In the early 1940s a group of men met under the title of the Tube Alloys Consultative Council.

If that sounds dull, then that was the point.

In reality, the men were heading up one of the most ambitious British scientific efforts of all time.

The deliberately misleading name hid the fact the group were developing a nuclear weapon to use against the Nazis.

Nuclear fission – releasing massive amounts of energy from elements – had been discovered by German scientists Otto Hahn and Fritz Strassmann in the ’30s, prompting a race among nations to turn the discovery to their advantage.

Britain was slow out of the blocks, however. In 1939, scientists advised the government must secure supplies of uranium in Africa to stop them falling into German hands – but ministers dismissed the warnings.

It was judged the development of a nuclear bomb was unlikely, and one senior government scientist put the odds of one appearing at 100,000 to 1.

The threat was considered great enough to form a committee to investigate whether an atomic bomb would be possible, however.

The MAUD committee, named after physicist Niels Bohr’s housekeeper, Maud, was formed. It would later lead to the development of the Tube Alloys Consultative Committee.

Even at the top level of government, those with the highest level of security clearance would talk in whispered tones of obtaining and developing Tube Alloys, rather than refer to nuclear material. Eventually, Britain handed over much of its research to the US, who used it in the Manhattan Project, which developed the first nuclear bombs to be dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan.

Britain expected the US to hand over nuclear secrets which they had developed, but they were mistaken. Following the conclusion of the Second World War, the Americans decided to protect the technology, even after the Soviet Union developed its own bomb.

Even scientists like mathematician William Penney understood the loss of power Britain would experience if they fell too far behind the two Cold War powers. “The discriminative test for a first-class power is whether it has made an atomic bomb and we have either got to pass the test or suffer a serious loss of prestige both inside this country and internationally,” he said.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill, fearing Britain would lose even more prestige on the global stage following the end of the war, gave the go-ahead for a new nuclear project.

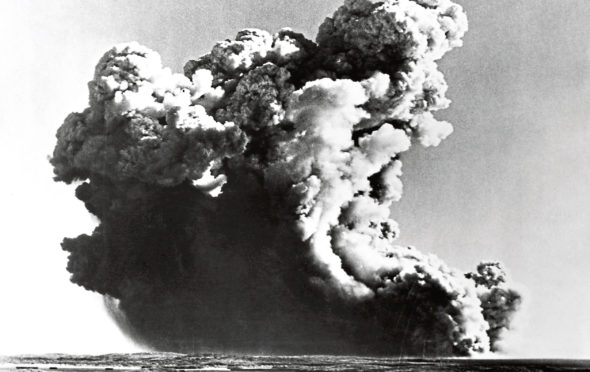

In five years, a device had been developed and, on October 3, 1952 was finally tested by the UK.

With permission of the Australian government, a nuclear bomb was placed on HMS Plym, a frigate at the Montebello islands, off north-west Australia.

One concern at the time was of Soviets smuggling a nuclear bomb and detonating it inside a port, so the bomb was placed inside the hull of the Plym.

The test, named Operation Hurricane, was successful, with a massive explosion leaving a 300-metre crater just off the island.

To Churchill’s delight, Britain had – for better or worse – finally become a nuclear power.

Enjoy the convenience of having The Sunday Post delivered as a digital ePaper straight to your smartphone, tablet or computer.

Subscribe for only £5.49 a month and enjoy all the benefits of the printed paper as a digital replica.

Subscribe