Growing up in the foothills of the Himalayas, Merryn Glover has always felt the call of the mountains, but it wasn’t until she began exploring the trails and summits of a less imposing massif that her connection to nature deepened.

Since becoming writer-in-residence for the Cairngorms National Park four years ago, having moved to the area with her family in 2006, Glover has ventured further into the landscape’s waterways, forests, lochs and peaks.

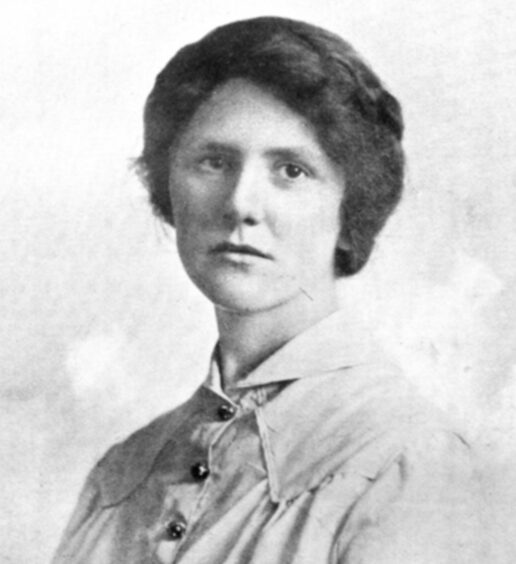

Throughout her journeys to better understand some of the highest mountains in the country, the writer found herself continually returning to the work of author Nan Shepherd, whose The Living Mountain is considered a masterpiece of nature writing.

Described as a “meditation on the magnificence of mountains”, Shepherd’s writing details her own walking throughout the Cairngorms, and is a deeply personal account of her love for the landscape.

For Glover, who was born in Kathmandu and has lived in Nepal, India, Pakistan and Australia, Shepherd became an “invisible friend, walking guide, writing tutor and fellow wonderer”, and in March 2020 she began work on her own contemporary response to The Living Mountain, following in her predecessor’s footsteps, but landing in new and unexpected places.

“I didn’t know quite where it would go, which in a sense is part of the spirit of her book – setting out on the journey not knowing the destination,” explained Glover of the writing process for The Hidden Fires.

“I knew what it could not be was an effort to copy her book, and it also was not going to be a straightforward guidebook as those things exist. So, I didn’t necessarily know quite what the book would become.

“That later emerged in my writing as I was reflecting on Shepherd, and as I was reflecting on what I was seeing and experiencing in the hills. It was very much a journey of discovery. What is it that I want to say here? What do I want to explore? What do I want to share, particularly when so much has been said about Shepherd herself, and so much has been said about the Cairngorms? What can I bring to this that might be new, that might be distinct?

“As Nan said, ‘The more I penetrate into the mountain’s life, the more I penetrate into my own’,” continued Glover, who has also written plays for radio, numerous short stories, and two novels.

“There is very much that sense of when we’re able to take time in nature, we discover what it means to be human. Our sense of our own naturalness – that we are nature too, we’re not an alien species or an invasive species, although sometimes we behave that way.

“We are a part of the total mountain. We are as intrinsic to it as the ptarmigan and the wild azalia. We belong here. It isn’t like we are making some kind of foray from the other world where we really belong and then we take this little expedition into nature and then retreat back to urban habitations. It’s more about going home.

“When I go out into the natural world, out to the landscape, and really breathe, really feel it and sense it, I realise this is where I belong. I’m a part of this, too.”

Although now considered a literary and ecological pioneer, and even immortalised on the Royal Bank of Scotland £5 note, Shepherd did not experience widespread acclaim during her lifetime.

She wrote and published three novels, but after only one unsuccessful attempt to have The Living Mountain reviewed by a publisher, she put the manuscript away in a drawer, where it stayed complete but untouched for more than 30 years. It was finally published in 1977, when Shepherd was 84, but like the work itself, the route to publication was unconventional.

During her journeys into the mountains, Glover, who believes Shepherd’s modest nature would make her “uncomfortable” with the degree of attention she has attracted in recent years, often wondered about her decision to keep the book to herself.

She said: “She was pragmatic and realistic about the realities of the industry. It took a while for her early novels to get published, and a lot of that was down to her friend, Agnes Mure Mackenzie, peddling these books around to different publishers and persuading them to take them on. So she was very aware of the fact that you couldn’t just write something good and somehow expect it would be discovered and acclaimed.

“Although it is quite intriguing why, with The Living Mountain, she really only made one effort to get it published after it was written. When she finally brought it out, I get the sense that she just couldn’t be bothered faffing around anymore with trailing around publishers and so on – she just felt it needed to be the out there, so she self-published it.

“She paid for her own print run of 3,000 copies through Aberdeen University Press. They obviously recognised its value, but she had to pay for that, and all distribution and marketing was down to her – which is probably why it didn’t go very far.

“There were some early reviews, but she gave away lots of copies and most of them were still sitting there when she died. It is intriguing as to what made her think, ‘Actually I will put this up there.’

“But it’s valid and it’s important, and it’s just wonderful that she did eventually publish.”

Since publication, The Living Mountain has inspired a legion of writers, hillwalkers and nature-enthusiasts, just like Glover, who says Shepherd’s enduring appeal is being an environmentalist before her time.

“She had a profound ecological sensibility,” mum-of-two Glover added. “She has a passionate love and care for the environment, and she’s very aware of a lot of the issues that are quite current today around things like deer numbers on sporting estates, and the economics of grouse moors and the effect that has on the local population of the landscape.

“She references those things, but she also acknowledges that there are people for whom that is necessary labour. She said, ‘These things don’t change on the turn of the wrist’.

“It’s complicated and that’s one of the things that is appealing about reading her work – she allows people space to reflect on the issues and to find their own place within that rather than being dictated to in terms of what it means to be feminist, an environmentalist, a mountaineer or any of those things.

“She doesn’t do that and I think that’s part of her enduring appeal.”

The Hidden Fires, Polygon, is published on Thursday

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM