It has been hailed a timeless classic of Scotland’s wilderness. One woman’s meditation on a mountain that captures the whole world, charting our relationship with the environment.

The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd details her awe and enduring passion for the Cairngorms and has inspired countless writers, walkers and wanderers, yet the masterpiece of nature writing almost didn’t see the light of day.

Shepherd, who previously wrote and published three novels, left the manuscript complete but untouched for more than 30 years before it was finally published, which Erlend Coulston, a long-term friend, and now literary executor of her estate, attributes to the writing being ahead of its time.

“When she wrote the book, she only advanced the idea once to a publisher and then put it away in a drawer,” explained Coulston, whose mother struck up a friendship as a child with Shepherd that lasted all their lives. “It does beg the question; why did she give up after only one tentative attempt? For her novels, she submitted the manuscripts to 12 or 13 publishers before she found somebody who would take them.”

Written in the 1940s and published in 1977, and often described as a “meditation on the magnificence of mountains”, there is a spiritual nature to The Living Mountain, with Shepherd herself likening her expeditions into the hills to a Buddhist’s pilgrimage.

Coulston continued: “I think she decided to give up so quickly as there was a huge cultural schizophrenia that had developed at the end of the 19th Century into the 20th, between people who viewed going into the hills as sort of aesthetic, almost a poetic experience, and those for whom it was a kind of manifestation of modernity.

“The later were equipping themselves with all the gadgets – compasses, telescopes, crampons and ice axes. Nan had a much more mystic approach, so she thought she was fighting a lost cause. There was no market for her style of writing, and she just put the thing away. I think that’s as good an explanation as any for her modesty, shall we say.”

The Cairngorm water is all clear. Flowing from granite, with no peat to darken it, it has never the golden amber, the ‘horse-back brown’ so often praised in Highland burns. When it has any colour at all, it is green, as in the Quoich near its linn. It is a green like the green of winter skies, but lucent, clear like aquamarines, without the vivid brilliance of glacier water. Sometimes the Quoich waterfalls have violet playing through the green, and the pouring water spouts and bubbles in a violet froth.

– From The Living Mountain by Nan Shepherd

Although the recognition may have only come towards the end of her life, come it did, and Shepherd is now considered a literary and ecological pioneer with her idea of our interconnection to nature very much of our times.

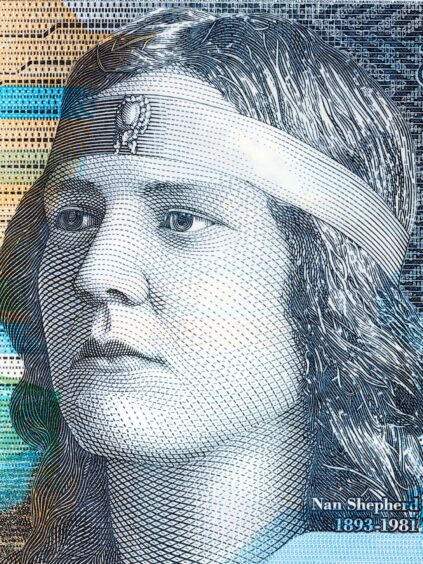

Today, Coulston explained, Shepherd’s work has inspired everything from nature writers and gin distillers to fashion designers and musicians, not to mention her inclusion on the Royal Bank of Scotland £5 note in 2016.

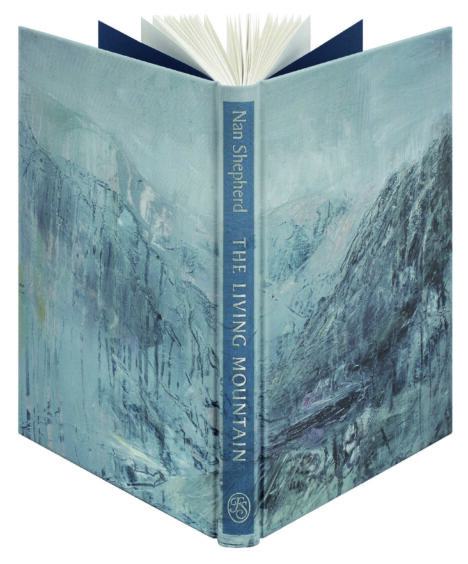

The latest incarnation of her work is a special edition of The Living Mountain, published by The Folio Society, and illustrated by artist Rose Strang, to celebrate Shepherd’s timeless ode to nature.

A fan of her “careful and beautiful writing”, when asked to bring Shepherd’s words to life, Strang started by following in her footsteps. She explained: “I climbed Càrn Bàn Mòr so I could have that freshness of experience to feed into the process. But, actually, when I came back to the studio, it was Nan’s words and her prose that came to mind.

“Nan herself is like an artist. The prose is so vivid and I used that as a starting point. One part that inspired me was when she describes falling asleep in the mountains, which includes the line, ‘But did I dream that roe?’

“I think that phrase says a lot about her response to the mountain and her wonderment – it’s a spiritual response, although she’s very grounded. That spoke to me because that’s how I feel about landscape, and it’s probably why I paint them.”

Shepherd dedicated much of her life to exploring and documenting the natural world, the depth and quality of which Coulston says was influenced by a desire to preserve her experience for future generations.

He explained: “There weren’t many women writers, and very few who had the nerve and inclination to devote their spare time to tramping about the hills.

“The quality of her writing is remarkable. You can trace it back to John Ruskin, as Nan, like most middle-class Victorians, had his books.

“He was obsessive about recording nature accurately, and said, ‘Hundreds of people can talk for one who can think, but thousands can think for one who can see’. In other words, he believed the ability to see is an extraordinary gift – and I think those words were something Nan took to heart.

“The images she snatches from the Cairngorms are extraordinary, and as true today as when written.”

Cameron McNeish, outdoors writer, author and columnist for The Scots Magazine, agrees that Shepherd had a natural ability to capture the atmosphere of the Cairngorms although the mountains she knew have changed with time.

He said: “She describes the Cairngorms really beautifully, at a time when they weren’t busy. When Nan wandered the Cairngorms and got her material for writing her book, the mountains weren’t nearly as accessible as they are now. For example, the road that now runs half way up the mountain once stopped at Coylumbridge. From there, it was only a track. On the other side, at Braemar, it would have been much the same.

“Quite often hillwalkers talk of ‘the long walk in’ and that was a very much a reality in the days of Nan Shepherd. It would have been a very remote, isolated landscape, much more so than it is today.”

The description of the isolation of the Cairngorms, Strang says, gives an insight into the chaos of the world surrounding Shepherd.

“There’s an urgency about her work. Other people writing at the same time were Tolkien and CS Lewis. Perhaps it was the proximity of war, and the thought of all that can be lost, that makes her writing so intense.”

Another fan is Elise Wortley, who after reading The Living Mountain for the first time, knew she wanted to experience the Cairngorms as Shepherd did in the 1940s, right down to her clothes and shoes.

She said: “She was one of the first people to write about why it’s not just about getting to the summit of the mountain but climbing is so much more.”

For Coulston, seeing his friend’s talent and passion now acknowledged by so many is a delight. He said: “Her posthumous celebrity only really took off about five or six years ago, and since then has been extraordinary saga. The writer part of her, I think, would be gratified that, at last, she is being recognised, too.”

Merryn Glover: Walking these hills like she did, we come to love them like she did

Merryn Glover is writer in residence for the Cairngorms National Park.

“The perfect hill companion is the one whose identity is, for the time being, merged in that of the mountains, as you feel your own to be.”

So wrote Nan Shepherd in The Living Mountain nearly 75 years ago. I think she would be pleased to know it is exactly what she has become for me over the past 18 months as I have tracked her routes across the Cairngorms.

I am writing The Hidden Fires, a response to her book and her relationship with this remarkable range, the granite heart of Scotland. She grew up in Aberdeenshire, walking from childhood across the Deeside and Monadhliath hills, and into the Cairngorms first as a young woman, continuing until age prevented her. Once over her initial urge to speed to the summits, she increasingly took time in ever-slower exploration of all the facets of the range, delighting as much in tiny ice formations as the spectacular views.

Foremost for her was to discover the “essential nature” of the mountain, tuning the inner self to be one with the outer world. Such a long, deep acquaintance meant she came to know this landscape intimately, from the rock beneath her, to the weather-tossed skies above, to the living creatures and plants in between. Far from breeding contempt, such familiarity fostered wonder.

“However often I walk on them, these hills hold astonishment for me,” she said. I echo that, being fortunate enough to live right at their hem. My journey to the Cairngorms, however, could not have been more different.

I grew up in Australia and south Asia, much of it in the Himalayas, and only began to discover Scotland’s hills when moving here in my mid-twenties. Those early experiences were marked by rain, mist and cold and it has taken me time to acclimatise. Much of that adaptation has unfolded in the Cairngorms and I have come to recognise the beauty and distinctiveness of these mountains.

Through Shepherd, I keep rediscovering them in fresh ways, particularly by following her example of enjoying the natural world like a child. Rather than being driven to arrive or complete or win, we can meander, pause, investigate, contemplate and even snooze.

We can take the “unpath” or take our kit off for a spontaneous dip or take ages watching an insect. Most importantly, we can go out “merely to be with the mountain as one visits a friend with no intention but to be with him”. Like Shepherd, in this place of generous and open presence, I have found love.

The Folio Society edition of Nan Shepherd’s The Living Mountain, illustrated by Rose Strang is available exclusively from www.foliosociety.com

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe