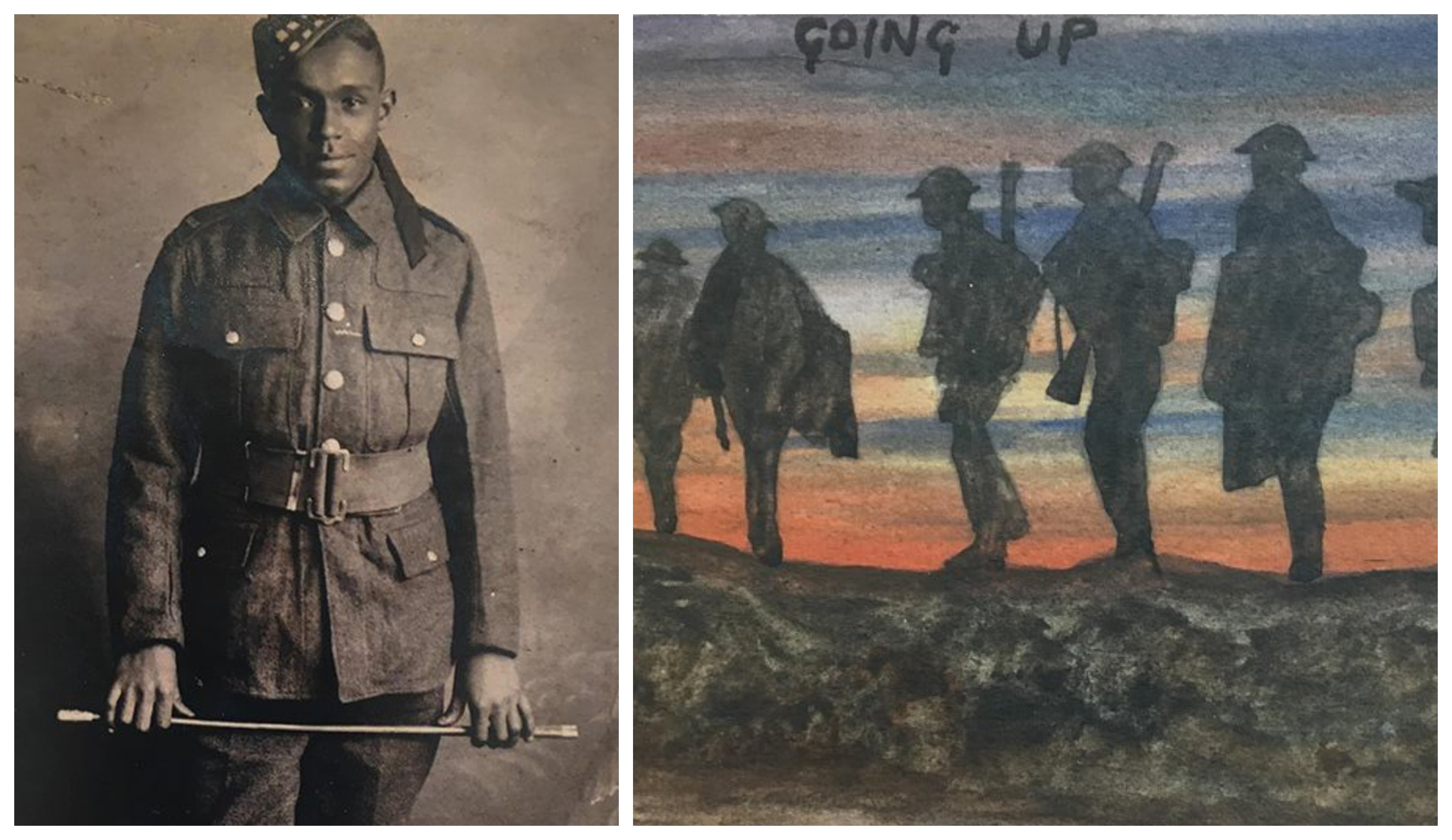

SCOTLAND’S makar Jackie Kay has saluted a forgotten Scottish soldier in poems inspired by his haunting diaries.

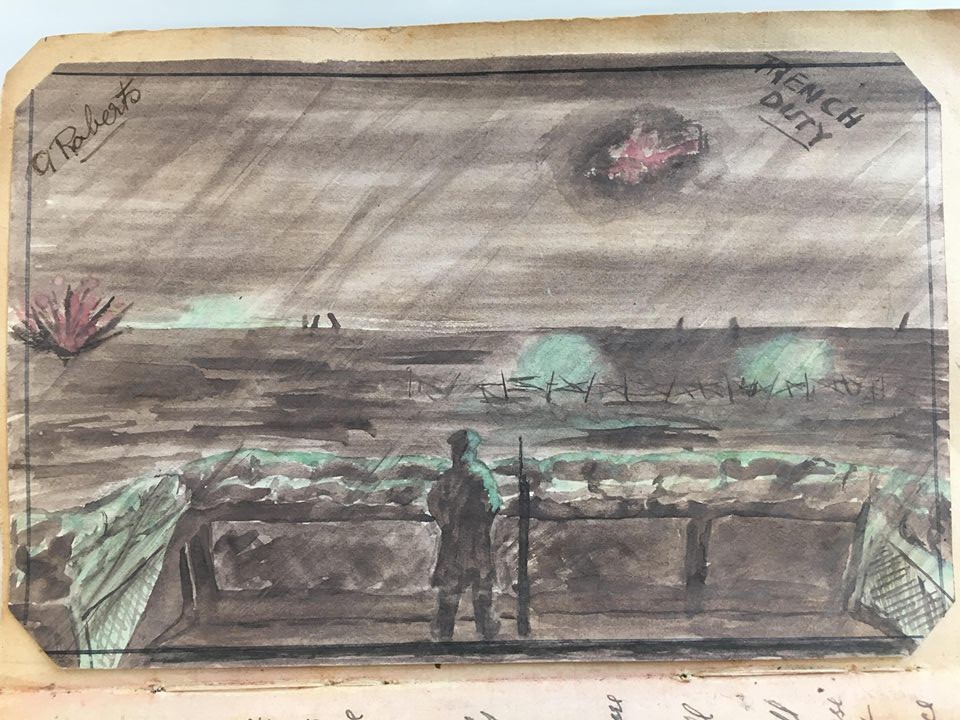

Before Remembrance Sunday, our national poet has told how a box of notes, photos, drawings and letters documenting Arthur Roberts’ experience in the trenches during the First World War led her to write six special poems.

The documents – which were found by chance in an attic in a house in Glasgow in 2006 – were later published in a book and have now been turned into a documentary.

The programme points out no black troops were included in the Peace March in 1919, when thousands of troops marched through London to celebrate the end of the war.

He was one of thousands of black soldiers who fought for Britain in the First World War but whose bravery went unacknowledged, according to the poet,

Kay said: “It is outrageous and appalling and makes you feel a bit ashamed. People gave massively to this country and to have not a single black face in the victory parade is shocking.”

She added: “For a lot of soldiers what they saw was so horrific the stories got lost in that way, because they weren’t able to tell them.

“We don’t want the stories being lost twice, so where we can remember, where we can bring people like Arthur Roberts to the fore, it is good for the generations to come to know of that kind of sacrifice and to know that people were forgotten – particularly black and Asian soldiers.

“In the light of what has gone on with the Windrush generation and the scandal of that, it feels ever more resonant.”

The BBC 4 programme, to be shown next month, uses Roberts’ own words to tell his story – from getting his first love letter and going to dances, to his fears before going over the top and the horror of witnessing comrades dying.

Kay narrates A Scottish Soldier and reads her poems specially written for it. She said it was “miraculous” the soldier’s story had not been lost forever.

She said: “If different people had found that diary, they might not have had an interest or realised its worth – it might just have been thrown out. So it could not have been found, and had it not been, we would never have known the story of Arthur Roberts.

“The amount of chance and circumstance that is in there makes the story quite electrifying.

“It also feels really sad for Arthur that he wrote that diary with the intention of it being published – and it’s sad he never got to see that.

“But hopefully somewhere he is smiling and savvy to what is going on. The film is a homage to Arthur, and also a way of keeping Arthur – and men like him – in the public view and alive.”

Arthur, whose father was from the Caribbean, was one of thousands of black soldiers who fought for Britain in the First World War, but whose contribution has been long been overlooked.

Arthur’s diaries were found in the attic of a house which was bought by Murray Miller.

His mother Morag subsequently began researching the soldier’s story.

Arthur was born in Bristol and moved to Glasgow with his family when he was around seven years old and became an engineering apprentice in the shipyards aged 18.

He enlisted in February 1917, and his diaries bring to life the horrors he and his comrades endured.

In one entry he speaks of the damage caused to trenches by heavy shelling adding: “the dead men were often so numerous it was impossible to proceed without walking on them”.

He relates a horrific moment a corporal caught a “whizz-bang” – slang for a shell – writing: “He fell on the food rations, covering them with blood, so now we can’t eat them.”

The diary stops in 1918. After the war, Arthur returned to Glasgow and the Harland and Wolff shipyard to finish his apprenticeship.

Details of his later life are patchy, but he fell in love with and married Jessie Finnigan.

Arthur moved himself into a care home in Glasgow in 1979 and died three years later.

Clara Glynn, of Hopscotch Films, who directed and produced the documentary, said his care worker Allison O’Neill had recounted how Arthur would refuse to watch coverage of Remembrance Day on television.

She said: “Allison said he would just take himself off to his room and not want to watch it and be upset by it. When war films were on he would also get really cross and say that they had no idea what it was like.”

But she added: “Allison said to me she thought that if Arthur could see her talking about him in the programme he would be dancing a little jig, he would have loved it.

“This amazing guy is now someone who people will know about.

“When I read the poems, I thought they were amazing, especially Remembrance Sunday; it so captured Arthur.”

Just one everyday hero

Here, in two of her six new poems, Makar Jackie Kay hails the courage of Arthur Roberts in the hell of war and remembers a brave but forgotten life.

The Moon’s Eye

You were frightened that you would become afraid

And that fear would strip it all away-

Your uniform, the boots, the patriotism,

Your unit, the bravery, the sense of a mission.

And waiting up ahead on the frontline, fear itself,

Quaking and trembling, all legs and ankles.

Till you were feart

Stripped of everything, naked as the day you

Emerged, a small boy out of the womb

With no sense, slipping out of that cocoon

Of the fire or the trenches or the stench.

That men would kill and kill again

That lives would count for naught

Under the watchful eye of the moon.

Remembrance Sunday

Remembrance Sunday

A day when paradoxically

He felt forgotten

Not like that Monday

When the shop steward

called him a black b******

Or Tuesday

When he watched them fish

The suicides out of the Clyde

Not like Wednesday

When Cupid’s arrow

Sailed over his head.

Or Thursday when Alison

warmed up olive oil,

massaging his trench feet

Not like Friday

When they blanked his dark face

From the Victory Parade

Or Saturday

When he danced alone

In his room with a Zimmer

But Remembrance Sunday

When no one remembered him

And he hardly remembered himself.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe