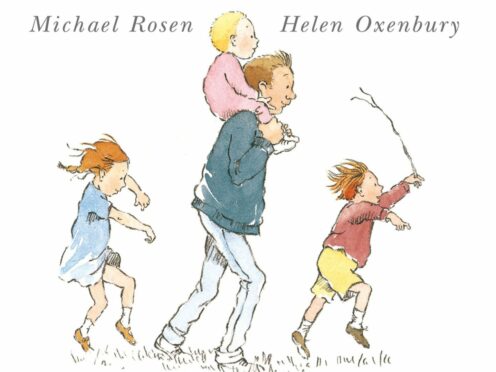

In Michael Rosen’s children’s classic, We’re Going On A Bear Hunt, a family go on an adventure to a dark cave before hastily retreating home having sought (and foolishly found) their ursine quarry.

Before each obstacle on their return journey, the children in the tale repeat a chant about not being scared. Rosen, 75, can’t quite say the same for his own difficult journey home.

He was, he admits, more fearful and somewhat less unscathed than his fictional creations by his battle against Covid last year when doctors gave him a 50% chance of surviving.

Although now contending with Long Covid and other health problems, the former children’s laureate believes the pandemic can have a happy ending; not just for him but for all of us.

This week the poet and author will appear virtually at Edinburgh’s Just Festival to talk not only about his brush with death but about how we have the potential to build a more equal society as a result of the pandemic.

“Covid is a serious illness and I would like people to know that it is,” says Rosen. “I’d like to put across what it means to face a serious illness but also what it means if you get the chance to recover, or at least start on the road of recovery.

“How much care and love do we need in order to do that? You can’t do it on your own. The NHS and my wife and family gave me that.

“Obviously the NHS is our birthright; to have them, my family and wife helping is a wonderful, special gift.”

This optimism and positivity has been hard-fought. In his book, Many Different Kinds Of Love, Rosen outlines how he came down with Covid and ended up in intensive care where he spent 47 days in an induced coma. It was a ward where, he later discovered, nearly half of his fellow patients died.

While the worst is behind him there are lingering effects of the disease that hamper the quality of his daily life.

“I just sort of see shapes and blurs now,” he explains. “My left ear doesn’t work very well.

“If I turn the hearing aid up the sound is very distorted but I can hear a bit three-dimensionally. I have numb toes. I have dizziness, and I sometimes get vertigo.”

The physical effects are taxing, he admits, but not as concerning as the “chasm” between his brain and his body. “I sometimes feel quite fragile and weak mentally,” he adds. “I feel exposed to something I didn’t fully understand. I lose my sense of humour very quickly, which is a shame.

“If there’s a little setback it becomes a major setback. Today I lost a book. I mean, who cares if I lost a book? I can say to myself, ‘how absurd’ but I got upset. It’s all part of the fragility I feel. And I do get angry about it all.”

This anger comes from a place of compassion and humanity; two qualities that in Rosen’s view too often seem lacking in public life.

“If you said to people in 2016 that 160,000 people would die and it wouldn’t be a matter of national mourning, people wouldn’t believe you,” he says.

“We mourn an aeroplane that falls out the sky, rightly so. We mourned a disaster like Aberfan, all those years ago, and this is what this pandemic is.

“One of Shakespeare’s lines was about how ‘like flies to wanton boys are we to the gods’. “It feels like we’re flies and the government sit smugly making jokes about it.”

The government’s handling of the pandemic is a source of Labour supporter Rosen’s ire. He worries the organisation that saved him could become Covid’s final, long-term casualty.

“We’re going to get a battle for the NHS,” he adds. “Over the past 18 months the NHS has shown what a beautiful and wonderful instrument it is for dealing with something like this, and for looking after us.

“A nurse said to me that the nation’s health is the nation’s wealth. Isn’t that wonderful? I love it.

“You have no economy if you don’t have the nation’s health. And so what the NHS has shown us, through its wonderful diversity and care at all levels, from the people cleaning the floors to surgeons doing incredible operations, is that it’s an incredible instrument to have thought up.”

It is testament to Rosen’s character that from dark times he can extract brightness. In the coming months and years, the author is asking people not to lose sight of the positive behaviour seen across society throughout the pandemic even when it wasn’t displayed by those running the country.

“When the pandemic arrived people saw it as an opportunity to make money,” he adds, speaking about the numerous expensive government contracts handed out over the past year.

“But there is always an opportunity for people to see other ways to do things. Look at what helped people. The vaccine. Social action. Helping each other.

“If people can get to see the world work that way, it’s something worth fighting for. We can build better.”

Reassessing our approach to education could be key to creating a better society, says Rosen, an Oxford graduate with a PHD in children’s literature.

One of the issues raised by last year’s lockdown was how children have missed vital education, but that is only if education is considered within the parameters it has traditionally been boxed in by – and maybe it is time that changed.

“Human brains don’t stand still,” he said.

“There’s an idea that’s sprung up in the past year that certain people who are disadvantaged by the pandemic are going backwards, or they’ll become cave dwellers because they don’t have the benefits of civilisation the rest of us got.

“It just may be that people are doing different things now.

“Obviously you can test people and say, ‘well they haven’t learned how to read or do their sums’ but you have to find out what else they’re doing.

“We have a deficit model with education, where it’s believed certain people are deficient because they don’t have the right teaching.

“We’re applying that model to children now and the only thing we can say is that there is more deficit. But maybe they’re doing other things away from education that isn’t measured purely by scores or grades.

“The measures for children we have in place are so narrow, they even leave out the arts and humanities now. We measure maths and science which are valuable but how do we measure compassion, cooperation, courage and creativity?

“What model of humanity do we want? What if people have been learning to care for each other over these past 18 months? We don’t know because we’ve not measured it, we don’t bother to try.

“The scores we keep aren’t the sum total of who we are as human beings. Always remember The Beatles were school failures.”

Michael Rosen will appear at Edinburgh’s Just Festival on Saturday

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © David Levene / Guardian / eyevine

© David Levene / Guardian / eyevine