While Glasgow was quick to reap the benefits of the slave trade, it has taken a much longer time for the city to get over what has been described as a “collective amnesia” when it comes to its involvement.

But more efforts are being made to acknowledge the city’s past and how it prospered during the times of colonialism, especially following the events of 2020.

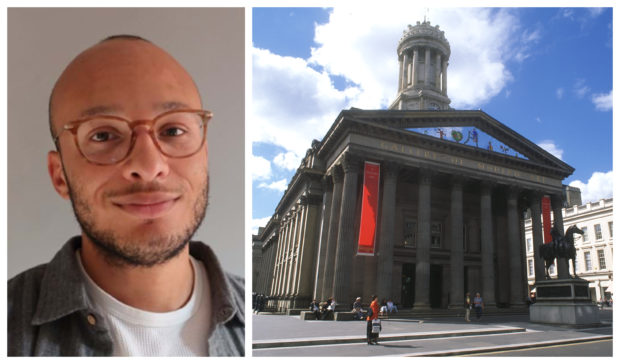

Earlier this year, Glasgow Life appointed its first curator to look specifically at the legacies of slavery and the British Empire.

Miles Greenwood’s remit will be to ensure the city’s museums continue to tell the story of the impact, which is still seen today reflected in society’s inequalities.

“Museums are a very important part of a wider process,” he explained. “I think Scotland as a nation, the UK and all countries that have ties with colonialism have to look at how they can address these histories and legacies broadly, but museums obviously have to do more than that.

“In many ways, they’re key in making historical research accessible to the public, who they serve. I think that’s an important part for us, the process is all about working with people outwith the museum, with communities, to look at how best to bring out these stories.”

Working with local communities and existing specialist curators, Miles will put together a public programme that will include talks, tours and exhibitions.

He hopes to utilise Glasgow’s vast collections, alongside lived experiences and stories gathered through consultation work, to create an overall strategy for how the museum service addresses the legacies of colonialism and slavery going forward.

Discussions with the public will be a cornerstone for this work, reflecting the fact this history cannot be neatly packed into one single, all-encompassing experience or story.

“Glasgow has such an obvious connection to empire, and I think it’s important that we listen to people,” Miles said. “I think that’s key to the success of any project like this.

“Consultation is one way, actually asking people how they think we should be approaching it, but it’s also important to look at ways of incorporating the voices of people, particularly those whose heritage is most closely associated with this history.

“We want to be looking at ways we can explore it, interpreting and telling their version of the history in their own terms.”

Miles, whose grandparents came to the UK from Jamaica as part of the Windrush Generation, said that interpretations and experiences will vary depending on factors like class, gender, age and ethnicity.

“I have my own interpretation of the histories, but it’s not just my story to tell and it’s not just the museum’s story to tell. I’m not an expert on everyone’s experiences, I can only speak to my own, my family’s and what I’ve learned so far in my life.

“Colonialism has shaped our society as we know it, which means that so many different people have different perspectives and views on it.”

How society untangles itself from prevailing attitudes and conventions around race dating back centuries has become an even more prominent issue this year.

The killing of George Floyd by police in Minneapolis in May saw a surge in support for movements like Black Lives Matter, which had already been in motion for several years.

From footballers taking the knee before matches to worldwide protests and the toppling of statues, the subject of race has become more of an everyday topic of discussion.

With calls too for more education on Black history in school curriculums in Scotland, the appointment of someone in Miles’ role in the city’s cultural institutions comes at an important moment.

Through his work with the museums, he aims to not just tell the stories of the time, but also give people a wider understanding of how the Empire’s legacy still impacts people in their daily lives today.

He said: “What 2020 has done has made a lot more people aware, who weren’t previously, of how entrenched racism is in our society. I think people are beginning to have a real desire to understand how history has played a part in that. We certainly have a role to make those connections.”

Recent years have seen wider acknowledgement of Glasgow’s role as a former second city of the empire, through books like Stephen Mullen’s It Wisnae Us: The Truth About Glasgow And Slavery and several exhibitions and walking tours exploring how the area benefitted from the slave trade.

And Glasgow Life, who manage the city’s collections and museums like Kelvingrove and Riverside, have committed to telling these stories, and reflecting on their own part.

“In a way, it’s almost impossible to separate what we know as a museum from the Empire, it involves so much of our collection, from natural to social history, to what we call world cultures which in itself is a colonial idea,” Miles explained.

“The British Empire is completely embedded in the institution. Slavery is a bit more complex, we certainly don’t have as many objects as we’d like to have that tell the story of slavery. We do certainly have some though that we could look to use to interpret and tell those stories and make those connections.”

A brick-and-mortar example is the Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA) in the city’s Royal Exchange Square, which is housed inside a former tobacco merchant’s mansion.

There, a permanent display on the building’s balconies, named Stones Steeped in History, tells the story of its original owner, William Cunninghame of Laishaw, who made his fortune from trading American tobacco and Caribbean sugar with the use of slave labour on plantations.

“There are still ways we can do more at GoMA,” Miles said. “It’s a museum of modern art, and it does a lot to display work from artists of colour and that should definitely still be continued and be part of it.

“A lot of these people are descendants and have close connections to the Empire so I think displaying work by these artists is part of that work.”

As well as sharing stories and perspectives previously untold, something that all museums worldwide have to acknowledge, is how the colonial artefacts they display were originally acquired.

Most will have been obtained through purchases or agreements with original owners, but many in collections worldwide were simply taken under the empire.

“It’s becoming such an important part of museum work,” Miles said. “Of course, not all museum objects are taken under violence but those that are I think we have to have an honest discussion with the people who are involved about what the best thing to do is.

“If those communities want them back, and we are certain that they have been taken by any form of colonial violence then I think that’s something we should explore.”

The new curator post is funded for two years by Museums Galleries Scotland.

Miles takes on the role having graduated in Ancient Histories with a Masters in Heritage Studies from Newcastle University, and he has previously worked at Paisley Museum, where he developed a Black History tour of the collection which explored the town’s links with the slave trade.

His appointment came just before Black History Month, celebrated in October, but the aim is for Glasgow’s cultural institutions to tell the story of the roots of global inequalities all year round, and for generations to come.

He added: “Anyone who works in interpreting these histories always says that it’s Black History Month every month of the year.

“It’s important for us to look at how we can embed the histories into our programme and displays wherever relevant and important to do so.

“For me this is like a dream job, and it’s obviously very important and timely- or maybe slightly overdue. It’s still quite early days at the moment, but I’m looking forward to cracking on.”

Visit glasgowmuseumsslavery.co.uk for more information

The exhibits

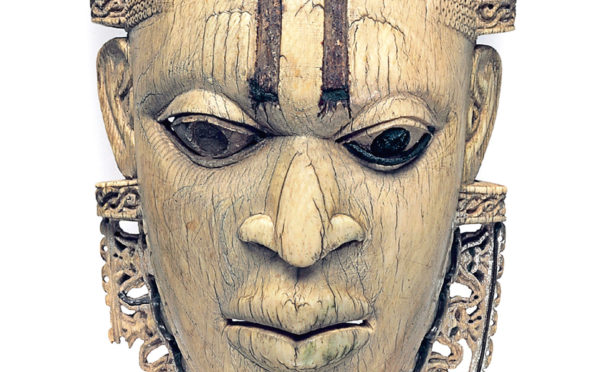

Here, Miles picks out two pieces from the Glasgow collection with particular relevance to the legacy of the slave trade.

Orisha figurine of Osain, purchased by Glasgow Museums in 2002 after an exhibition by a Cuban artist, Filiberto Mora

Figurines of deities from the Santeria religion are among Miles’ favourite collection of objects in the museums’ possession.

The religion, practiced across the Americas, has roots in the Yoruba culture of what is now modern-day Nigeria.

And its spread, Miles said, is an example of why the legacy of colonialism shouldn’t just be stories of oppression.

“It shows enslaved African people fought hard to retain their cultures, religions and identities despite the colonists and those trying to eradicate them,” he explained.

“Even those that were forced to cross the Atlantic and undergo brutal forced labour still maintained connections to their roots.

“The religion adapted and changed as a result of their new environment and the people they came into contact with. It’s quite intermixed with Catholicism now.”

Miles believes enslavement’s influence on culture is as much a part of the story as the “sheer brutality” of the system.

He added: “When we think of the cultural heritage of slavery often what people think of is things like shackles.

“While obviously an important part, there’s a whole wealth of other culture and heritage that had come about as a result of it. That’s something I’m interested to explore.

“It’s incredibly complicated, the Caribbean in particular is completely shaped by the period of slavery but also the cultural interactions of the people who were there before and those who came after.

“It’s made the Caribbean and much of the Americas what they are today.”

Glasgow Excursion Steamers and American Ship on the Clyde

An object in the museum’s collection with particular relevance to Glasgow is a stunning painting of ships on the Clyde in 1832 by Robert Salmon.

After further research into it, the American ship on the left was found to most likely be the Lindsays, arriving from New Orleans.

It was thought to have carried a cargo of cotton to a number of Glasgow merchants. The cotton would have been the product of the plantations of Southern America, and the importers would almost certainly be making vast profits on the back of slave labour.

“It’s such an incredible painting in itself, and visually striking,” Miles said. “What I found quite interesting about it was that it’s really depicting Glasgow almost on the cusp of becoming such an international centre for global trade.

“The symbols of it are all there, to the left of the painting you can see a sailing ship with the American flag, which would likely be carrying cotton from a plantation worked on by enslaved people.

“On the right, we’ve got a sailing ship with a German flag which is likely picking up the produce of some of that work or from elsewhere in the Empire. These are the things that enriched Glasgow.

“While it’s not a historic document, there’s such a clear symbol of how Glasgow came to be the city that we see now.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Supplied

© Supplied © Glasgow Museums

© Glasgow Museums

© Supplied by Glasgow Museums

© Supplied by Glasgow Museums © Glasgow Museums

© Glasgow Museums © Glasgow Museums

© Glasgow Museums