A mass campaign against a lethal disease passing unseen through the air, petty national rivalries, and a world-first breakthrough. It might sound familiar…even 60 years on.

Then, Scotland was the only country in Europe, apart from Portugal, to experience a rise in tuberculosis (TB) after the Second World War. For decades, Britain had resisted taking up two life-saving measures – the BCG vaccine and pasteurisation of milk, partly at least because both had originated in France.

Young women were at particular risk and half of those diagnosed would be dead within five years.

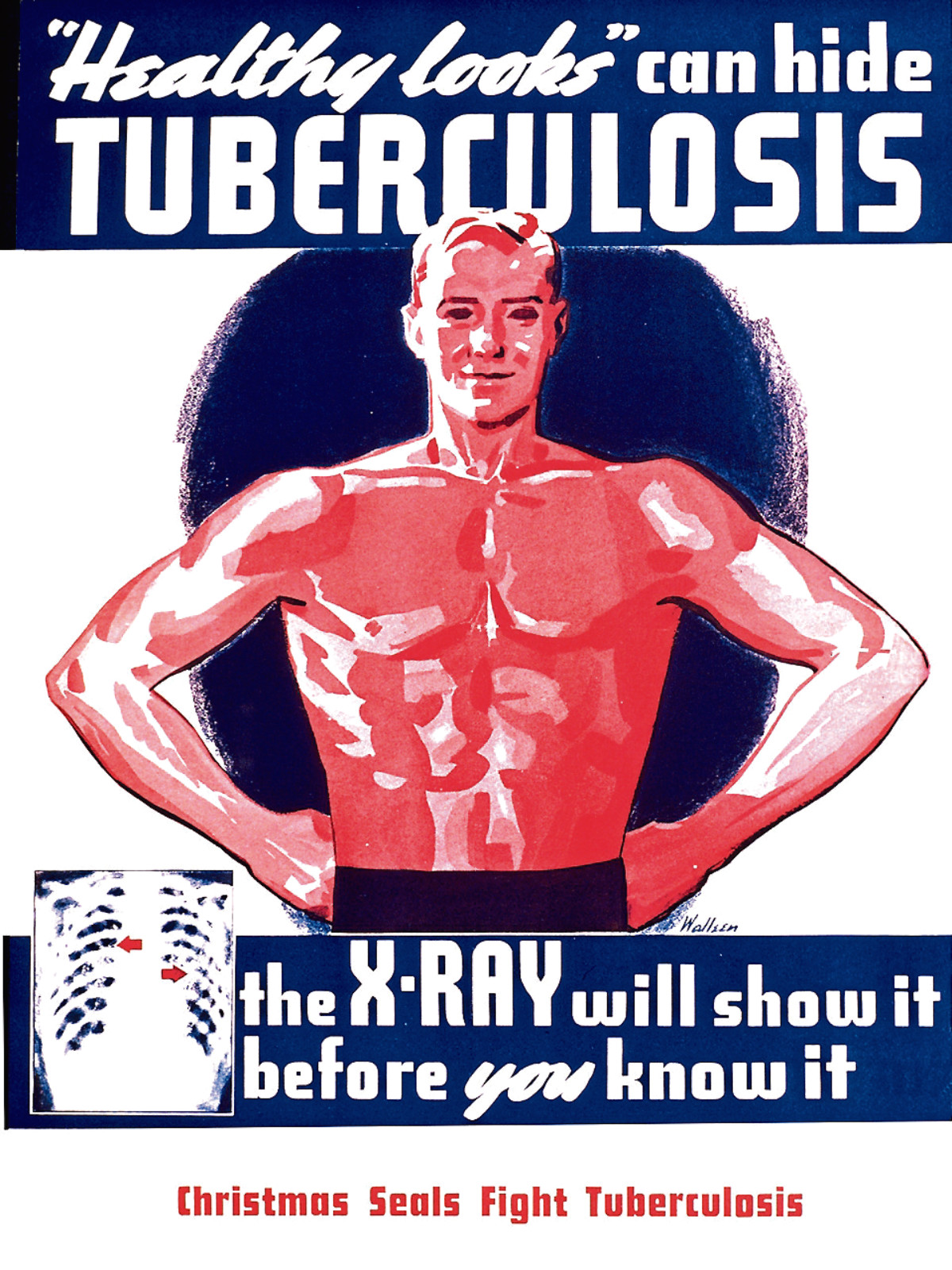

There had already been publicity campaigns – against the stigma surrounding TB and against spitting, which spread it. New drugs offered better hope of cure and more than 1,000 Scots children had been flown to sanitoriums in Switzerland for treatment.

But the disease would never be eliminated until remaining cases were identified in the wider community. So mass X-ray campaigns were rolled out across the UK – based on successful efforts in American cities.

Glasgow, with the highest TB rates in Britain, was the first, and 35 mobile units were drafted in from across the UK in an intensive five-week campaign in 1957.

It was a huge organisational challenge undertaken by Glasgow Corporation (local authorities then had the lead role in public health), the health board and the Department of Health. In the end more than 700,000 adults were X-rayed – nearly three times the original target.

Glasgow provided useful lessons for the Aberdeen campaign and for Edinburgh in March 1958. Publicity helped, with posters, adverts, news coverage and films featuring entertainers such as Stanley Baxter and Jimmy Logan.

But Glasgow showed this wasn’t nearly enough. It enlisted thousands of volunteers to spread the word in the tenements and housing schemes – chapping on doors to reassure, persuade and cajole folk in their own homes, reminding them of the benefits in taking part.

A bit of bribery helped, too. Prizes were offered for those who took part. Edinburgh pulled out all the stops with a house (valued at £3,000 then), and a new car as top prizes. Others had more modest offerings – in Greenock it was £50, or a season ticket at Cappielow. All of this was organised by a publicity committee. In Edinburgh’s case this had the editors of seven national newspapers, plus executives at the BBC, Scottish Independent Television, and cinema owners.

The media weren’t touchline spectators – they were tasked with reaching “the lazy, the selfish and the disinterested who would not come from motives of civic or family responsibility”. A survey showed reluctance among older people, so the committee added another prize for the over-60s – a pension of £2 a week for life.

Billy Smart’s Circus provided huge tents in Princes Street Gardens and the castle was lit up with an enormous sign.

Newspapers carried daily totals of activity to encourage competition between council wards. Churches rallied support and shops gave display space. In all, 7,500 volunteers were recruited for home visits. Older school children delivered letters from the Medical Officer of Health.

It was the last great demonstration of the wartime spirit of solidarity and everyone pulling together for the common good.

So, did it work? More than 300,000 people braved the snow and ice to come out and get screened – some 84% of the adult population. Everyone got a badge. It also revealed several hundred undiagnosed cancer and heart disease cases.

TB patients were also benefiting from a revolutionary cure pioneered by a team led by respiratory disease expert Sir John Crofton. Rising TB notifications in Edinburgh were halved between 1954 and 1957, a feat not achieved anywhere before or since.

Many people were cured with one or two of the drugs, but thousands also developed drug resistance, relapsed, and died. Crofton’s group used all three drugs from the outset and scrupulously monitored each patient’s progress with bacteriological tests.

The tests also showed whether the patient had stopped taking the most unpleasant drug, PAS, something nurses knew about from finding the powder stashed away in the ward piano or secretly chucked out of the window.

The Edinburgh treatment became the gold standard thanks to a trial in leading TB hospitals by the Paris-based International Union Against Tuberculosis. Waiting lists disappeared. It gave the NHS its biggest beds boost because sanatoria were no longer needed.

Crofton’s team moved into other areas of medicine because they had effectively made themselves redundant. Among them was Jimmy Williamson, medical adviser for the X-ray campaign. He later recalled his last TB patient: “He was a nice chap who had a shadow on his lung. I told him it was tuberculosis – and he grabbed my hand and said, ‘Thank God!’

“If I had said that to him 10 years earlier, he would have wept. The difference was that he knew he would now be cured – and he was.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © ITV/Shutterstock

© ITV/Shutterstock © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM