She was the American socialite who swapped the high life for a far harder life helping to protect and preserve ancient island culture in the Outer Hebrides.

Margaret Fay Shaw, a steel magnate’s daughter and talented concert pianist, swapped the States for South Uist in the 1920s and, working alongside islanders, hauling seaweed, milking the cows, and “waulking the tweed”, the Manhattan musician absorbed the language and culture of the island.

More importantly, she was the first person to transcribe its traditional music, saving in written form songs that had been passed orally from generation to generation. Her lifetime collection – bolstered by her photography, letters and diaries and, together with recordings later made with her husband, John Lorne Campbell, a historian, folklorist and farmer – is said to be the most significant in the preservation of Scotland’s Gaelic culture.

But, 17 years after her death, archivist Fiona J Mackenzie has revealed new finds, a letter and diary entries shedding new light on the life of an extraordinary woman.

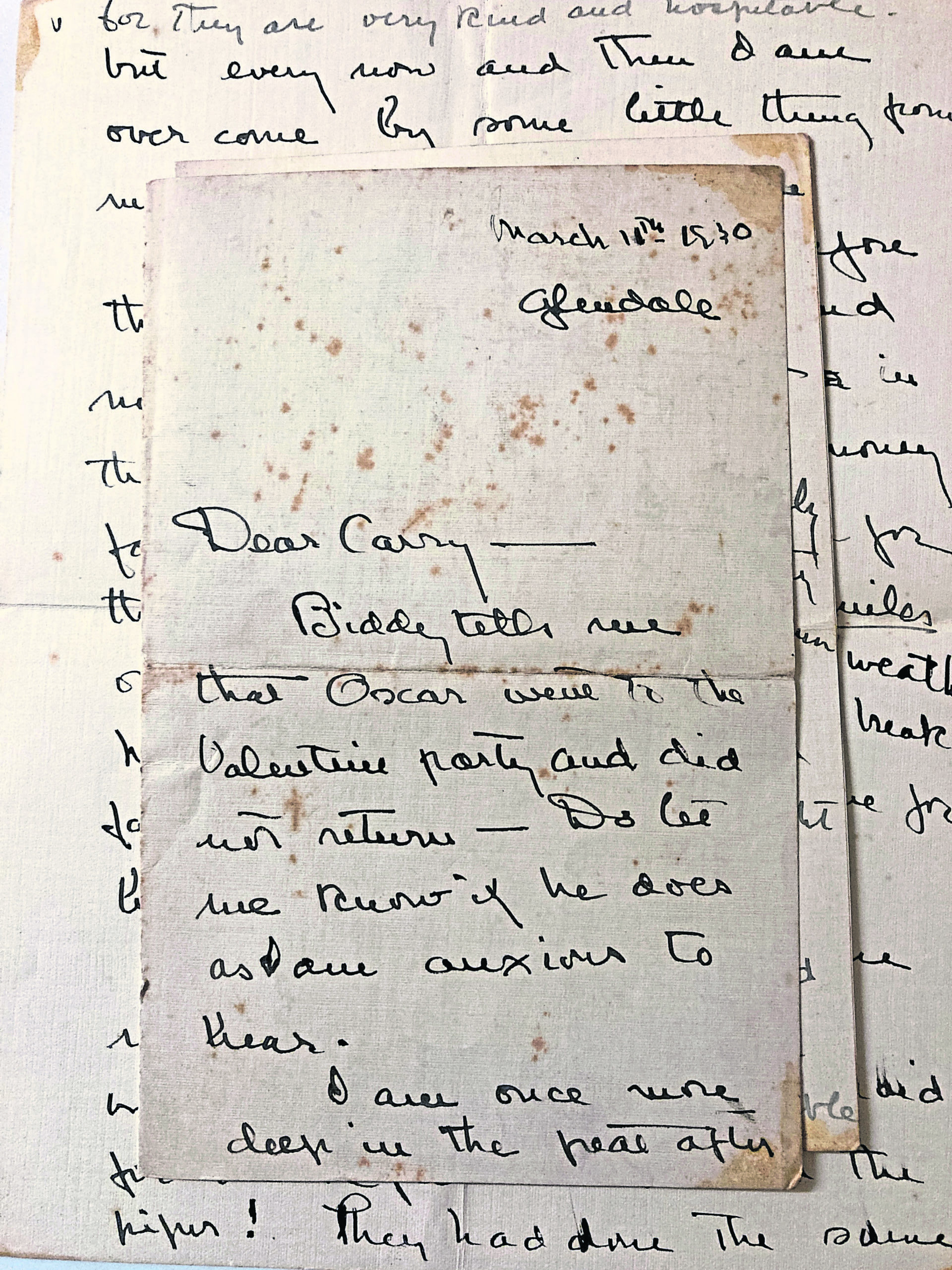

Fiona said: “A previously unseen letter that Margaret wrote to her sister Caroline from North Glendale on March 11, 1930, was given to me by her great niece in America, Maggie Van Hafton.

“This letter has never before seen the light of day. We also have some original diary entries that have never been published. Margaret Fay Shaw is right at the top in terms of significance to the preservation of a culture. Had she not done the work that she did, it would be largely lost.”

Fiona is based on the island of Canna bought by the Campbells three years after their marriage in 1935. John, who died in 1996 aged 89, and Margaret, who passed away in 2004 aged 101, gifted the island and the home in which their cherished collection was housed to the National Trust for Scotland.

Here, in an extract from the found letter of Margaret Fay Shaw to her sister Caroline and dated March 11, 1930, she recounts raising funds to give pupils at the school a warm drink.

I think I told you before that the school teachers and myself gave a dance in the school house to get money for a hot drink at lunch for the scholars who walk miles over the moor in terrible weather, half the time with too little breakfast and one piece of scone for lunch.

Kay had sent some money at that time and with some of my own I paid for the refreshments and the piper! They had done the same thing on the other side of the loch with the local intelligentsia and got much more money, of course.

This school is really Mr Ferguson’s property and most of the children belong to men who are working or have worked for him. He bought one ticket at 1/6, about 30 cents, and said he had some cocoa which he hadn’t been able to sell in the shop – he had had it three years – and he would give it to us. But he couldn’t find it so we’ve been buying it until he does! And from Mr Gillies’ shop I bought nearly $30 worth of stuff for these treats and by George he charged me four pence for some little paper bags to put candy in.

I got a good deal of Christmas money and was able to do a lot of little things for some souls and they have been mighty kind to me. I have about six pairs of woollen socks, six yards of lovely tweed and a piece of delicate material that is very nice, and a wooden stool besides the songs and poems which are as much of a gift. Even hens and two dozen eggs. And all this from people who haven’t any money. This isn’t mentioning wild fowl (poached at that!), lobsters, crabs and what not.

I am sitting at the table in my room clad in flannel pyjamas which are the rendezvous of fleadom – every now and again I turn my coat inside out and shake, to no effect. I caught one, however. The one thought against staying on after May is earwigs which flood the place. I remember being terribly bitten in Mrs Campbells cottage last year and I am told this side of the loch is much worse. I really must go to bed as it is nearly 2am. Much, much love to everybody and write soon to your affectionate

Maggy.

Don’t let anybody read this letter who might get the idea I was trying to appear as Miss Give All!

The archivist explained: “Her Gaelic work is unsurpassed in terms of the physical writing down of that oral history. She was the first person who possessed the musical education to be able to write down songs never before written down. She had a good ear; she could understand the musical notes and strange intervals present in Gaelic tunes.

“At the same as writing them down, she was taking photographic images of the people who were giving them to her. And she was writing about and corresponding with them. There are also artefacts. What we have is not just one isolated piece of heritage, but a big jigsaw where every piece fits.”

Margaret Fay Shaw’s great-great-grandfather, Inverness man Alexander Shaw, who worked for the Carron Company ironworks at Falkirk, sailed with his four sons from Gourock to Philidelphia in 1782. Most of the family then set up businesses in Pittsburgh. But Margaret’s parents died while she was still a child, leaving her and her older sisters in the care of aunts.

In 1920 she was sent to Helensburgh to spend a year at St Bride’s School where, during a concert, she heard Marjory Kennedy-Fraser singing her “Songs of the Hebrides” in grand Victorian style and with florid piano accompaniment. Margaret later said she longed “to hear these songs sound like they were when they were first heard; when they were pristine, the real thing”.

She got her chance a few years later in between her training as a concert pianist in London, New York and Paris under the inimitable charge of the revered conductor, composer and teacher Nadia Boulanger. Margaret took time out for a bicycle tour in the Western Isles. It was the beginning of a lifelong Hebridean love affair.

Back on home turf and after a bout of depression following a diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis that put paid to her concert career, she upped sticks and relocated to South Uist. The 1929 move – much to her family’s horror – saw her going to live with Mairi and Peiggi Macrae in a tiny cottage without water or electricity.

Margaret later described herself as “a little bird blown off course” but confessed: “I have never felt better, nor was I ever so happy.”

She described her arrival on the island in an archived recording: “In the very moment of my arrival I began to learn; first to do without. There were no green vegetables or fruits. My clothes were the wrong suit and my shoes leaked. I have never known such wind…”

Fiona, a professional singer acclaimed at the Mod, the festival of gaelic music, said: “She was a socialite. She came from steel stock. The family had money and that’s partly why they didn’t understand Margaret’s passion and desire to immerse herself in what they perceived at the time as life on a rock.”

The people of South Uist – where she stayed for six years until she married, moving first to Barra and then settling in Canna – were equally amazed.

Fiona – who as Gaelic associate artist of National Theatre of Scotland produced a show about her muse titled Little Bird Blown Off Course, touring the Highlands and culminating in 2014 with a Celtic Connections performance in Glasgow – revealed: “The people of South Uist at the time were astounded that somebody would want to take down their songs and stories. But there was a mutual respect.

“They called her Miss Shaw and later Mrs Campbell. She respected them. She didn’t try to be ‘Lady Bountiful’. She lived and worked with them and she was the first person (from outside the islands) who had done that. She milked the cows, she fed the chickens, she lifted the seaweed; we have film of her with the seaweed trails on her back.

“She did everything because she recognised that the songs came from that labour and she really wanted to understand what drove these people to make these songs.

“There were people before her like Marjory Kennedy-Fraser who collected songs, but she turned them into art forms where they lost all their soul and became pieces of classical music.

“In terms of the pristine collection of that heritage, Margaret is unsurpassed. What makes her unique is that she lived with these people. She was respected and loved by them and is still loved and respected by them. Nobody since then has done that. She stayed for years and years and that is entirely, and completely unique.

“When you team the songs she collected with the photographs, and the voices of these people, their correspondence, and in some instances things like scarves and socks and artefacts that we have at Canna House you have a complete picture of a lifestyle that is gone.

“That picture helps us to understand today who we are as Scots and where we have come from, and the significance of that cannot be understated.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © Shutterstock / snapvision

© Shutterstock / snapvision