadly, there is a lost sense of generosity and optimism in civics but not in Glasgow; I think this is maybe one of the last buildings that has held its potential users in such high esteem.”

What led Price to the Mitchell Library was a commission focusing on the textile heritage of Glasgow’s industrial age, in particular James Templeton & Co Ltd and Stoddard International Plc, world-famous carpet manufacturers in the city and nearby Renfrew that once employed thousands of locals.

The result, Underfoot, is Price’s first solo exhibition in Scotland, opening at The Hunterian museum on Friday. It comprises a new moving image work as well as a bespoke textile piece – a rug named Sad Carrel – which is her first.

She was approached by writer and artist Fiona Jardine, from the Glasgow School of Art, with the carpet commission. “I found it an unusual proposition and I was fascinated by it,” continued Price. “The subject matter of a lot of the films I make is textiles, partially because I’m interested in the shared history between woven textiles and computing, but also by the cultural history of different textiles.

“I was captivated by the archive of carpet designs Fiona told me about. I had no knowledge of Templeton but going through their archives I recognised a number of designs from my childhood and my parents’ house. To see the painted design that preceded the production of the carpet from our living room gave a little jolt when I saw it in the archives.”

A research fellowship with the University of Glasgow Library gave Price access to the vast archives of the Templeton and Stoddard factories that are held there, and the knowledge of researcher Jonathan Cleaver, who had completed a PhD on the archives, which includes sketches, carpet pieces, books, journals and photographic records of the industrial manufacturing processes.

Price, from Bradford, explained: “I’m always interested in the relationship between cultural objects and art and design objects, and social history.

“Workforces become almost the most important thing – they are the main protagonists of the social story. There are some amazing pictures in the archives of the workers. I’ve always been fascinated by gender politics in workplaces, so it was interesting to see the role women had here and I became fascinated by this loom called a Spool Axminster.

“One of the reasons it was developed and why Templeton bought one was because it could be run by women, and it was possible to pay them less, so there was a profit incentive. It had other attributes as well, like being able to have an infinite amount of colours. It was an amazing thing, with all of these yarns wound on to separate spools, with a lot of young women winding the spools as if they were data importers of an image. It was a breaking down of the processes and a particular role for women.

“It was in order to accommodate the loom that the famous building at Templeton On The Green was built, because these loops of spool can run for metres and metres – either above the head and across the ceiling laterally, or vertically up several storeys, so a steel-framed building was required.

“The looms look bonkers. Quite inelegant, big machines that were invented to recreate artefacts made through a handmade process.”

James Templeton was a farmer’s son who was born in Campbeltown and came to Glasgow as a youth to work in a draper’s shop. He was able to start his own business after a financially-rewarding stint in Mexico and returned home, initially opening a shawl company in Paisley and then a carpet factory in the Bridgeton area of Glasgow in 1839.

The company’s famous building opposite Glasgow Green, based on Doge’s Palace in Venice, was built 50 years later. The Bridgeton factory closed in 1979 and the Venetian building later became a business centre.

Price, who also collaborated with curatorial company Panel on the commission, said: “An awful lot of the things made by Templetons were extraordinarily expensive for most people in the middle part of the century but they were more accessible by the ‘70s or ‘80s.

We had lino in most rooms growing up, apart from the living room. I saw photos of the women on their hands and knees, grooming the carpets by hand; these big, luxurious carpets for a gentlemen’s club being trimmed by young Scottish women with tiny pairs of scissors.

The images showed a physical, intimate relationship of labour and presumably some pleasure and pride, but also of an alienation and sense of limited access to them.”

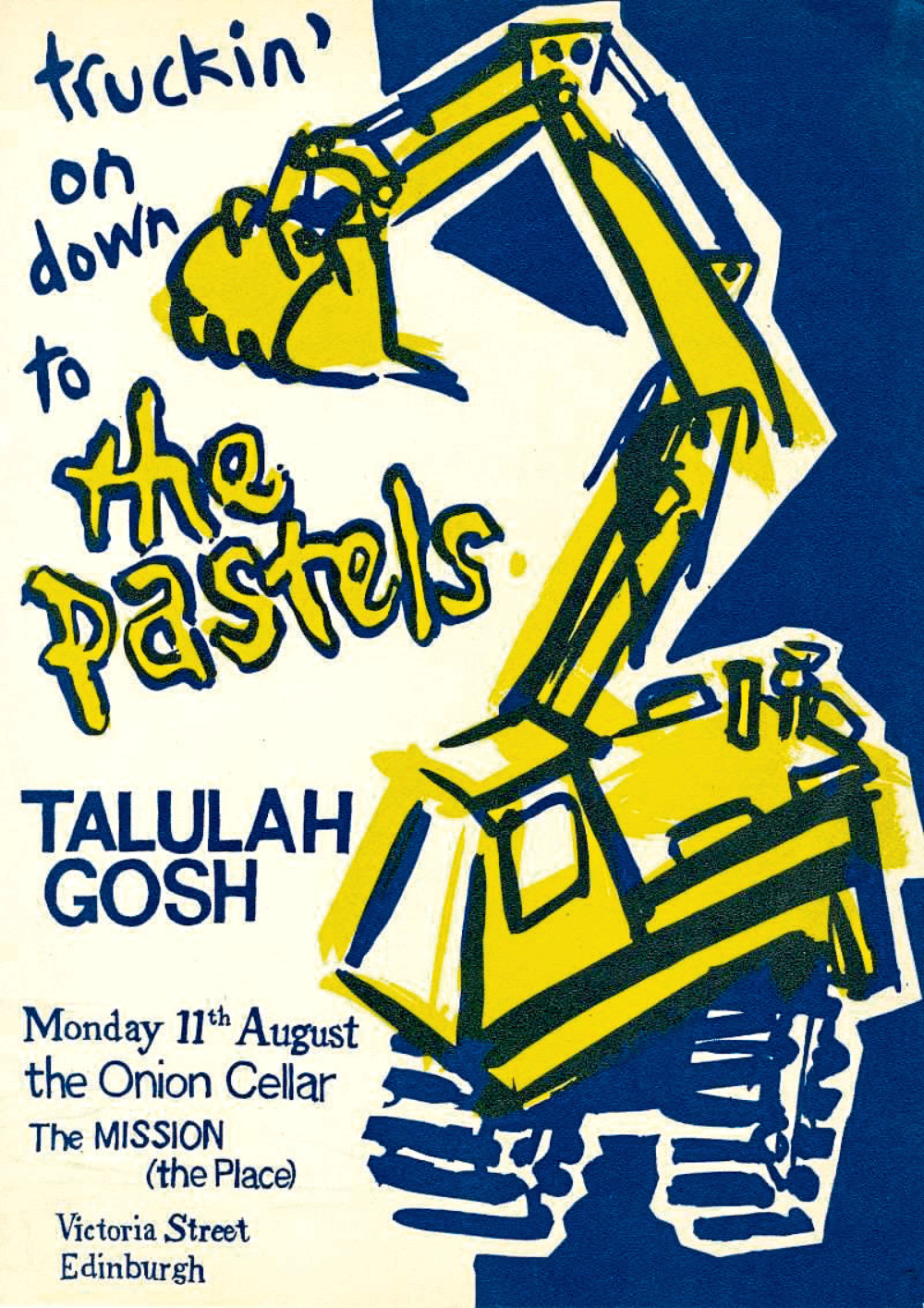

A former musician with indie bands Talulah Gosh and The Carousel, Price had only been making videos for six years when she won the Turner Prize in 2012 for The Woolworths Choir of 1979, which featured stitched together news footage of a fatal fire in a Manchester branch of the chain store alongside a TV performance by the Shangri-Las and digital animations analysing the culture and political relationships between the two, to profound effect.

“It was a bit of a shock,” Price recalled, 10 years on from her win. “I was nominated for my first museum show, so everything happened overnight. It was a bit mad. It makes things a lot easier economically and I found I wasn’t scrapping around so much and not living on peas on toast at the end of the month.”

Making the rug, which she did with Dovecot Studios, was outside her area of expertise but she found it a rewarding experience.

“It was a real learning curve and a slow process in terms of understanding exactly how it would work, as far as mixing different colours and providing it with the lustre I wanted. Another challenge came from researching industrially-made carpets but the one I was making was a unique handmade tufted rug, which employs completely different processes. I wanted to make sure it was clear they were different things.

“My video relates more to the industrial carpets than the rug does. I took one of the designs from the Mitchell’s music library – discs intended to represent vinyl records, which was my favourite design – and developed a variation on that. The rug is a handmade rendition of an industrially-made original – I wanted to point out and reconcile the differences between the two technologies.”

Price, who will also have a separate exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art in Glasgow in January, was inspired by the city and her past connection to it when it came to forming the soundtrack for the video installation of Underfoot.

“I came to Glasgow when I was 18 in a band, where we played with The Shop Assistants and The Pastels, so I have all of these sentimental connections to the city from the ‘80s.

“The video features a lot of guitar sounds and I’ve never really used guitar in any of my videos before, but it’s there partly because of my significance to it in the city but also because of Glasgow’s music scene. Apparently bands have used the Mitchell Library’s carrels to rehearse in, too, so there were all of these different connections.

“There’s a little section in the film that discusses the origin of the word carrel – it’s a medieval word related to monks’ enclosures but it also comes from the same origin as carol, a festive song. I was fascinated by the idea that these monks’ enclosures are intended to shut out the world but also synonymous with song and other voices.

“I always like coming across new words. The etymologies are often fascinating or complex like that, with the word containing within it almost oppositional ideas.”

Underfoot is at The Hunterian, Glasgow, from November 11 to April 16

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © ANL/Shutterstock

© ANL/Shutterstock © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM