IT is the love affair across a social divide that has enthralled a nation for more than 100 years.

And now we can reveal what Queen Victoria really thought about her “heart’s best treasure” – the intense friendship she shared with Scottish ghillie John Brown.

It was a relationship that earned Her Majesty the nickname Mrs Brown – and was captured on-screen in the Oscar-nominated film of the same name, starring Dame Judi Dench and Billy Connolly.

Victoria’s candid and startling view of her manservant is drawn from her own diary and papers and forms the basis of a new book about her relationship with Brown.

In language straight out of a Mills & Boon romantic novel the swooning Empress of India tells how the towering kilted gamekeeper swept her off her feet and carried her across a Highland glen in his “strong and powerful arms”.

However, the author of Victoria – The Queen, expert Julia Baird, faced a huge fight to tell the story.

She was only granted access to the royal papers that form its basis after the intervention of a former governor-general, Quentin Bryce, and fought censorship to publish her account.

Brown, who was seven years younger than the Queen, went to work at Balmoral aged 21 when Prince Albert first leased the castle in 1848.

The young Queen had been fond of the “invaluable Highland servant”, who accompanied the royal party on climbing tours.

But their relationship changed shortly after the death of the Prince Consort at the age of 42 in 1861.

One diary entry – from October 7, 1863 – tells how Victoria had spent the day riding with her second and third daughters, Princesses Alice and Helena, stopping for tea before turning back home.

However, in “dark light” the Queen lost control and crashed to the ground.

Victoria wrote in her diary afterward that she had just a moment to think “whether we should be killed or not” but decided “there were still things I had not settled and wanted to”.

Victoria spent the next few days “helpless” in bed with raw meat on her black eye, nursing a sore neck and a sprained thumb that would remain crooked forever. It was pivotal moment as she rediscovered a zest for life – and the company of John Brown.

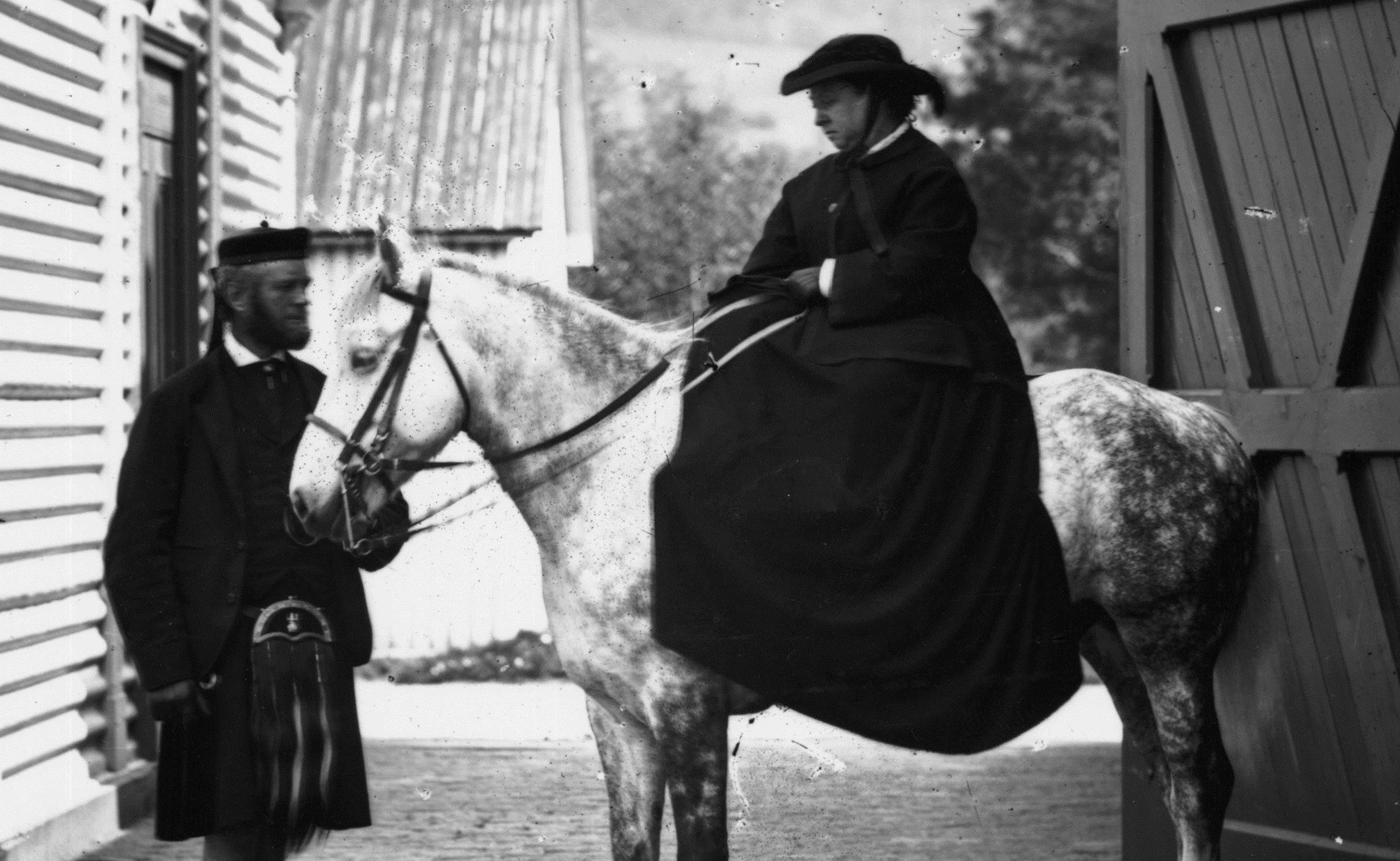

Her doctor ordered Victoria to continue to ride, and in the Highlands she grew accustomed to Brown leading her.

“A stranger would make me nervous,” she wrote. “I am now weak and nervous, and very dependent on those I am accustomed to and in whom I have confidence.”

By the following February the tall, handsome and protective Brown had the permanent title of the Queen’s Highland Servant.

By November, he was designated John Brown, Esquire. Victoria was charmed by his loyalty.

“He is so devoted to me – so simple, so intelligent, so unlike an ordinary servant, and so cheerful and attentive.”

As their relationship deepened – he was the only one who treated her as a woman, not a sovereign – she confided to her diary: “My dear pony went beautifully, like a cat and the way Brown carried me over and along the stones admirable.”

She described him as “so thoughtful and full of initiative, making an admirable guide and servant”. She added: “Brown with his strong, powerful arm, helped me along wonderfully.”

The next day Victoria recorded a jolly tour near Balmoral with Brown.

“One had heather up to one’s knees, holes, slippery ground and stones three feet high to get over. I tried my best, but could never have got on without Brown’s help.

“The going down was a wonderful but very amusing affair. It is quite a perpendicular descent and so slippery, that Brown, in trying to keep me up, came down his whole length.”

She added: “The descent was far easier, but the path was very rough in parts and I had recourse to Brown’s strong arm to steady me.”

Victoria doubled Brown’s salary, gave him a house for his retirement at Balmoral, and decorated him with awards.

She ordered the Balmoral property manager to trace Brown’s family tree and was thrilled when he linked him to Scotland’s most prestigious clans.

Brown’s final service to his Queen was to be the death of him. In March 1883, worried by an unsolved attack on 26-year-old Lady Florence Dixie in Windsor, the Queen asked Brown to investigate.

Her faithful servant combed the area for hours in the wintry air, looking for answers. He then spent a week carrying around the Queen, whose knee was swollen from a sprain.

All the while, Brown was battling a severe cold. The next weekend, Brown came down with erysipelas, a painful syndrome wherein the entire face swells, including ears and eyelids. Two days later, at the age of 56, he was dead.

Victoria, who spent 18 years in the company of John Brown, almost as long as she spent with her beloved Albert, was inconsolable with grief.

After Brown’s death, Victoria copied out an extract from a diary or journal entry from 1866, and this was found among his brother Hugh Brown’s things when he died.

“Often my beloved John would say, ‘You haven’t a more devoted servant than Brown’ – and oh! How I felt that!

“Often I told him no one loved him more than I did or had a better friend than me: and he answered ‘Nor you –than me. No one loves you more’.”

Her book More Leaves from the Journal of Our Life in the Highlands, published in 1884, was dedicated to Brown, and she continued to mourn him until her own death in 1901, erecting a full-size bronze statute at Balmoral.

She was also buried with a gold wedding ring that had belonged to Brown’s mother, which she had worn constantly since his death.

There was also a coloured photograph of John Brown in profile, in a leather case with some locks of his hair, and other photographs of him, which she carried in her pocket, placed in her hand.

And finally “a pocket handkerchief of Brown, whom she praised for his faithfulness and singular devotion, to be placed not near but on her”.

Victoria – The Queen, by Julia Baird, is published by Little, Brown.

READ MORE

10 facts from the Victorian era that prove people weren’t quite as buttoned-up as we thought!

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe