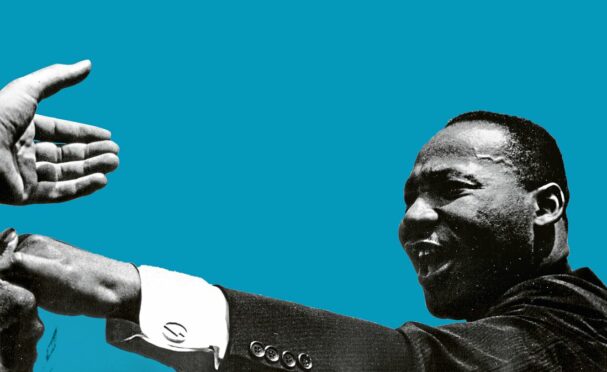

If the assassin’s bullet had missed that fateful day in Memphis, Tennessee, Martin Luther King might have been celebrating his 94th birthday today.

And, if his life had taken another twist, years before his assassination in Memphis on April 4, 1968, he may have been celebrating in Scotland, according to the author of the first new biography of the civil rights leader in more than 40 years.

Years before his calm and courage changed history as the 1960s flamed into riot and civil unrest, he had designs on a life in Scotland, a country he is said to have considered as “progressive” with egalitarian values chiming with his own.

The colossus of the civil rights movement, who would go on to lead the battle to end racial segregation and Black disenfranchisement in the American South, was only 39 when he died but just 21 and a recent graduate when he applied for doctorate study at Edinburgh University.

Accepting him, the university recognised King’s great promise and ability. For King, it was an important validation in a world where the colour of a person’s skin was still more important than the contents of their brain or soul.

However, while tempted, King, who was later awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, did not take up Edinburgh’s offer, honouring his father’s wishes that he remain in the US.

As America and the world prepare to honour tomorrow’s official Martin Luther King Jr Day, biographer Jonathan Eig, retired Church of Scotland minister Iain Whyte who met King in Atlanta, and Ian Houston, a lecturer in African American leaders in Scotland, revealed his affinity with the country he might have called home.

Speaking from Chicago, Eig – whose book, King, is based on hundreds of interviews with those who knew him – told The Sunday Post that King’s interest in Scotland was likely sparked by reports of other Black Americans who had flourished here.

He said: “There is no doubt that King would have been aware of the racial progressiveness he would find in Scotland and would have been aware of the contrast between Scotland and the United States at that time.

“A big part of why he and a lot of black men of his class were applying to Edinburgh University was that it offered them a chance to escape the very strict racial code in the States.

“I often think about how King’s life and how America would be different today if he had attended Edinburgh University because he might not have come back. He had a white girlfriend, Betty Moitz, and perhaps he would have felt if he moved to Scotland he could have married her.

“He might never have returned to the south and the civil rights movement. He expressed at that point in his life that he wanted to be an academic. He thought he would preach for a couple of years and then take a post teaching.

“He went to Boston University for his doctoral work, and he was still surrounded by a large community of black students. He learned about how racism in the north differed from racism in the south and that was an important part of his evolution.

“He made up his mind that he wanted to go back to the south. If he had studied in Edinburgh and didn’t have that same large support network of Black American people around who knows what his next step would have been?

“In Scotland maybe the passage to professorship and an academic career would have been smoother and he might not have emerged as a key activist of the 1960s in America. He might still be with us.

“But his father was not happy about him leaving for Europe. Going to Boston was bad enough but going so far away to Scotland really upset him.”

Dr Iain Whyte, a retired minister and racial justice campaigner based in North Queensferry, met King in Atlanta in 1964 and later took part in the Mississippi Summer Project – a drive to boost the number of registered Black voters. He said that while he spent only 30 minutes with King, it was immediately apparent that he cared deeply about opinions in Scotland.

He said: “I had just completed my first year at Trinity College, Glasgow and was spending a summer based in Columbia Seminary near Atlanta. I entered the South on a Greyhound Bus when King was in Washington observing President Lyndon Johnson sign the Civil Rights Bill, that first national legislation to extend human rights to African Americans.”

It took two months before he finally met with King. “I spent half an hour with him,” he remembered. “He shook hands with me and we talked. He was mainly interested in how the people in Scotland saw the struggle.”

Whyte said that as “a graduate of Morehouse College, the elite Black men’s college,” King would have known of historic Black figures James McCune Smith and Frederick Douglass. McCune Smith in 1837 became the first African American to hold a medical degree from Glasgow University, which now has the James McCune Smith Learning Hub. Frederick Douglass, a Black American leader and slavery abolitionist visited Scotland on a number of occasions in the 1850s and was, Whyte said, “very involved with the Glasgow Emancipation Society”.

“At the end of our time together King said: ‘Please go back to Scotland and tell them about our cause’. The other thing he asked was if I could find time to go to Montgomery in Alabama and see Clifford and Virginia Durr. Clifford was a lawyer and had taken up the cases in the Montgomery Bus Boycott [a mass protest that led to a 1956 Supreme Court decision that the town’s segregation laws on buses were unconstitutional]. Virginia was a social worker.

“King told me: ‘The whites despise them, and the negroes won’t go near them, they are too frightened to befriend them, so they depend on contact with people from outside.’ I visited them. It was a remarkable meeting.”

He later joined activists to “desegregate” a cinema in Mississippi: “We were surrounded by guns of the Mississippi State Patrol. It could have been very dodgy but there was some kind of compromise.”

And on his way back to Atlanta, a bus change found him in Meridian where three young activists were immediately before their disappearance and murder. Whyte said: “The friend who got me the job preaching in Alabama to finance my summer said I could have been feet up in the Mississippi. But I wanted to do it. I don’t regret it.”

In 2015 Whyte was the only Scot to join King veterans for the 50th Anniversary of the Montgomery to Selma marches that had protested the blocking of Black Americans’ right to vote, and was attended by America’s first black president, Barack Obama. Whyte said: “It was one of the great experiences of my life.”

Washington DC-based Ian Houston, honorary professor and lecturer at the University of the West of Scotland and Aberdeen University is also an ambassador for Black Professionals Scotland.

The expert on African American leaders in Scotland said: “One poignant part of the King story is that he spoke in 1967 at Newcastle University – where he received an honorary doctorate in Civil Law – only months before he was assassinated in April 1968. I have no doubt he was mindful of that acceptance letter all those years before.

“Edinburgh University wrote that his transcripts were of high quality, and offered him admission as a post-graduate student for 1951. King would have drawn confidence seeing that an ancient university of world renown had admitted him. It was a significant moment for him personally. He would have told his parents, family, friends, and faculty. Scotland and Edinburgh would have sparked many conversations.

“The admission of King was also a reflection of the progressive values of Scotland and Edinburgh University at that moment. They recognised a young man of great promise and saw him for the content of his character and ability. It was an admirable endorsement of King long before he became the legendary voice rightfully celebrated by the world today.

“It was a proud moment for King, but also a proud moment of inclusiveness for the university and Scotland.”

‘He fought for us and the belief he could make the world better’

Martin Luther King Jnr was the first modern private American citizen to be honoured with a federal holiday. But it took 15 years of campaigning and battling opponents, a public march, a petition by six million people and a hit song by Stevie Wonder Happy Birthday before it was achieved. President Ronald Reagan finally signed the King Holiday Bill into law on November 2, 1983, designating the third Monday in January MLK Day.

But biographer Jonathan Eig points out: “In creating the holiday we have whitewashed King’s story. We’ve forgotten how radical he was because we celebrate the holiday in a safe and limited way, the racial integration and love, without thinking about some of the more challenging things he said.

“He was really calling for America to remake not just its politics but its economy. He felt like American capitalism had not evolved in an equitable way. He was strongly anti-materialism and anti-military (opposing the Vietnam War).

“We also tend to forget how badly the American government treated him. He was imprisoned and the FBI set out to destroy him and undermine his ability to work as an activist. They accused him of communism, bugged his hotel rooms, and leaked stories of his sexual life to reporters to undermine his reputation. Now the American government, in celebrating him, is hoping that we forget that.

“King was a man, not a saint. He had flaws and we should acknowledge that. If we expect him to be perfect, we cannot even hope to live like he did. But if we see him as a human being who had aims and struggles, then his achievements are greater because he overcame all of that. He fought for us, and the belief that he could make the world a better place.

“So many of the things King talked about are still troubling us. I want people to feel, from the book, that he was a person they cared about and not just an institution, or monument or a national holiday. I want them to see how strongly he believed in God and how that compelled him to try to change the world; that he would risk his life for his beliefs.”

King: The Life Of Martin Luther King by Jonathan Eig, is available now to pre-order

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe