After cancelling last year, the biggest movie event in the world is back. The Cannes Film Festival is an almost mythic event in the film calendar.

Movie stars from around the world ascend its famous red-carpet steps to massive film screens where careers are made (and sometimes unmade).

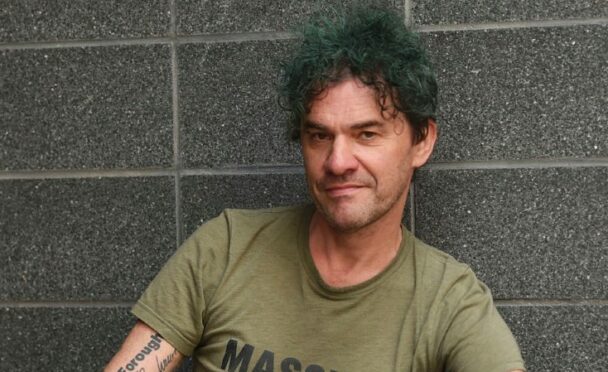

This year, two of the films in Cannes, including the movie that launches the 2021 edition, are directed by…me. It’s the first time a Scottish or British filmmaker has had two movies in the pantheon, so the pressure is on.

How did I – a working-class Irish lad who has lived in Scotland since 1983 – get to the top of those red steps? The answer tells us something about the movies themselves.

I was a nervy but passionate kid. My family had no connections in the world of the arts, theatre or cinema, but I went to the movies as much as I could, because it was affordable and, in its adventure and vast luminosity, sublime. It was, you could say, the people’s art.

But there was something else. Movies felt like my brain. As we all know, images and memories flicker in our heads. They arrive in our inner eye like shots, then are replaced like a movie cut. Films caught audiences’ imaginations around the world because they worked how our minds work.

In Scotland in the 1980s and 1990s the film industry wasn’t huge, but I noticed, in that time, the second thing about the film industry. Passion for film helps you succeed. Through my work at the Edinburgh International Film Festival, I got to know Sean Connery. He saw my passion and phoned people like Steven Spielberg to recommend me to them. In my own career I’ve similarly tried to keep an eye out for perhaps shy kids who really know and love movies.

Technology changed in those decades. Cameras and editing equipment became much smaller and cheaper, and gradually cinema opened up to more types of people. The result is that, now, many of the best films don’t come from the Hollywood studios. We see fables or incisive movies from all over Africa, from Thailand, Romania, the Philippines and wherever imaginative people are.

Like many of you, I regularly have to go into things that scare me (in my current situation, Cannes film fest next week).

My approach is to bring a book that's the OPPOSITE of that situation, that world.

If you're chemically minded, formula is

Acid+alkali = salt+water+CO2— mark cousins (@markcousinsfilm) July 2, 2021

Recently, of course, Covid forced us into our own homes and, also, into ourselves. And what did we find in there? Amongst other things – movies.

We rewatched our favourite classics, and streamed movies on Amazon Prime, Netflix and other platforms far more than previously.

Again, the affordable sublime helped us through the melancholic Covid hibernation. I know that, for me, cinema has always felt like such a reliable friend. It has taken me by the hand in periods of self-doubt, and opened my eyes.

In my life as a filmmaker, I’ve worked with Jane Fonda, Jack Lemmon, Tilda Swinton, Rod Steiger, Martin Scorsese, Lauren Bacall and many of the greats, and in each case I noticed something: they are known for their Oscars, their glamour, their famous lives, etc, but what they really want to talk about is film itself.

When it was invented in 1895, cinema entered our unconscious lives. It has remained there despite social, technical and public health challenges. Some nostalgic people say that its time in the sun is past, that we now only want to sit on our sofa and stream films. I don’t think so. My time in the sun in Cannes will, I hope, remind me again why I love the movies.

Mark Cousins’ films The Story of Film: A New Generation and The Storms of Jeremy Thomas are out later this year

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe