The first clue came in a phone call. While her father was in hospital, Fiona Barrett overheard her mum Joyce telling her aunt Lena that the kids should visit him before his condition worsened.

But which kids did she mean? Fiona and sister Beverley knew their dad had Alzheimer’s and living with him they’d seen he was deteriorating before their eyes – so it couldn’t be them.

Taken aback but unwilling to question it directly, his death set in motion a search for answers that would span the next couple of decades and would eventually reveal that Samuel Brunton wasn’t just Fiona and Beverley’s father, but a dad to six more children.

And everyone knew the secret, except them and their half-siblings.

“It was like a brick wall of silence came up with all the family,” Fiona recalled. “No one would talk to us. No one would tell us anything.

“There was clearly something going on, so it was a matter of digging. We hired a genealogist and she did remarkable work but we came to a standstill until the web came along and all these records suddenly became available that we could access without having to try to ask a member of the family.

“It was like finding the very foundations of what my life and my siblings’ lives have been built on were actually completely unstable and the house could come down at anytime.”

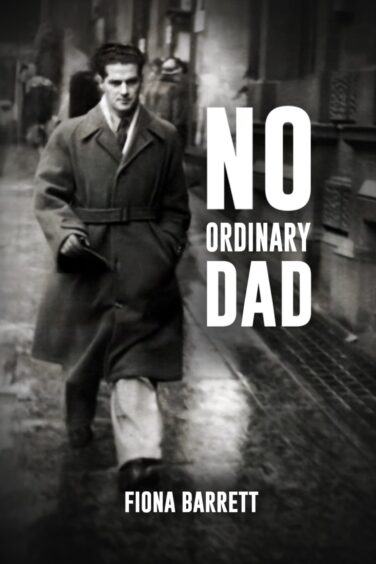

Mum-of-four Fiona charts the journey in new book, No Ordinary Dad, which goes back generations to tell a – mostly – complete family story.

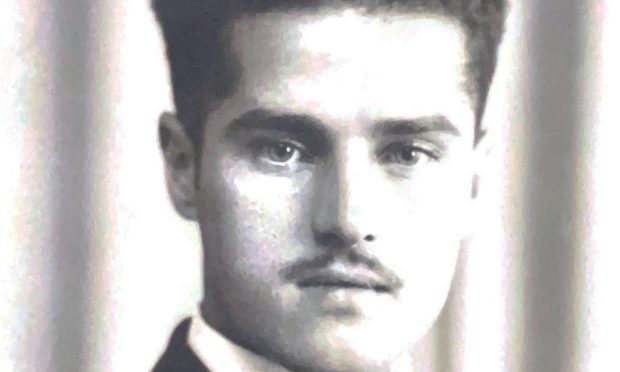

Even without the revelations, her father lived an extraordinary life. Born in Canada, Samuel came to Glasgow in 1919 aged four with mother Josephine, originally from Ayrshire, and baby brother Jack.

He grew up in Scotland and attended Glasgow University before joining the Army, with records suggesting he was part of the International Brigade battalion fighting in the Spanish Civil War at the 1937 Battle of Teruel.

He then worked in the John Brown shipyard in Clydebank as an apprentice electrical welder. Despite his position as a key worker for the war efforts and his membership of the Communist Party, he eventually joined the parachute regiment.

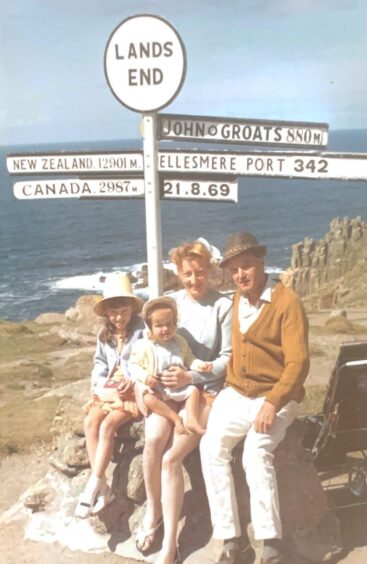

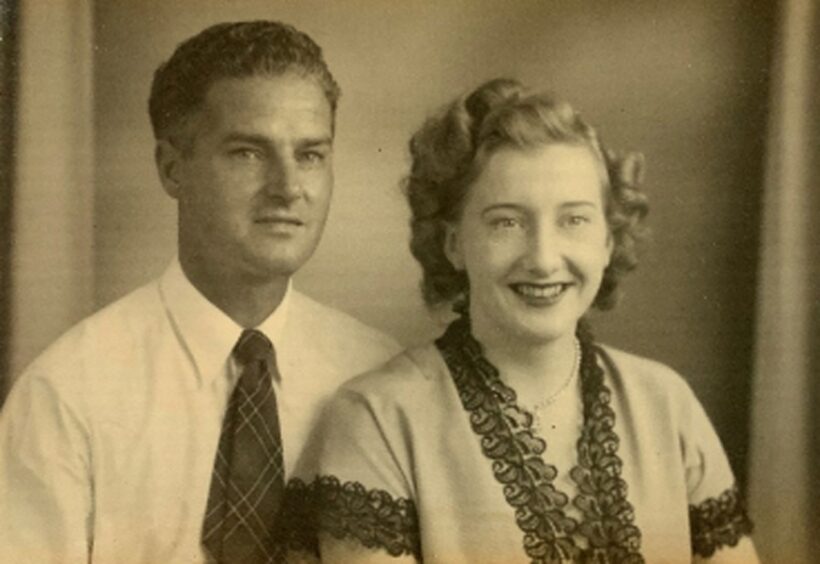

He was discharged in 1947 and moved south three years later spending the latter part of his career as a safety inspector. In Ellesmere Port, Cheshire, he met Joyce Swinburn and became father to Fiona and Beverley, sending postal cheques back to Scotland for the upkeep of his other family.

He died in 1990, aged 74.

Fiona trawled through photographs, documents and various archives to piece together parts of the puzzle while Beverley searched online to add branches to the family tree.

Samuel and Joyce married in 1977, but his name also appeared on a Catherine Shevlin’s death certificate as her spouse when she died in an Airdrie care home in 2001.

The sisters found their father had married her in 1938 and had six children. Left behind in Baillieston when he moved south were sons David, Edward, Peter and Samuel and daughters Josephine and Ellen.

After writing to anyone who might possibly fit the bill, and many rejections later, a revelatory phone call came as Ellen reached out one day while Fiona was out shopping.

Perched on a display bed in Homebase, for three hours she reconnected with a newly-found half-sister. Fiona and Beverley would go on to meet most of their new-found family.

“They could’ve said ‘your mum took our dad away, we don’t want anything to do with you.’ But it’s not been like that at all,” Fiona said. “They’ve been incredible, warm and welcoming and haven’t borne any grudges. It’s weird seeing your mannerisms and similarities in other people you’ve never met. Sam and Peter looked so like my dad. It was like seeing him alive again.

“Dad obviously thought he’d taken the secret to the grave. Mum would’ve very much liked to have been able to.

“These days no one would bat an eyelid about it. She just didn’t like being confronted with any questions. I think she always saw herself as the marriage wrecker, the vilified other woman.”

Fiona says writing about her family history and turning what started as shoeboxes of documents and photographs under the bed into a book has been very cathartic.

“I knew I might find information I didn’t like,” she admits. “I’d very possibly end up getting rejected, causing hurt to others and, at the end, I might have negative feelings towards my parents.

“To some extent that happened, but I’m old enough to process it.

“It’s like he was two different dads. I grew up with a very loving, gregarious, generous father and it’s very difficult to reconcile that with the one who walked out on six children.”

Some of the puzzle remains unsolved, like why Samuel left his family behind in Scotland.

“If I could wave a magic wand, go back and have a grown-up conversation with my dad, I’d have so many questions.

“He was extraordinary and I do wonder what he’d think about the fact Bev and I found his children. I think he’d be pleased.

“It was heartbreaking meeting Ellen, who died in 2014, for the first time. [Geographically] we were so close to her – [as a family] we used to go to see Lena and holiday in Scotland.

“We were choked up when she asked: ‘was that my dad coming to look for me?’ She was in her 70s but still had that little girl in her that wanted to know her dad hadn’t forgotten about her.”

One of the biggest struggles in writing the book was plucking up the courage to tell her mother about it.

However, at the end of 2023, Joyce passed away aged 90.

“It was almost serendipitous that she died just before it came out,” Fiona said. “I didn’t have to tell her. She’d have preferred it that way.

“She’d have been upset, but she always had the choice to be open and honest with me and chose not to. She had chosen her truth, I am choosing this, something I needed to do for me.

“I loved her to bits. I didn’t want to bring shame to her, and I didn’t want to embarrass her. But the desire to get the story out was stronger. Whether that’s right or wrong, I don’t know. In the end, the decision was taken from me – almost like she knew.”

Similar to genealogy shows like Who Do You Think You Are?, where famous faces have discovered previously unknown truths about their ancestors, Fiona hopes the book provokes conversations she was never able to have with her parents.

“We all deserve to know where we came from,” she said. “It gives you a sense of self, of where you’ve come from. We all kind of need that. Although our foundations were rocked, they stabilised once the facts came in and we were able to cement them down again.

“I’ve left a legacy for my children, giving them an idea of who their grandfather was. We gave peace to Dad’s first six children. They could see the whole picture. I’ve gained more family, which is never a bad thing. There are a couple of loose threads. In these scenarios there always are. There’s always one piece missing in the puzzle, isn’t there?”

No Ordinary Dad by Fiona Barrett is available on Amazon

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe © Supplied by Fiona Barrett

© Supplied by Fiona Barrett

© Supplied by Fiona Barrett

© Supplied by Fiona Barrett © Supplied by Fiona Barrett

© Supplied by Fiona Barrett