“Are you Banksy?”

The man in the queue has come from Huddersfield in search of the elusive artist, or his work at least.

“Nah,” says his wife. “You’re too young.”

Sherrie Davies-Mosley is here with husband Kenny to visit student son Kalum. And Banksy.

They’re eating chips and mushy peas and have maybe had one or two. Kenny says Banksy is the only artist that would draw him to a gallery in a city hundreds of miles from home in the middle of the night. They’d been to a talk about Banksy while on a P&O cruise.

I tell them I might be Banksy. You just never know.

Banksy in the dark

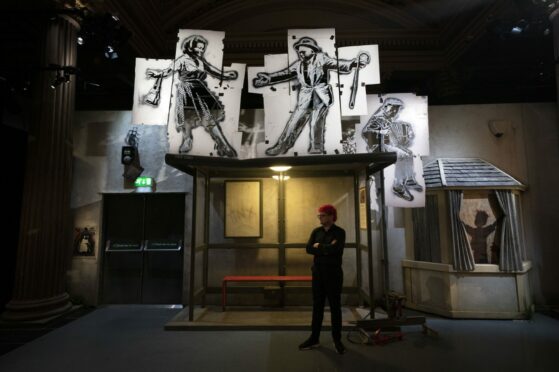

Since Glasgow woke up last week to find it had been decorated by the enigmatic street artist – not just the usual one overnight stencil, but an entire take-over of the city’s prized Gallery of Modern Art – tickets have been as elusive as the artist him (or her) self.

Except, that is, for those keen to enjoy their art under the cover of darkness. Just like the spray-painting pimpernel does.

At 1am, GoMA – normally a daytime hang-out for skater kids and goths, and a night time hang-out for pubgoers covered in kebab sauce and women carrying their shoes – was oddly quiet. Security guards and stewards patrolled the entrance to the gallery with clip-boards and headsets, in case anyone got rowdy at the prospect of seeing stencil art.

Tentatively, I approach a woman sheltering by one of GoMA’s neoclassical columns. I ask her if she’s here for the Banksy exhibition.

“The Banksy expedition? Hic. Naw. Ah’m waiting furrabus. Ah wishaWIZ going on a Banksy expedition but. Hic.”

A drunken philosopher stops to share an insight. “What’s the difference between ignorance and indifference?” he asks. “Don’t know. Don’t care.”

The night stretched on ahead.

The visitors

A man dressed in a unicorn onesie with a rainbow chain-link harness and a USB cable wrapped around his neck approaches me. I wonder if he’s an actual Banksy come to life.

He tells me his name is “Eejit AKA Unicorn” or Mike Cormac. He’s a DJ and designs emojis, among other things.

He’s driven from Edinburgh in a soft-top, arriving two hours early for his 3.45am slot in a sudden violent downpour. “I wanted to be the first of the last,” he says. “When I heard that it was open almost 24 hours, I decided to come at the time that makes the least sense to see who else was coming at that time. I’ve come early to experience the cultural magnificent that is Glasgow.”

Eejit tells me that Banksy communicates things that are often overlooked or discussed in heated ways in a playful manner that allows them larger levels of exposure, and makes difficult subject matters more accessible.

I’d had Robert De Niro’s “all the animals come out at night” line in my head from Taxi Driver all day, thinking about what it might be like here tonight. So far the only animal is a rainbow-coloured unicorn.

Glasgow architecture student Jack Lawlor didn’t even mean to be here at all. “I thought I’d booked tickets for 2pm but they turned out to be 2am,” he says. “Thought I was booking myself a lie-in. Little did I know.”

His pal Seumas Beathan asks me if I have a ticket he can buy. I tell him I’m only working, and have no skin in the Banksy black market. He tells me he hoped he might be able to jump the barrier, “like you can at the Queen Street station toilets.” Maybe not with Donald Trump’s security team on the door, mind.

As the hours pass, I begin to realise that Banksy’s anarchistic art draws a crowd of quietly respectful pilgrims in the wee hours between Friday night and Saturday morning.

Mother and daughter Sarah and Carol Tranent show me their Polaroids of posing in the artists’ phone box and bus shelter. Stef Stankiewicz leaves without getting his and tries to get back in again. Father and son Charlie and Lloyd Rohan say that they started a rumour in the queue that Banksy was posing as a journalist outside.

And true to form, by the time anyone looked, he was nowhere to be seen…

Walls have fears: Don’t be scared of graffiti street culture, says artist

It has become the hottest ticket in town, a curated street-art exhibition in Glasgow’s flagship modern art gallery.

Yet just a few yards away from Banksy’s high-profile show in GoMA, the city’s amateur street painters run the risk of being fined for working on urban walls.

The appearance of Banksy’s first solo exhibition in 14 years has led to accusations of hypocrisy from some in the city’s street art community.

Painter Conzo Throb says the absence of legal painting walls for graffiti artists in Glasgow points to a failure in the local government’s creative foresight.

He said: “There’s a major hypocrisy. It’s a lack of belief in Glasgow’s culture. There have been people getting fines for painting down in the Clydeside walk, and being told to stop.

“But that area is crying out to be made into a legal wall.

“Yet the council see having Banksy here as asset, he’s worth something to them, he prints gold. I was a huge fan of Banksy as a kid, and I wouldn’t have got into street art if it wasn’t for him, which is the same for a lot of artists now, even though some wouldn’t admit to it.

“It’s the same in other areas. When he does something in a city, councils come and put perspex over it to protect it, whereas other stuff that’s good gets buffed off.”

Throb, who works in partnership with fellow artist Ciaran Globel, has contributed urban public art across Scotland and and internationally.

He said: “It brings vibrancy to a city. Seeing a changing wall is great. It brings photographers, videographers. When this stuff happens, culture tends to follow.

“There’s no promotion or help given to working-class graffiti artists. They don’t know how galleries work. I’ve been doing this for years and I don’t either.

“So the council can change the rules, as Bansky was working-class and now he’s a multi-million pound asset. People don’t always appreciate you can create assets for the future by funding them now. It helps promote the country, its culture. But the vision to plant that seed has been neglected.

“It’s something that needs to be talked about for the Glasgow scene, or you’ll keep getting a lower bar of graffiti street art. It would raise the culture.”

Fellow city street artist Panda has also challenged Glasgow City Council to create a legal painting wall, calling for a proportion of amount spent on removing graffiti art to be diverted into the support and development of street art and graffiti. His Colour Ways initiative supports artists working in the urban genre, and he cites London’s Leake Street as a successful example of a legal graffiti wall.

Artist Rogue One, one of Glasgow’s most prolific public realm artists, agrees that a wall sanctioned by local government would help others hone their skills. He said: “It’s good for graffiti art and street art people to have a place where they can spend the day painting and enjoying themselves, not just run up to a wall and try to do something in 20 minutes.

“These walls push and drive these graffiti artists to get better, and that can lead on to commissioned work.”

Yet he also sounded a note of caution.

“They’ve had legal walls before, bit it can lead to vandalism – the young ones don’t get to paint on the wall, because they’re for the cool kids. So it can lead to tagging in surrounding areas, turning them into hotspots for graffiti, and that can ruin things.

“It also gets political. Talk of legal walls is often just councillors trying to make themselves look good, when they know full well they’ll be taken away again.”

Glasgow City Council have confirmed the possibility of a legal wall in the city is being considered.

A council spokesperson said: “We are considering how to best strike a balance between removing graffiti while also supporting street art and that includes the consideration of a legal graffiti wall. As part of those wider discussions, we are looking to bring a paper on the graffiti wall before councillors in the autumn.”

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Jane Barlow / PA

© Jane Barlow / PA © Jane Barlow / PA

© Jane Barlow / PA © Jamie Williamson

© Jamie Williamson © Jamie Williamson

© Jamie Williamson © Jamie Williamson

© Jamie Williamson © Heather Fowlie

© Heather Fowlie