With paper and pencil, he ventured forth to draw his country and, 400 years later, the work of Timothy Pont, the man who mapped Scotland, is to be celebrated at a new exhibition.

While our phones politely tell us when we make a wrong turn and satnav steers us safely to our destinations, it is easy to imagine never unfolding a paper map again. Easy but wrong, according to Chris Fleet, map curator for National Libraries of Scotland.

He said: “Maps are still very much used now, probably more than ever. There seems to be a belief that paper maps are going to die soon but maps are as important today as they ever were and we won’t see that era of mapping, whether printed or digital, coming to an end any time soon.”

Fleet, who has worked at NLS for almost 30 years digitising maps old and new, is looking forward to unveiling some of the earliest surviving detailed maps of Scotland in a new exhibition, Treasures, showcasing some of NLS’s most precious pieces.

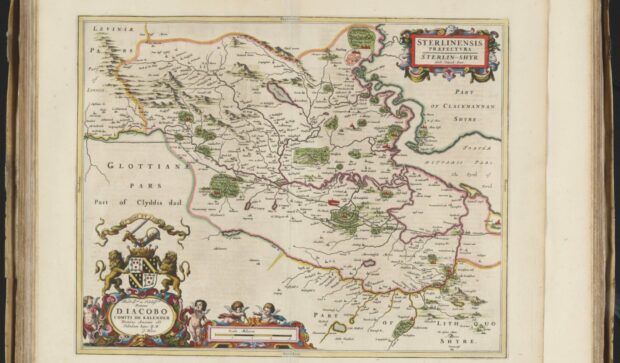

The maps, created by Pont more than 400 years ago, can be used to chart geography of 16th-Century Scotland as well as its history, landscape and architecture.

Fleet said: “In the 1560s, the maps of Scotland that existed only showed around 120 place names, such as Edinburgh, St Andrews and Iona. After Pont did his work, we have over 20,000.”

There are 77 of Pont’s surviving maps on 38 sheets of paper, all of which are held in NLS’s collection.

“Pont’s map-making really began in the 1580s,” Fleet said. “What we know is that he was probably born in the 1560s. We know that he studied at St Andrews between 1580 and 1583. His father was a very influential churchman, moderator of the General Assembly of Scotland five times. He was able to grant lands to Timothy north of Dundee, giving him an income. Pont, who was married with two children, became a minister for the parish of Dunnet in Caithness in 1601.

“His wife is described as a widow by 1614, so we know he died around 1614 or before. Most of his maps are undated but we think he put them together between 1583 and 1614.

“It’s clear when you look at them that they were not made through accurate surveys using trigonometry, which was regularly used in Scotland from the 18th Century.

“If you have a theodolite, which can measure the angle between two different points, and have a measured distance, then the lengths of the other sides of the triangle can be computed through trigonometry. This is how Ordnance Survey maps were made and many accurate maps in the 18th Century were made.

“They measured a base line then measured angles across the country from one mountain top to another then they knew accurately the distances between them without needing to measure these distances on the ground.

“Pont didn’t do that. We think he spoke to people who would tell him ‘If you follow this river, this place is five miles on the left bank and then that place is two miles on the right bank.

“Quite often, the general distance is accurate and the general direction is okay but they couldn’t be placed on top of a modern-day map and match it.”

Pont’s maps show the detail of the 16th-Century landscape. They show the detail of tower houses and castles, smaller buildings and settlements, mills and rivers and the extent of woodland and physical features such as rivers and valleys and mountain tops. They also mention landowners and other people.

“Maps are never just a copy of everything that’s out there. Map makers decide what to put in and what to leave out. Depending on who is making these decisions, different things get put in or left out. It’s all in the perspective of the map maker,” he said. “Pont was really interested in mapping the country for an audience of wealthy Europeans. The people who would purchase maps in Pont’s time were not the average man or woman on the street.”

Relatively few people in Pont’s time were able to buy or even read books. The maps were produced for very sumptuous, expensive atlases – for people like kings and queens, the aristocracy or wealthy merchants.

When Pont’s maps were printed into an atlas, most of the content was written text. For example, Blaeu’s Atlas of Scotland (1654) which included Pont’s maps has 48 maps and 154 pages of text.

“Pont’s maps in the atlas were accompanied by written text that described the cultural region, foodstuffs, great marvels and mysteries and anecdotes and folklore,” said Fleet. “They helped people visualise another country that was exotic and interesting. It wasn’t something that was going to be used for travel. It was really for their private libraries, so they could view something splendid.

Of course, over the next four centuries, maps evolved, but Fleet says progress has been halting. “Maps weren’t a continuous progress at all, but very much stop and start.”

After Pont’s time, it wasn’t until the 1680s that John Adair tried to update Pont’s work. “Military mapping came with the Jacobite Uprisings in 1715 and 1745. And between the 1760s and 1840s mapping was produced to support a wave of agricultural improvements,” said Fleet. “In the 1840s, Ordnance Survey began mapping, which is quite late after Pont made a start 400 years ago. Their maps are by far the most comprehensive ones of Scotland and they are revised at regular intervals right up to the present day. They are of great value. These are often the first maps people look at when they go back in time.

“There hasn’t really been an even rate of progress over time. Activity has been based on different perspectives at different times, and that’s what makes Scotland’s mapping history so interesting.

“It’s convenient now for people to be able to look at maps on a screen, but in many ways there’s more of an excitement about seeing these things in reality,” he said.

Treasures, National Libraries of Scotland opens on Friday

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe