Nestled away on the Rosneath peninsula overlooking Loch Long, the Linn Botanic Garden became an extraordinary partnership of man and nature.

From 1971 until his death in 2019, botanist Jim Taggart made his home there, making use of its subtropical microclimate to cultivate exotic gardens of endangered plants from around the world.

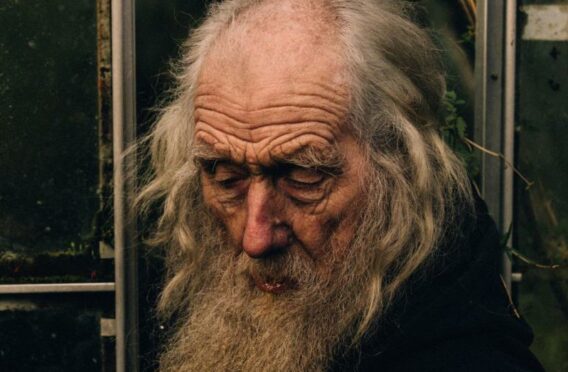

His final years were captured by acclaimed photographer Robbie Lawrence, who is putting the images on display as part of his first ever institutional exhibition.

Over four years and throughout the seasons, Lawrence visited the garden, which is now being restored under new ownership, describing each image as “a portrait of Jim”.

He said: “The story is effectively about Jim and his development of that garden, and the loss of his son who he had trained to be a botanist.

“He would travel around the world and bring back plants to grow there. When he got too old to travel, his son Jamie took over.

“I found it a very enchanting, magical place and he was an incredibly intriguing character. Every time I came back to Scotland, I’d visit him, and so the book spanned years, until Jim died.

“Despite his age, Jim would bound around the garden, occasionally stopping to provide a lengthy anecdote about a particular fern or tree.”

Taggart studied botany in Glasgow before reading theology and philosophy at Oxford. In 1971, he bought the Linn villa and used his collection of exotic plants to transform the gardens.

Son Jamie took over in 1999, but on a trip to find new species for the gardens in 2013 he disappeared in the mountains of Vietnam.

“Five or six years later it transpired that he’d fallen,” Lawrence said. “Jim kept the garden going as a sort of memorial to his son.

“He lived for the garden, it energised him. When he was in it he was far more lively and lucid than when he was inside. It was therapeutic.”

On Lawrence’s last trip, which hadn’t been planned in advance as Taggart did not have a mobile phone, something felt different and the garden was overgrown.

He would find out that Taggart had died, and the project had now become a moving record of his final years.

Lawrence believes that photographers carry a great deal of responsibility when picking up their camera to communicate stories like that of Taggart’s as honestly as they can.

But he also recognises that there will always be a certain element of subjectivity when approaching a topic or person.

“You’ve got to be very conscious of your own perspective or stance, and my work is, in some instances, seen as quite romantic by some.

“I’m aware that I have the capacity to potentially romanticise or idealise a certain topic. I think certainly in regards to things like Linn, that character of Jim becomes almost mythical.

“It’s not an overly conscious act, but it’s something that I’m aware of. So I think even though I knew him relatively well, there’s a lot also to be interpreted in those images.

“I think what’s interesting, when people respond to the work, is that he almost seems like a vector for people’s own experiences with grandparents or parents or having lost children. So I think there’s something kind of interesting, at least in that ambiguity.”

Lawrence, who recently photographed James McAvoy and Benedict Cumberbatch for the New York Times, has spent much of his career away from his native Edinburgh.

His exhibition Northern Diary, opening in Edinburgh next month, brings together a selection of work from the past seven years, including landscapes, portraits and still lives taken across Scotland’s cities, rural locations and coastal towns.

Included are photographs from his ongoing project documenting Scotland’s future post-Brexit, a film on Scottish country dancing, Blue Bonnets, and his project based on Taggart’s life and work, A Voice Above The Linn.

Based in London, he has taken on projects across the world in Congo, the Faroe Islands, Sierra Leone, the US and more.

“I haven’t lived in Scotland since I was 18, so I suppose my photographic relationship to it has always been one of return and sort of viewing the country as a proud Scot, but also as an outsider,” he said.

“Northern Diary kind of encapsulates that feeling of travelling north, which I find is always quite a romantic feeling in my mind.

“I quite like the idea of it feeling like a diary of sorts. As you wander through the exhibition it should feel like a series of recollections as much as anything.”

Robbie Lawrence: Northern Diary At Stills, Centre for Photography, Edinburgh from April, robbie-lawrence.com

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe