Neil McLennan began his career as a history teacher, but has been involved in all sectors of Scottish education, working with young offenders and as a development officer both nationally, with Learning and Teaching Scotland, and at local authority level.

A senior lecturer and a director of leadership programmes at Aberdeen University, he is a member of the Scottish Futures Forum, a Holyrood thinktank tasked with creating a vision for education in 2030.

When Covid struck, education took an early hit. At the beginning of lockdown, schools closed and learning moved online as teachers were forced to innovate and children to become more independent. Neil McLennan says the sudden shift only exposed existing flaws.

The attention on children’s mental health highlighted what charities have been saying for years: that there was too much focus on attainment, not enough on well-being. Meanwhile, the grading system used in place of cancelled National 5s and Highers discriminated against pupils from deprived areas, demonstrating that inequality was not inadvertent, but built into the system.

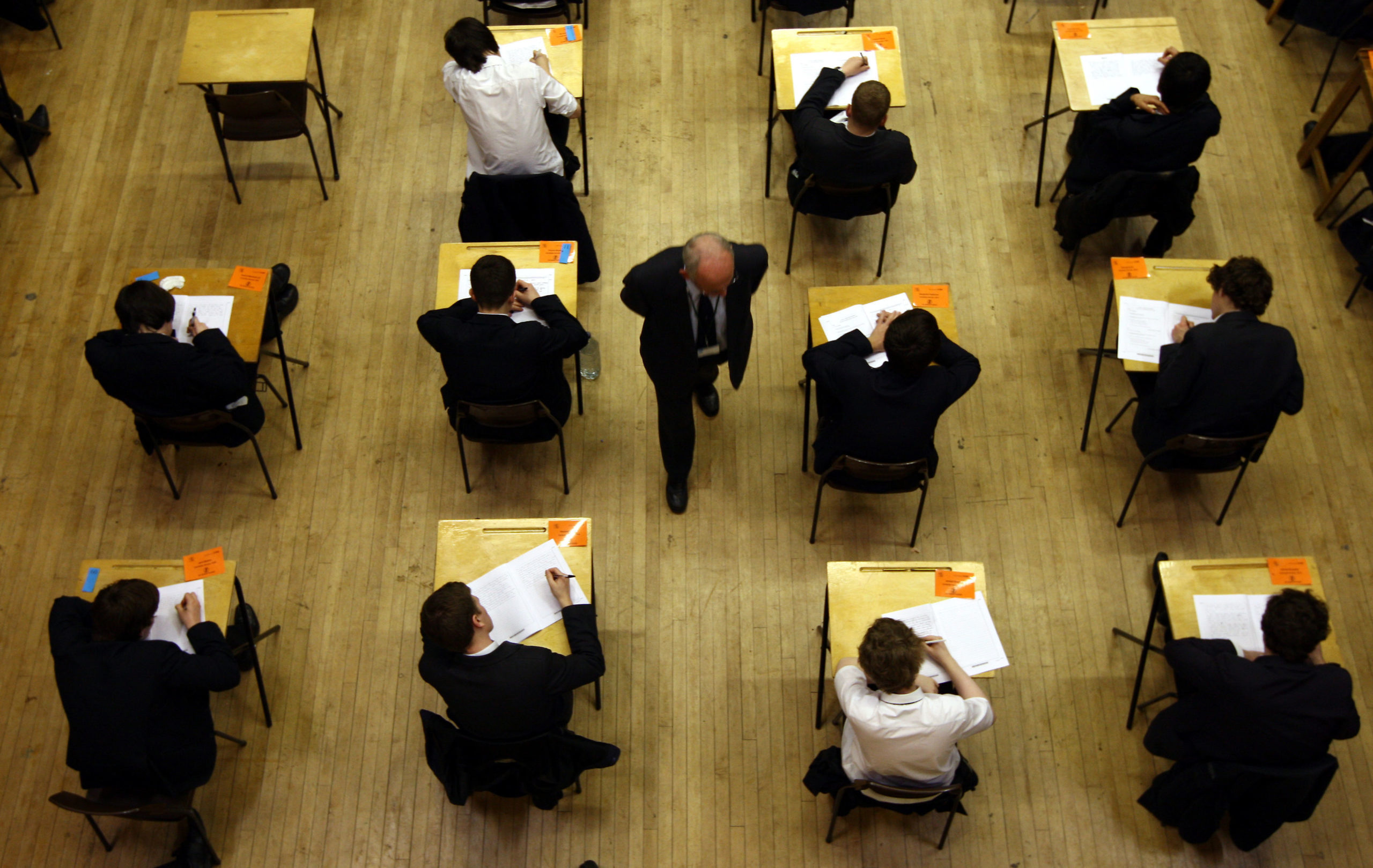

Confronting such truths is depressing, but it also affords an opportunity: to reflect on what education is for and come up with a radical new approach; to jettison our existing industrial model, where children sit in classrooms being spoon-fed information, in favour of something more flexible and suited to the 21st Century.

One of the first things McLennan would do is to dismantle the Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) and Education Scotland – organisations he sees as lumbering behemoths standing in the way of change.

“At the moment we have centralisation and a cosy consensus between those who have control in education and that is not always delivering the best outcomes for our young people,” he says.

“The rhetoric we hear is one of empowerment but the reality is we are subject to more control than ever before.”

McLennan says the problems at Education Scotland were obvious in its failure to produce online teaching resources during the pandemic. He wants to see it split into an independent inspectorate and a support wing run by teachers, for teachers – an organisation more akin to the former Learning and Teaching Scotland, which focused on the method of teaching and drove innovation.

As for the SQA, he supports its abolition. “It’s been in the spotlight for many years with an apparent inability to reform,” he says. “I think there’s a chance to change that and break the monopoly it holds over examinations.” McLennan points out that, while other countries have qualification authorities and inspectorates, many of them also have NGOs and charities and business start-ups supporting education.

“Of course, the challenge with moving towards a free-market model here is that Scotland is a small country, but the ideas are out there. We have great practitioners throughout all of our schools, yet their ideas are often suffocated by the bureaucracy of these macro-organisations,” he says.

If schools are to gain more autonomy, McLennan believes the culture change needs to extend to councils. “Local authorities are a useful arbiter of resources, ensuring manpower or money is distributed equitably, but they can also complicate things,” he says. “There are some things that are sent out nationally to the 32 local authorities, where they go into what I call the ‘tumble drier’. They birl around for a few loads and all that happens is they come out delayed and hotter than they were when they went in.”

There are those in Scottish education circles who believe last year’s SQA results fiasco should serve as a catalyst for scrapping exams altogether. McLennan does not believe this is feasible or desirable but he does want to see both a wider range of potential qualifications, and a better balance struck between exams and ongoing internal assessments.

Ending the SQA’s monopoly would open up the market, allowing pupils to sit, among other things, A Levels and the International Baccalaureate (a worldwide nonprofit education programme) as some private school pupils already do.

“Everything is benchmarked against the Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework, so there’s no reason you couldn’t have young people doing a blend of different qualifications if they felt the teaching was better, the currency was useful in an international market and, most importantly, the service they were getting from the exam provider was superior.”

Alongside exams, which are arbiters of knowledge, he says there ought to be a better method of assessing those skills such as the ability to present, discuss, negotiate and listen.

McLennan describes a system of assessment used in Denmark. “Pupils are set a task. They are given time to go off and do that task, then they come back and present to a panel which includes their teacher,” he says. “They present on the task itself, but also on their learning during the process. Those on the panel have a set of criteria – they tick off the ones that have been met and grade the pupils accordingly.

“In exams, teachers are marking papers of kids they have never met, but in the Danish model they have the children in front of them: they can ask them questions and find out more about their understanding.”

Perhaps the biggest change Covid has wrought on the education system has been the increase in the use of technology. Early on, some teachers tried to recreate live lessons, but this was mostly abandoned in favour of exercises that could be accessed in the pupils’ own time.

While home-learning has had its stresses, and some digital inequities will need addressed, McLennan says it has had positives too. It has forced a shift away from the “empty vessel” style of schooling – where teachers input knowledge for pupils to regurgitate, to one in which pupils go out and discover things for themselves.

“The number one education provider in Scotland just now is not teachers or schools – it is Google,” he says. “Information is easily accessible – what we need to be doing in an age of fake news is to help young people to discriminate between good sources and bad.” McLennan says technology could also be used to allow pupils to study a wider range of subjects.

“Technology could allow pupils to access different subjects online at their own convenience and work through lessons at their own pace, coming together with learning mentors at particular checkpoints during the day,” McLennan says.

“It would allow pupils to study subjects which might have clashed on a traditional timetable and even to dip in and out of taster courses.” McLennan believes that, since the schools closed, many older pupils have been getting up later and working later into the evening as suits their body clock. “The school day is based on the needs of the economy as opposed to what is in the best interests of young people,” he says.

“There are two options here: one is to delay the start of the school day and see if that makes an impact, the other is again to use technology to allow pupils to learn at the time it suits them.”

He is also calling for a change in the school year. He wants exams pushed back to June/early July so they align with England’s, and the long summer holiday scrapped. The logic for pushing back exams is that it would give pupils longer to cover the courses and the logic for getting rid of the long summer holiday is that doing so might narrow the educational attainment gap.

“The current school year, with its long summer holiday, was introduced when we were an agricultural country and children were needed to help on the farm, but it has never served the needs of the less well-off,” McLennan says. “Those young people who have access to trips to castles, sports camps foreign holidays thrive, but that’s not the same for every kid – for some there will be a big drop-off in knowledge.”

For several years now, charities have been warning of a mental health crisis in our young people, but it took Covid to really focus people’s attention and spark a reflection on what it is we really want from education.

“There are four main purposes of schooling,” says McLennan. “The first is to give young people knowledge and the second is skills development. The third is difficult to define, but it’s about knowing oneself and encapsulates issues of mental and physical well-being. And the last one is about citizenship and community cohesion: how does an individual connect with other people round about them?

“What we see in education is a focus on exams and a little bit on skills with the other two happening largely by accident. In the initial stage of Covid, mental health moved from being the third purpose of education to becoming the primary purpose. What we need to ensure coming out of the crisis is that the four purposes are viewed as equally important.”

McLennan points out that – unlike numeracy and literacy – there is currently no attempt to measure outcomes on well-being. “We don’t want outcomes suddenly foisted on schools,” he says. “So, sooner rather than later, we should open up a national conversation on what success in mental health and community cohesion would look like.”

McLennan warns there are potential pitfalls as we move beyond Covid. “In an era of isolatory politics, we need to guard against any notion of education as a source of nation-building and to reassert the need to develop global citizens,” he says. “One thing that will help us this year is that the UN Convention of the Rights of the Child is being incorporated into domestic law. Article 29 states that you have a right to education that develops your personality, your respect for others and the environment.

“That’s a game changer because it means it’s not just about your own narrow view of the world it’s about other people’s views as well – and on top of that you get that sustainability and environmental agenda in as an actual aim.”

So, will something better emerge from the embers of the pandemic? McLennan says in its early stages Covid drove educational change at a rate that would have been unthinkable before; the key is to ensure that momentum is sustained. “Trotsky said: ‘War is the locomotive of history’. We know that crisis generates change. There is an opportunity here to transform education. We mustn’t squander it.”

The big ideas

Neil McLennan on how Scots schools can change to improve children’s education.

DISMANTLE BUREAUCRACY

At the moment we have centralisation and a cosy consensus between those who have control in education, and that is not always delivering the best outcomes for our young people. The rhetoric we hear is one of empowerment but the reality is we are subject to more control.

TRANSFORM EXAMS

There’s no reason you couldn’t have young people doing a blend of different qualifications if they felt the teaching was better, the currency was useful in an international market and, most importantly, the service they were getting from the exam provider was superior.

TEACH TECHNOLOGY

The number one education provider in Scotland just now is not teachers or schools, it is Google. Information is easily accessible – what we need to be doing in an age of fake news is to help young people to discriminate between good sources and bad; to understand what they are being fed.

HARNESS TECHNOLOGY

Technology could allow pupils to access different subjects online at their own convenience and work through lessons at their own pace, coming together with learning mentors at particular checkpoints during the day.

CHANGE THE DAY

There are two options here: one is to delay the start of the school day and see if that makes an impact, the other is again to use technology to allow pupils to learn at the time it suits them.

CHANGE THE YEAR

The current school year, with its long summer holiday, was introduced when we were an agricultural country and children were needed to help on the farm, but it has never served the needs of the less well-off.

SEIZE THE DAY

Trotsky said: “War is the locomotive of history.” We know that crisis generates change. There is an opportunity here to transform education. We mustn’t squander it.

NEXT WEEK: Claire Mitchell QC on The New Normal in Scotland’s courts

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © David Jones/PA Wire

© David Jones/PA Wire

© PA

© PA